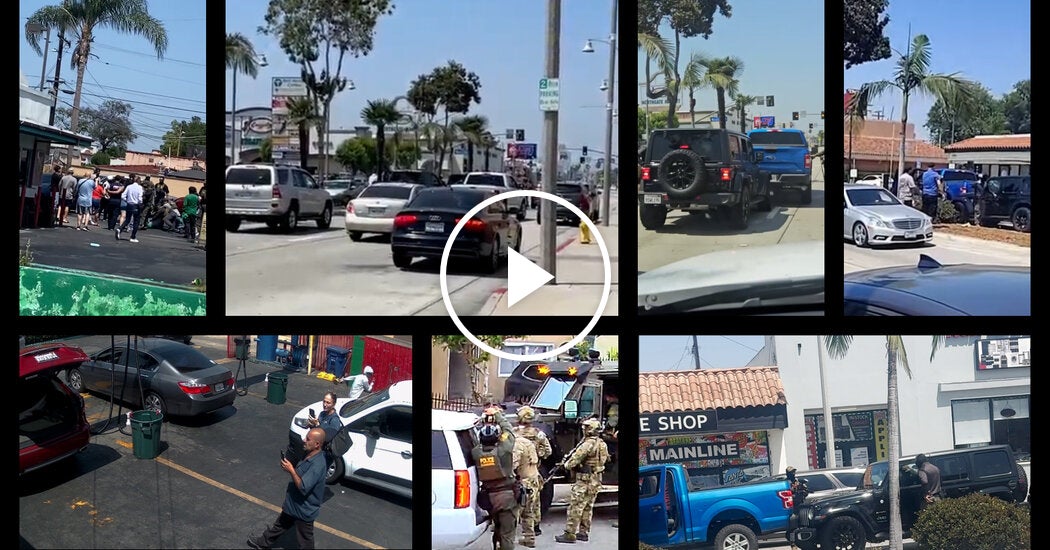

It’s just after 6 a.m. on Flower Street. Amid the morning calm, a security camera captures a SWAT team moving in formation. Operators in tactical gear carry ladders into the backyard. Another group enters the front and attaches strips of explosives along the windows and door. Inside, Jenny Ramirez and her two kids are sleeping when her phone rings. It’s a neighbor calling. “Jenny, Jenny, Jenny, wake up, wake up. I see a lot of police in front of your house. Are you OK? Get up.” Out front an armored vehicle pulls up. It’s carrying a K-9 team, a photographer and a drone operator. At the end of the convoy is a U.S. Border Patrol vehicle. These are federal immigration agents at the home of U.S. citizens And they’re ordering them to exit immediately. Agents wait 14 seconds, then blow out the bedroom window. “My 6-year-old started screaming, ‘We’re here, we’re here, we’re OK, we’re OK.’ But he wasn’t understanding. It wasn’t, like, something that happened to the house and they were coming to help us. I told him, ‘They’re not helping us.’” The second explosion blows off the front door. We wanted to understand what prompted this show of force and use of manpower. These high-risk tactics, according to current and former federal officials, are typically used for drug smugglers and violent fugitives, not by immigration agents trying to arrest a U.S. citizen accused of “injuring government property.” Who it turns out isn’t even home. But a closer look at the footage shows the man behind this raid is on scene watching. This is Greg Bovino. ♫ “Allow me to reintroduce myself. My name is — ” ♫ He’s the Border Patrol chief who’s become a key figure and social media fixture in the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown and slick video campaign. Bovino’s rolled out cavalry in Los Angeles, boat patrols in Chicago, strip mall sweeps in Charlotte. Injecting Border Patrol tactics into areas nowhere near the border and sending agents trained to patrol vast deserts for border crossers into busy urban communities to round up unprecedented numbers of potential deportees. “This is how and why we secure the homeland.” Bovino’s playbook is a stark departure from ICE, a separate arm of Homeland Security that’s historically conducted more methodical, time-consuming investigations of individual targets. “On behalf of the men and women of the United States Border Patrol, it’s time to turn and burn. We’re turning and burning onto that next target.” “Turn-and-burn” isn’t showboating, Bovino says, it’s using fast-moving shows of force to deter criminals and keep agents from getting bogged down by agitators so they can enforce laws that he says have been neglected for decades. “We’re here and we’re not going anywhere.” The messaging from the administration has been clear. Bovino and his aggressive approach are delivering the deportations President Trump promised and keeping Americans safe. But we took a deeper look at one of the operations featured on Bovino’s timeline. This raid on Flower Street and the events that led up to it, syncing hours of video and audio from CCTV, social media and a trove of never-before-seen police body cameras. We found behind Bovino’s social media hype about law and order lies an entirely different story about his turn-and-burn playbook and the spiral of consequences that it unleashes. The backstory of the raid at Jenny Ramirez’s house began a week earlier. An immigration operation at two nearby car washes that seized a handful of potential deportees. But it also led to four vehicle crashes, hours of protests and violent clashes with federal agents, and emergency responses by six local police forces. “Can you get us additional units from East L.A., please?” “We got to get this crowd out of here.” By day’s end, four U.S. citizens with no prior records of violence were facing allegations of federal felonies. “I just feel like they’re trying to frame me as a criminal.” “If you jump in front of a vehicle —” “I was never charged. I was never read my rights.” “We’re U.S. citizens.” “I felt like we were in the wrong place at the wrong time.” On June 20th, across the heavily Latino suburbs southeast of Los Angeles, reports of immigration agents and angry backlash were becoming a routine part of daily life. “Are these [expletive] guys for one man? So crazy. Be [expletive] ashamed of yourselves.” “What’s your badge number actually?” “He’s got 45, 30.” “Leave him alone, [expletive]. Leave him alone.” Among the locations targeted was in the city of Bell, a local business here along the main drag, Jack’s Car Wash. It was like any other busy Friday afternoon until around 2:40 p.m., when footage shows seven seemingly ordinary vehicles begin to stream in. At least 16 people would emerge. “It’s a lot of people for the car wash.” One worker who didn’t want to be identified for fear of retribution told The Times he thought the cars pulling in wanted a wash. “I was like, Oh, it’s probably a customer. But when they came out, they had these vests and, like, ski masks and sunglasses on, so you couldn’t identify who it was.” Most are Border Patrol agents, and according to a memo obtained by The Times, they’ve come prepared for elevated security risks. Workers said agents seem to approach everyone as a suspect but ask just two questions. “He asked, ‘Are you a citizen? Are you from here?