A new exhibit at the New York Historical, “The Recordings: Voices from the ‘Shoah’ Tapes,” begins with a statement from Louise Mirrer, the Manhattan museum’s president and CEO.

“It has become a commonplace to lament the rise of antisemitism in the United States,” it reads. Unlike other efforts to combat “the most recent iterations of this ancient scourge,” the new exhibit “takes a different, and in many respects more visceral approach: making audible antisemitism’s history and manifestation in communities during the Holocaust.”

The exhibit features recordings made by and for filmmaker Claude Lanzmann in the 1970s as he prepared what would become his monumental 1985 documentary “Shoah.” Mirrer’s remarks frame the exhibition in the aftermath of Oct. 7, emphasizing the urgent duty to preserve Holocaust memory and teach its lessons today. How audiences understand and apply those lessons is far from settled.

None of the 152 recordings on which this exhibition is based — interviews with survivors, perpetrators and bystanders — appeared in the final film, a nine-and-half hour epic that Roger Ebert described as a “550-minute howl of pain and anger in the face of genocide.” Devoid of archival material and built of patient interviews with often wary witnesses to the Holocaust in Poland, it elevated survivor testimonies as primary historical sources. Both the Fortunoff Video Archive at Yale and Stephen Spielberg’s (now USC’s) Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive were shaped by its ethos.

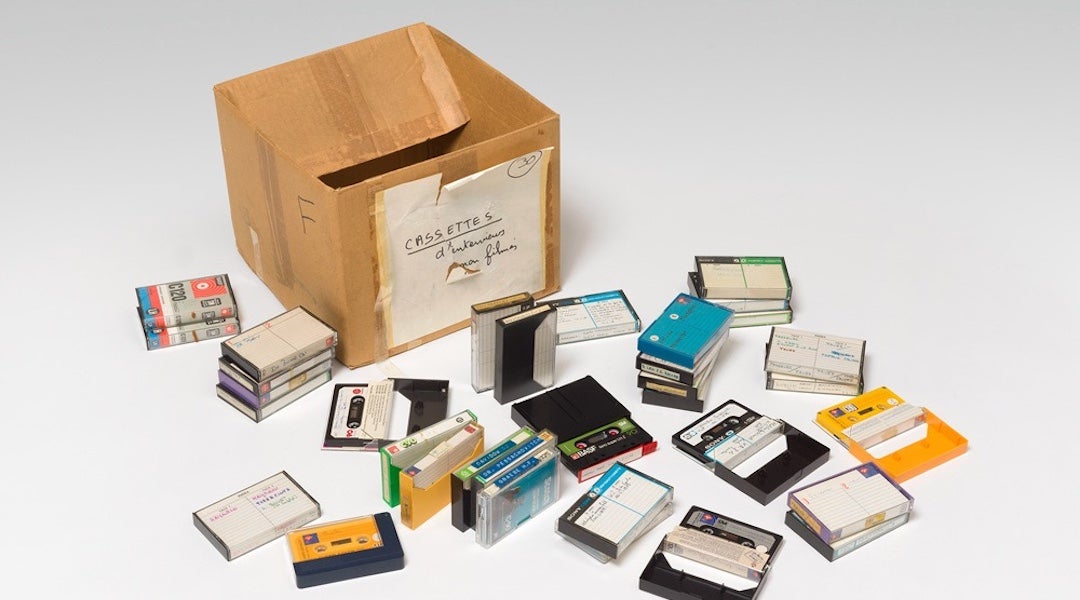

After Lanzmann’s death in 2018, the tapes of the unused interviews were transferred to the Jewish Museum Berlin and added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. In a rare cross-Atlantic collaboration, they are being made public for the first time, with exhibitions opening simultaneously in Berlin and New York.

“This is a very unusual exhibition — almost exclusively audio,” said Mirrer at a press showing this week, a few days after the exhibit opened. “We are at the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the 40th anniversary of ‘Shoah,’ and what would have been Claude Lanzmann’s 100th birthday. With rising antisemitism in our city, our nation and our world, the occasion demands that we rethink how we confront hate in the present. Listening to these tapes makes clear that history can, in fact, repeat itself.”

Keren Ben-Horin, a curatorial scholar in women’s history and a co-curator of the show, described the exhibition as “new wine” poured into the vessel of Lanzmann’s legacy. The tapes, she noted, capture a filmmaker still struggling to figure out how to tell a story that was, for many just three decades removed from the genocide, still too raw to revisit.

