Warshaw says 18-year incumbent Tom DiNapoli — who has never faced a primary election opponent — has done a poor job managing the state’s $291 billion pension fund.

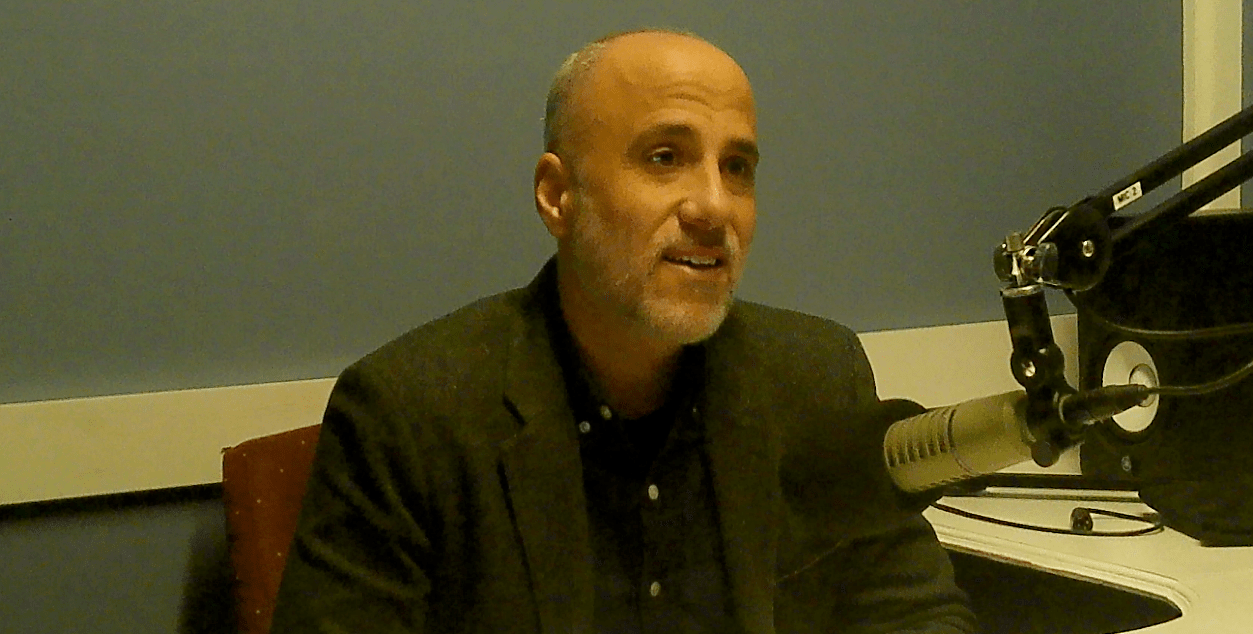

Drew Warshaw, candidate for New York State comptroller.

New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli has been the state’s chief financial officer for 18 years.

That’s long enough, according to Drew Warshaw, who hopes to compete the first contested primary election DiNapoli has faced in his long tenure.

It’s “one of the most powerful offices in government,” Warshaw said in an interview with Investigative Post this week. And yet “virtually no one has ever heard” of it, many “can barely pronounce” it, and even fewer could name the man who’d held the office since 2007.

The office’s power, Warshaw said, derives from its stewardship of the state’s $291 billion pension fund and its oversight of “anything that touches the state tax dollar.”

DiNapoli has failed to exercise the office’s potential in both areas, he said, and those failures hit New Yorkers squarely in the wallet.

Warshaw has three major criticisms of DiNapoli’s performance:

He says DiNapoli has done a poor job overseeing the state’s pension fund, significantly underperforming the market while paying $12 billion in fees to Wall Street money managers.

He faults the comptroller’s office for its failure to return unclaimed funds to New Yorkers. That pot of unreturned money has grown from $7 billion to $20 billion since DiNapoli took office, though there’s only $100 million on hand to pay out claims. The rest has been swept into the state’s general fund to help balance budgets.

He argues the comptroller’s office should use its audit powers in ways that will more directly save taxpayers money — for example, scrutinizing the Public Service Commission’s oversight of utility rates.

“He’s sitting on all this power and all this money, and the affordability crisis is getting worse and worse and worse, and we can actually do something about it,” Warshaw said.

DiNapoli, a Long Islander, has been in public service his entire adult life.

He was elected to his local school board at age 18 and worked as a legislative staffer in the Assembly and in Congress. He served 20 years in the Assembly until 2007, when his colleagues in the state Legislature appointed him to succeed Alan Hevesi, who was forced to resign the comptroller’s office and later sentenced to jail on corruption charges.

Since then, DiNapoli has been returned to office four times without significant opposition. Warshaw declared his intention to break that streak in May and in July announced his campaign had raised just over $1 million.

As of its most recent disclosure filing in July, DiNapoli campaign committee had less money in the bank than Warshaw — just over $600,000 — but he’ll have no problem raising more. He has all the advantages of an incumbent.

Warshaw’s public-private pedigree

Warshaw, 44, graduated from Cornell University, where he co-founded a student organization called Democracy Matters, which lobbied for campaign finance reform in Albany. He joined Eliot Spitzer’s 2006 campaign for governor and served as deputy chief of staff in that scandal-abbreviated administration.

