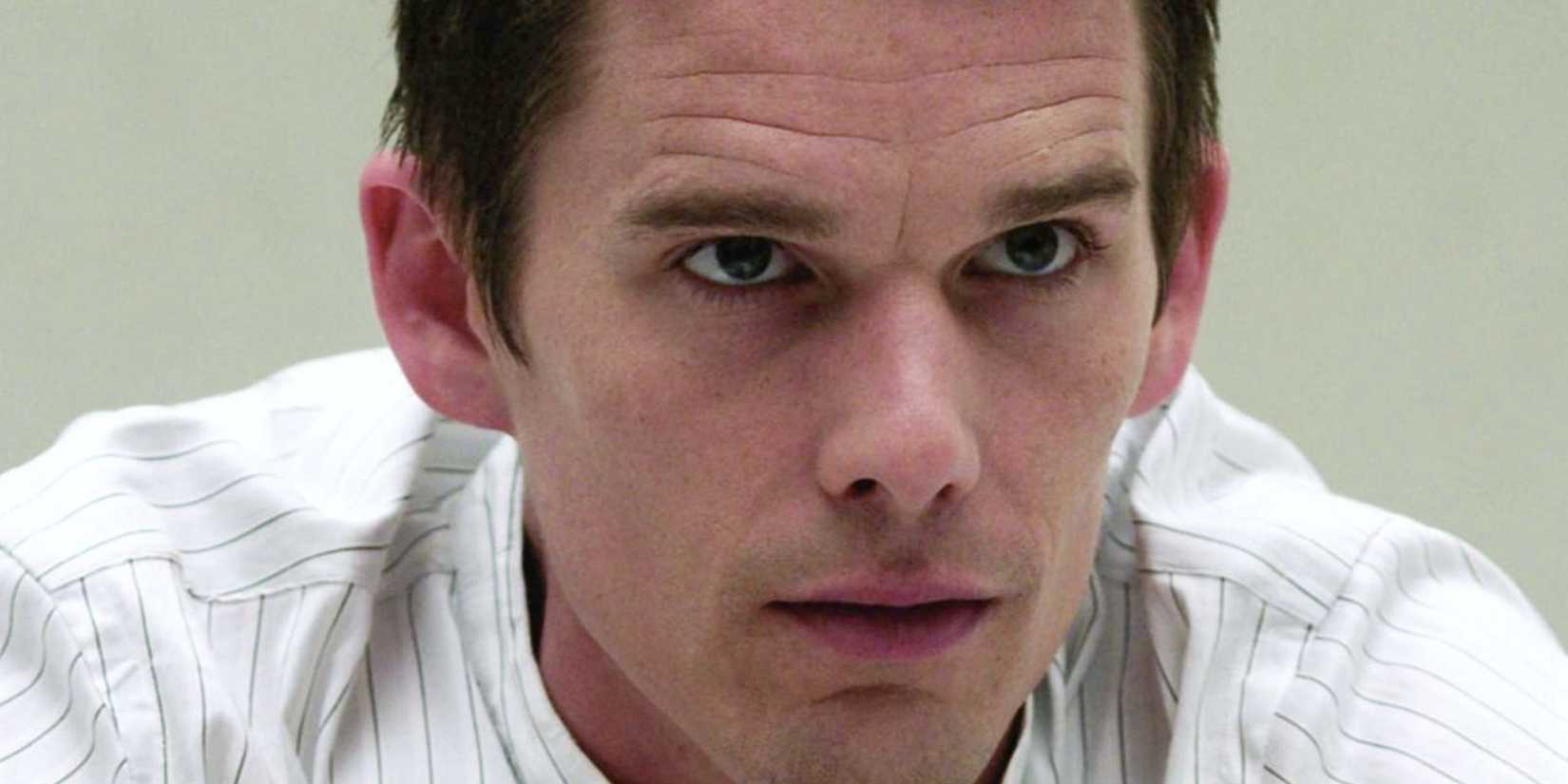

Ethan Hawke isn’t often the first name spoken in horror conversations, but maybe it’s time he should be. Across multiple decades, Hawke has built a genre resume defined by empathy rather than excess, crafting characters whose quiet humanity makes the horror around them hit harder. He’s not a franchise mascot. He’s not a slasher with a catchphrase. He doesn’t chew scenery or rely on gore to make himself unforgettable. Hawke is horror’s whisper in the dark — soft, steady, and inescapable. That quality sets him apart from the genre’s most obvious “Scream Kings.” Where someone like Bruce Campbell leans into bombastic physicality or Tony Todd commanded terror through presence and voice, Hawke gets under your skin by being disarmingly normal. His face, his cadence, his steady stillness make him feel safe, until they don’t.