“The Recordings: Voices from the Shoah Tapes,” on view at the New York Historical, features listening stations where visitors can hear the testimony of Holocaust survivors, perpetrators and resisters, including Hillel Kook (Peter Bergson), seen in the video talking about his efforts to influence U.S. government officials to save Europe’s Jews. (JTA photo)

“In the mid-1970s, Lanzmann was grappling with questions historians always face: Where does this story begin?” she said. “With the Nazi rise to power? The 19th century? Biblical times?”

The recordings show him pursuing leads in all directions — the Vatican, American Jewish groups, Lithuania — many of which were abandoned as he shone the film’s ultimate focus on the genocide in Poland.

By the late 1970s, Lanzmann was visiting Nazi killing sites in Poland for the first time, an experience that shook him. (One recording features Lanzmann’s halting, shocked reactions during a visit to a concentration camp.) Ben-Horin described how the physical spaces, and the contemporary silences surrounding them, shaped Lanzmann’s sense of the “mechanics of extermination”: the trains, the bureaucrats, the bystanders.

He devoted 11 years to editing 350 hours of raw interviews — losing the original Israeli backers at Yad Vashem who, impatient after two years with no finished film, withdrew support.

What was unusual then, and still startling now, was Lanzmann’s insistence on speaking not only with survivors but also perpetrators and collaborators. Some of the recordings capture the moment when former camp guards and nurses slammed doors in the faces of his researchers. Others offered evasions. A few spoke only when Lanzmann, flouting the ethics of journalism but committed to the project of memory, recorded them covertly.

“He felt he had to put certain ethics aside in order to ensure the story was told,” Ben-Horin said.

If “Shoah” was known for its refusal to use archival footage, the New York Historical exhibition extends that discipline. “It’s a listening experience,” said Valerie Paley, senior vice president and director of the museum’s Patricia D. Klingenstein Library. “We wanted to create a space where one has to quiet one’s noise and lean in.”

The spare gallery, designed by director of exhibitions Gerhard Schlansky, features listening stations with headphones and video monitors. Visitors sit in front of the monitors, hearing voices in their original languages, paired with English translations. At one station, the famed Yiddish poet Avrom Sutskever struggles to describe the horrors he witnessed in the Vilna Ghetto; at another, Hillel Kook, the Zionist activist who went under the nom de résistance Peter Bergson, talks about his futile efforts to rouse the U.S. State Department about the extermination.

The interviews were recorded in Poland, Lithuania, Israel, the United States — places where survivors resettled and memories followed. “You get such a sense of the scope — the distances [Lanzmann] traveled, the lengths he went to tell the story,” Ben-Horin said.

In 1979, Claude Lanzmann (right) interviews Tadeusz Pankiewicz, a Polish pharmacist who aided Jews in the Krakow ghetto, for the film “Shoah.” (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

The question of place also hangs over the exhibit: What makes it right for the New York Historical, until recently known as the New-York Historical Society?

Mirrer said the museum’s mission is to tell “American history through the lens of New York.”

“Our institution tells the story of a nation built by immigrants — many of whom came because they could no longer live in their homelands,” she said. “This city was the beneficiary of people fleeing religious oppression, persecution, and other forms of hate.”

That connection is made clear in another exhibit that also opened on Nov. 28, “Stirring the Melting Pot,” which features photographs of the city’s immigrant experience. The Shoah exhibit in fact flows into the immigration exhibit.

“Together, the shows reflect the horrors of one homeland and the sanctuary of another,” said Mirrer.

Holocaust exhibits, though, are rarely just about history. The way we teach and learn about the Holocaust has been the subject of a recent dustup over remarks by the author Sarah Hurwitz — a fractal of a broader debate over whether Holocaust education should engage with the war in Gaza, genocides that take place around the world or other injustices.

The “Shoah” exhibit doesn’t try to answer that question. Instead, the museum positions both exhibits as part of next year’s commemoration of America’s 250th birthday, and the hot-button issue of what democracy means — and what threatens it.

“Democracy is the antithesis of what you listen to in these listening stations,” said Mirrer. “And that is why so many people, including the people who were interviewed here, end up in Florida and California and New York City.

“But you know, there is a clear and present challenge right now to Jewish people and many other people, for those very same reasons that those people fled their homelands. We are seeing those challenges here in our city and in our nation. It’s not our job to tell people what to think, but it’s our job to help them understand and as a result, to really have guidance on how to act in a democracy.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NYJW or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.