After Spitzer’s resignation in 2008, Warshaw spent four years with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, working on the reconstruction of the World Trade Center — a project he said exposed him to “peak government dysfunction, with agencies battling for turf, and private developers, insurance companies and the whole thing.”

He earned an MBA at Columbia University, then spent eight years working for a company that built solar farms around the country. From there he joined Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit affordable housing developer. He worked there until May, when he quit to run for state comptroller.

Warshaw said Enterprise “raised and deployed $2 billion every year,” but the company was barely making a dent in the shortage of quality, low-cost homes.

“The bottom line was, we were losing. The affordability crisis was getting worse,” he said.

He decided to run for comptroller, he said, so that instead of lobbying officials “to be faster, smarter, cheaper, better,” he could work the levers of government himself.

“I truly believe the cavalry is us,” Warshaw said. “I don’t think anyone else is coming. I think it takes people like us, individual humans, getting into positions of power that control power and money and then using it for people without it.”

The underperforming pension fund

New York State’s pension fund is “the third largest pool of public capital” in the country, Warshaw said, funded by contributions from municipalities and their employees across the state.

The state comptroller is steward of the $291 billion fund and its investments. Warshaw contends DiNapoli has done a poor job, underperforming the market while paying billions in fees to Wall Street brokers.

“We compared him to his own benchmarks,” Warshaw said, referring to the annual fund reports the comptroller’s office issues. “And it turns out he’s underperformed his own benchmarks by 39 percent.”

Warshaw said that underperformance has resulted in higher local taxes. State law requires that the pension fund be fully funded. If the returns on the fund’s investments don’t achieve that, local governments and their workers must make up the difference.

His analysis also found that DiNapoli’s office paid $12 billion in fees to nearly 700 outside investment managers “to try to beat the market,” which he said seldom pans out over the long term. Taxpayers would be better served if the money were parked in low-cost index funds.

“We’re not going to try and get greedy and beat the market and light taxpayer money on fire anymore. We’re going to take the market return and we’re going to focus the resources of the office on a million other things to lower costs for New Yorkers.”

For example, he said, he’d like to leverage the pension fund to lower the cost of housing.

Currently, Warshaw said, the pension fund has $30 billion in real estate investments. He’d like to direct $10 billion of that into an affordable housing fund.

“We invest that in homes that New Yorkers can actually afford — here in Buffalo, in New York City, across Long Island, in central New York and Albany,” he said.

“And everyone across the country is going to go, ‘What are they doing in New York? I didn’t realize we could do that.’ And they’re going to start doing the same thing. We’re going to unlock billions of dollars to address the biggest domestic policy crisis that we have right now.”

Returning New Yorkers’ unclaimed funds

Another of the comptroller’s duties is finding the rightful owners of unclaimed funds — inheritances, tax and fee refunds, lawsuit settlements, etc. — and sending them their money.

Here, too, Warshaw said, the incumbent’s record is poor. When DiNapoli took office in 2007, the state held $7 billion in unclaimed funds. That number now stands at $20 billion.

In fact, the comptroller’s office holds just $100 million to pay legitimate claims for lost money. Each year, the rest has been swept into that state’s general fund to help balance budgets.

But that $20 billion remains a debt on paper, Warshaw said, and there’s no statute of limitations on claims against it.

“It’s not his money, it’s not the state’s money, it’s New Yorkers’ money,” he said. “He’s taken our money, and instead of giving it back to us, which is in his job description, he’s turned it over to the state to spend it on who knows what.”

DiNapoli’s office has said most of the money is unreturnable, because the legitimate claimants are dead or impossible to find. Warshaw waved off those excuses.

“They know your name, they know how much you’re owed. They know your last known address. They have access to all this publicly available data, and they have this thing here in 2025 called AI,” he said.

Expanding the scope of audits

Warshaw allowed that DiNapoli’s auditors do yeoman’s work watchdogging public finances, from the smallest lighting district to the biggest municipal governments in the state. The comptroller’s office issues hundreds of audits every year and tracks municipalities’ susceptibility to fiscal stress.

Still, he said he thinks there’s more to be done with the comptroller’s oversight power. He said he’d like to audit the state’s Public Service Commission, which has a history of approving utility companies’ requests to increase electricity and gas rates — sometimes by double digits. Rochester Gas and Electric recently proposed a 36 percent rate hike, for example, which Warshaw described as “an admission of failure.”

Similarly, he’d like to audit the state’s Department of Financial Services, which regulates the insurance industry.

“And how are they doing? We have no idea,” he said. “We are going to audit them, and we’re going to understand why it seems to be the business model of insurance companies to take your premiums but to never pay them out.”

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletters

Two other Democrats have followed Warsaw into the comptroller’s race in recent months. Raj Goyle is a former Kansas state legislator who ran for Congress there in 2010 and now lives in Manhattan. Adem Bunkeddeko is a two-time congressional candidate from Brooklyn.

A crowded primary ballot favors the incumbent, but Warshaw said he prefers to see the influx of candidates as proof there’s an appetite for change in Albany.

“When someone is treating a job like a lifetime appointment, when they’ve been there for 18 years, I think it is a good thing when other New Yorkers stand up and say, ‘We could do better,’” he said.

“Hopefully, I am the preferred alternative.”

This Friday, Investigative Post interviews Mayor-elect Sean Ryan at the Burchfield Penney Art Center at 7 p.m. Be there!

posted 32 minutes ago – December 10, 2025