And the truth is, he’s been doing it for a long time. Before Sinister, The Purge, or The Black Phone, Hawke gave audiences a glimpse of his horror instincts in Taking Lives. His ability to play trustworthy, even tender, while hiding something rotten underneath would become a defining signature. In Daybreakers, Sinister, The Purge, The Black Phone, and yes, Taking Lives, Hawke has mastered the horror of duality — using his natural warmth and introspection to make goodness feel fragile, and evil feel deeply personal. Hawke doesn’t just show up in horror — he elevates it. His performances turn fear into a character study, exploring terror not as an external threat but as something buried deep in human contradiction. If horror royalty is earned, not given, then Hawke’s crown is already waiting.

Ethan Hawke Perfectly Embodies the Reluctant Hero

What sets Hawke apart from most of his genre peers is how grounded his performances are, especially as the protagonist. He doesn’t perform fear as something theatrical, he lets it corrode him from the inside out. That interiority gives his horror work an uncommon emotional weight, especially in films that live and die on atmosphere. Take Sinister, one of the most enduring and terrifying studio horror films of the 2010s. Hawke’s portrayal of Ellison Oswalt — a washed-up true-crime writer who moves his family into a house where a brutal massacre took place — isn’t built on jump scares or bravado. Instead, it’s built on his unraveling. He drinks too much. He ignores the warning signs. He stares too long at cursed home movies. Hawke plays him like a man whose curiosity eats him alive. What’s terrifying isn’t Bagul’s home movies alone, it’s the way Ellison watches them, his face flickering with panic, obsession, and denial.

That same fragile humanity runs through The Purge, where Hawke plays James Sandin, a wealthy suburban husband profiting from the annual night of state-sanctioned violence. When that violence reaches his doorstep, his composure fractures fast, but Hawke doesn’t need a monologue or a breakdown — it’s communicated even in his silence. There’s a moment when he realizes the security systems he sells to others won’t save his own family, and you can feel the air leave the room. Both performances show Hawke’s rare ability to make terror deeply personal. He isn’t the traditional “tough guy” protagonist or the detached cynic. His fear is messy and lived-in, the kind that mirrors how real people react to unthinkable circumstances. And crucially, that emotional authenticity is the same thing that makes him so effective as a villain later on. His softness is the perfect camouflage.

