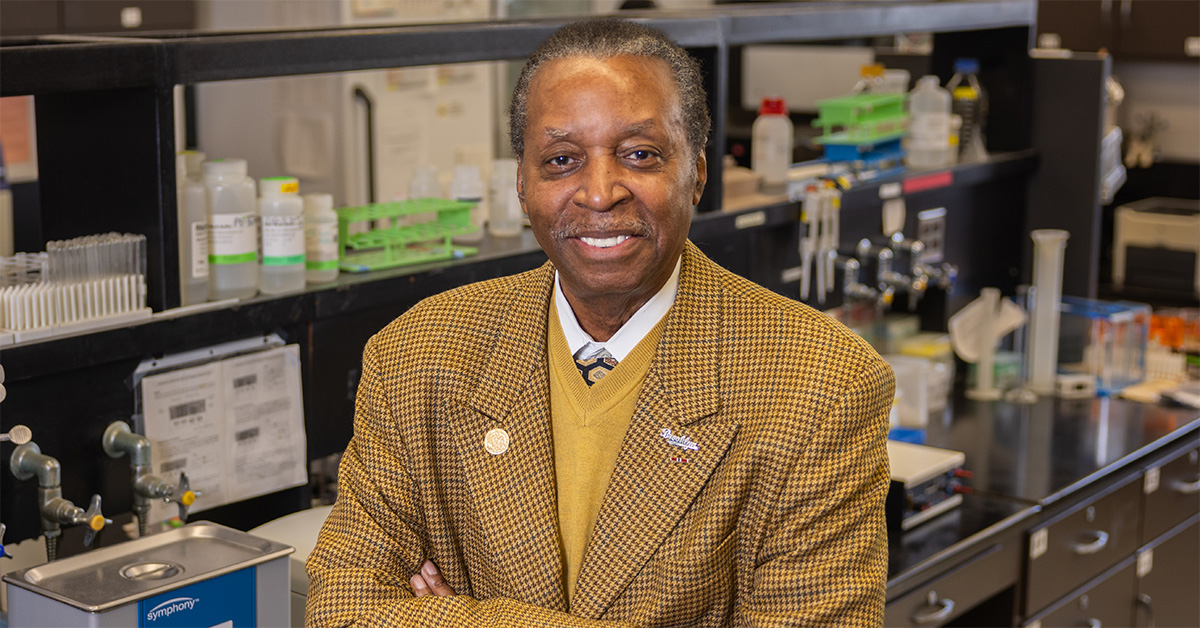

Dr. Lawrence Brown Jr. ’74, an addiction specialist and public health advocate, grew up in the Van Dyke Houses, Brownsville projects of Brooklyn, where he witnessed the consequences of addiction. After the Vietnam War, he decided to pursue a career in medicine. He graduated from Brooklyn College, NYU School of Medicine, and Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. This was followed by an internal medicine residency at Harlem Hospital and a fellowship in neuroendocrinology at Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. Dr. Brown has had a distinguished career, serving on the board of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, serving as the CEO of START Treatment and Recovery Centers in Brooklyn, and as a medical adviser to the NFL. Here, Dr. Brown, a clinical associate professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, discusses his journey from Brownsville to becoming a sought-after expert in addiction medicine and public health.

Why did you choose Brooklyn College?

My parents were second-generation New Yorkers whose parents made the Great Migration from the South in search of opportunities. My father was a truck driver. My mother—who is now 92—worked part-time at the post office and, at other times, as a director of a local community center. She was the guiding star of the family home. She wanted something different for her children—I am the oldest of four—than what she had. That is why I decided to go to college. I chose Brooklyn College because it was close to home and tuition was free—my parents could not provide financial support for me to attend college.

Can you tell us about your time at Brooklyn College?

There was a pause in my education. I was at Brooklyn College for one year and was on the cusp of deciding to take a leave of absence to pick up more hours at my part-time job—making my own money for the first time went a bit to my head—when Uncle Sam grabbed me. I was drafted and sent to Vietnam. After I finished my military service, which included receipt of a Bronze Star for merit, I came back to school. Before my senior year, I was fortunate to be admitted conditionally to NYU School of Medicine. The condition was that Brooklyn College would award my bachelor’s degree in mathematics if I completed the first year of medical school at NYU. That explains why when you look at my résumé, you will see that the time between Brooklyn College and NYU is only three years.

Addiction and public health are your specialties. How did you go from a math major to a medical doctor and addiction specialist?

I was motivated to be a physician to help my grandmother, who had heart disease and diabetes. In fact, I wanted to be a doctor from the age of 12. I knew that I had to take math and science, which I liked. I come from a neighborhood where addiction was prominent and still is. Unless there is going to be a change in this society, it will continue being a feature in the Brownsville community.

So, when it was time to choose a specialty in medical school, you decided on addiction medicine.

I thought I wanted to be a private practitioner and hang my shingle in Brownsville; I discovered the reality of health care in this country after my second year of medical school. I had also returned from Vietnam to see some of my friends in my neighborhood addicted or dead from drugs. I wanted to focus on what I call macroscopic issues of community rather than microscopic ones of individual patients. So, I attended Columbia for a master’s in public health. Public health is more than giving a prescription or an injection: it is about discovering the underlying reasons why patients in your community continue to suffer disproportionately excess morbidity and mortality. When I went to Harlem Hospital for my residency, I saw more folks who looked like me engaged in providing health care and addressing these unmet health care needs.

You are the medical adviser for the National Football League (NFL).

I have been since 1990. I was conducting clinical and behavioral health research on the relationship between addiction and HIV for the Addiction Research and Treatment Corporation, a nonprofit organization in Brooklyn that provides comprehensive services for substance use disorders and concurrent mental health and medical disorders, including HIV and hepatitis. The NFL approached me to provide oversight of their policies and programs to reduce substance use. While this relationship has evolved over the decades, initially I served as a medical adviser overseeing clinical care, drug testing, and the league’s prescription drug program. This consultancy led to a role during the 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics as volunteer, and because of my expertise in addiction medicine, ultimately as a board member of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, the national anti-doping organization in the United States for Olympic, Paralympic, Pan American, and Parapan American sport.

Tell us what you consider some of your more significant research.

One was increasing the knowledge of the relationships between HIV transmission and addiction via drug injection and/or unsafe sexual behaviors. Second was demonstrating the efficacy of interventions in preventing transmission or treating infected patients. Another is when the NFL asked me to assist the league in developing its HIV testing policy. In that case, I reached out to the CDC, with the permission of the NFL, to conduct studies of the prevalence of bleeding injuries to estimate the risk of contracting HIV through these types of injuries. We conducted a two-year study with physicians standing on the sidelines, capturing bleeding injuries. The conclusion, published in peer-reviewed journals, was that the risks were quite remote.

What advice would you give students today on choosing their field and following through?

I would focus on three areas. One is to choose a path that you enjoy. Secondly, build relationships and do what you can to maintain them, no matter what field you choose. What you know is important, but who you know is equally important. Finally, ask yourself if you are enhancing the lives of persons and communities who are underserved. If not, are you paying forward the sacrifices made by others on your behalf? At the end of the day, can it be said that you provided value and not just to those who you love or who love you, but for the greater good of those who are suffering?