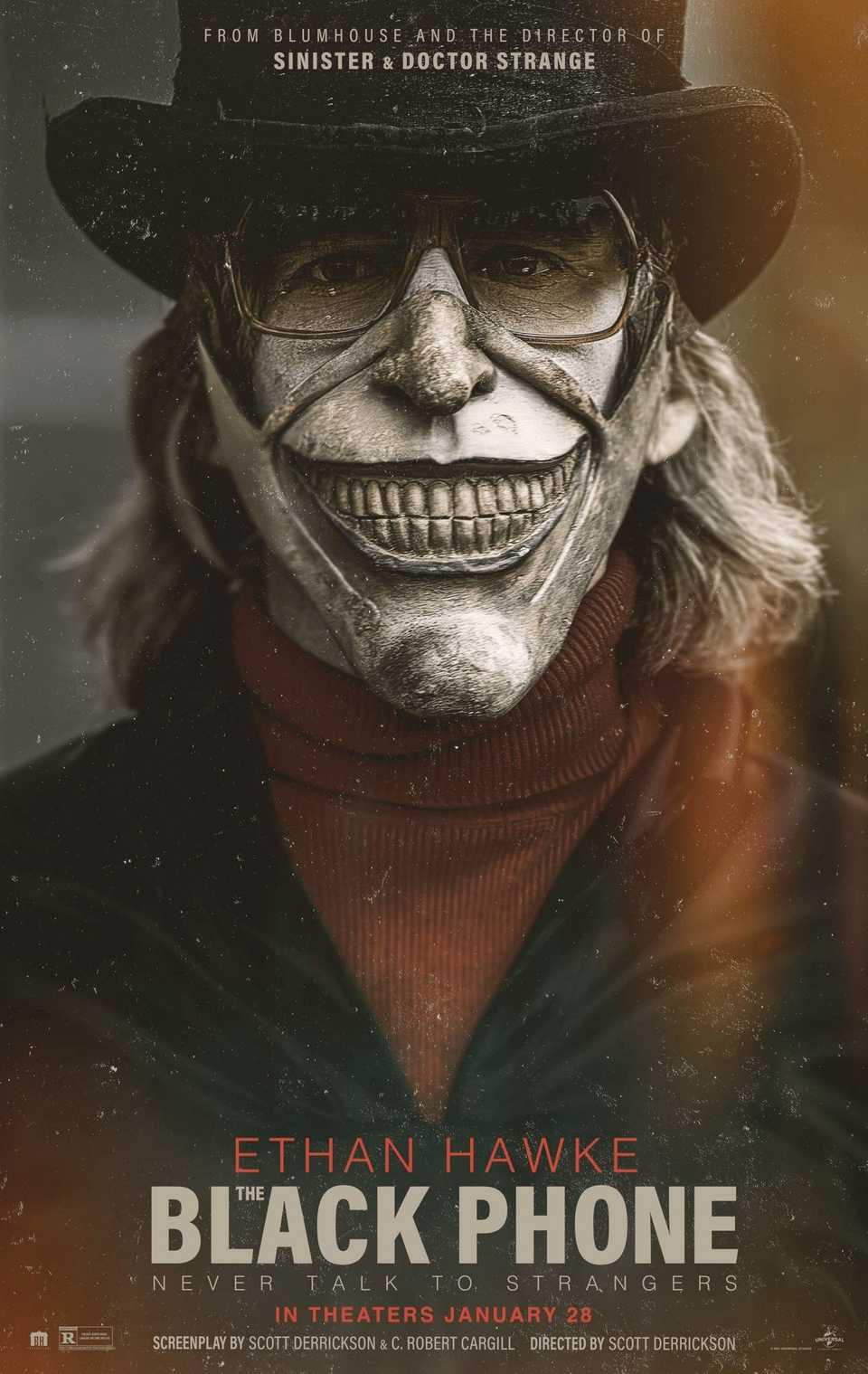

Hawke Transforms Warmth Into Terror

Taking Lives is the key that unlocks Hawke’s entire horror legacy within his career. In that 2004 thriller, he spends most of the film playing Paul, a mild-mannered art dealer who seems both vulnerable and kind — the ideal red herring. But what makes the reveal work isn’t shock value alone, it’s how convincing he is up until that point. Hawke doesn’t wink at the audience. He plays Paul with the same sincerity he gives to his heroic characters. When the twist lands, it feels like a betrayal. That quiet, open face, that gentle cadence — suddenly they’re loaded weapons. You feel tricked not by the movie, but by him. And that’s exactly what he does again, almost two decades later, in The Black Phone.

The Grabber isn’t a loud, theatrical slasher. Hawke uses the same tools that once made him the trustworthy lead and sharpens them into something dangerous, which he continues to do in the sequel, Black Phone 2. The way he tilts his head, the measured pauses between words, the almost parental tone of voice that makes every line land like a trap. Even when half his face is hidden behind those segmented masks, he communicates with microscopic control. This is Hawke’s real horror superpower: precision. He doesn’t rely on big, operatic villainy. He unsettles through smallness. Taking Lives showed he could make an audience trust him. The Black Phone proved he could make that trust feel like a trap.

A Vampire With a Conscience

Ethan Hawke holding a crossbow in ‘Daybreakers’Image via Lionsgate

Hawke’s horror legacy isn’t just built on villainy or victimhood. Daybreakers proves how easily he can anchor genre spectacle with quiet conviction. Released in 2009, the film imagines a future where vampires have overrun humanity, and blood — their only food source — is running out. Hawke plays Edward Dalton, a vampire scientist trying to find a cure. Where many vampire films lean into power or sensuality, Hawke goes small. Edward is exhausted, disillusioned, clinging to a moral compass that’s slipping through his fingers. He’s not a suave bloodsucker or a tragic gothic figure, he’s a man reckoning with the consequences of a seemingly irreversible world. That weary gravity gives the film an emotional backbone it wouldn’t otherwise have.

Hawke’s performance also sets Daybreakers apart in a genre crowded with archetypes. Vampires are often metaphors for excess, immortality, or hunger. Edward represents something else: guilt. The kind of guilt that lingers when humanity is long gone, but your conscience isn’t. And because Hawke doesn’t overplay it, the tragedy hits harder. It also fits beautifully into the larger arc of his horror career. In Taking Lives, he weaponizes empathy. In The Black Phone, he twists it into something monstrous. In Daybreakers, he wields it to humanize the inhuman. That range isn’t just impressive — it’s a rare elevating factor in the genre from one performer.

A Crown Earned in Silence

Ethan Hawke as the Grabber in The Black PhoneImage Via Universal Pictures

Hawke’s impact on horror isn’t loud, and that’s exactly what makes it so powerful. He doesn’t rely on excess to make himself memorable. He uses contrast, precision, and emotional honesty. He can embody the fragile center of a story — the man who breaks under the weight of fear — or become the darkness that tears it apart. From Taking Lives to The Black Phone, his performances have mapped out a career-long study in trust, betrayal, and the thin line between the two.

Hawke is often heralded for being an actor’s actor, as much as he is for being a performer who thrives in quiet spaces and finds meaning in the pauses. Horror is rarely associated with that kind of subtlety, but he’s carved a corner of the genre that belongs entirely to him. He doesn’t need a chainsaw, a mask, or a catchphrase to make himself unforgettable. He just needs a trembling voice, a quiet stare, and a heartbeat that doesn’t sound quite right. Horror royalty doesn’t need to wait for coronations — Hawke has already crowned himself through decades of genre-defining work.

Release Date

June 24, 2022

Runtime

102 minutes

Director

Scott Derrickson

Writers

C. Robert Cargill, Scott Derrickson