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘Oh, where were you born at?’ I said, ‘Bellflower, California.’ He left right away.” The agents clearly spark fear for one customer who runs into the drive-through. Then a worker dashes off in the opposite direction. Agents sprint after the runners as new ones arrive to assist and search for more suspects. Meanwhile, in the restaurant parking lot next to Jack’s are Jenny Ramirez and her partner, Jorge, who had just delivered an order for Uber Eats. They’re in their Jeep eating a quick lunch while the baby naps, she says, when they notice a man sitting in a parked SUV. “And I’m like, Maybe they’re just waiting like us for orders. And then when I just, like, saw what looked like a rifle, I told him, ‘Let’s go, let’s go, let’s go.’” When Jorge goes, he turns right, away from the car wash. But now his black Jeep is driving into a high-speed pursuit. This blue pickup is an unmarked Border Patrol vehicle chasing the fleeing car wash worker, who, according to this driver’s video, synchronized with CCTV footage, runs right in front of Jorge’s Jeep. “We were, like, so close to, like, running him over, and then we see this blue truck trying to ram us on my side. I just thought it was road rage at that point because the vehicles are not marked or anything.” But then the pickup suddenly stops to let an agent jump out. It gets rear-ended by Jorge’s Jeep. Immediately, masked agents emerge with weapons drawn. “They jumped out and they were going towards us and we didn’t even have anything to do with it. We were just trying to get away from that place.” Jorge tries to back away, but his bumper is hooked on to the pickup, and both vehicles surge backward, right into a gray vehicle behind them. “This guy is crazy. Meanwhile, about five minutes away in the neighboring town of Maywood, at Xpress Fleet Wash, another turn-and-burn operation is about to unfold. Driving nearby on his way to work is Edgardo Urias, a 19-year-old college student. His dash camera shows a blue SUV on his left, veering into his lane and cutting him off. “There’s no signal no anything, and I just thought, like, regular L.A. drivers.” But then the SUV suddenly stops in a busy lane of traffic, and the back door flies open. The impact sends Edgardo’s side mirror flying through his window. “What was that, bro? What the [expletive]?” No one in the SUV appears to acknowledge the collision. Two men in ballistic vests scramble out to the drying area. Other agents who hang back to dislodge their car door ignore Edgardo. “I see that this is, like, a suspected ICE raid. Like, I’m still not going to leave without an insurance because that could be, like, still to hit and run on me. And then I also have my car messed up.” For nearly two minutes, Edgardo, who seems free to leave, snaps photos and pleads for insurance. But then, after taking down a passerby who flees into traffic, agents abruptly turn their sights on Edgardo. “I’m just confused what’s going on.” “Why are they arresting me after they caused an accident?” Back at Jack’s car wash, a worker in green named Manuel is getting questioned and detained. “Leave them alone! They’re just working. They’re just working, bro.” Across the lot, a worker in white is looking on. Jose Cervantes Licia is a longtime employee of Jack’s who appears increasingly agitated watching the raid unfold. Suddenly, he charges toward the agent leading Manuel away. A scuffle breaks out. Then a silver pickup flies across oncoming traffic. “Oh, my god!” And rams into an unmarked federal vehicle. Manuel gets loose. Jose gets chased. Both get caught and cuffed. At the same time, up the street from Jack’s — “Hey, put the guns away” — Jenny and Jorge’s Jeep is still hooked to the pickup, and they’re sitting inside, terrified the masked agents are trying to take Jorge into custody. “‘Get out of the car, get out of the car.’ Trying to get George out, but they didn’t say who they were. They didn’t say why. We didn’t open the doors, because we were scared. “[Expletive] dogs, man, what the [expletive]?” One agent pulls out a baton. Another fires a pepper ball launcher. “Hey, put, they got a family. Put the guns away.” Agents say they’re trying to stop Jorge from fleeing, according to court documents, after what they allege was a deliberate collision to block their pursuit. Former agents told The Times a pursuit on busy city streets for a subject who posed no known threat wasn’t part of Border Patrol training during the previous administration. Most, however, broadly defended this shift to more aggressive enforcement policies, saying it was necessary after decades of lax border enforcement. And Jorge’s driving, according to some of the agents, posed a serious threat given the hostile operating environment. This isn’t the type of policing, or setting, they said, that Border Patrol agents typically handle. “There’s a [expletive] baby in the car, bro. Put the [expletive] guns away, dude.” At the other car wash in Maywood, no Xpress workers or customers are detained. Bovino’s turn-and-burn playbook appears to be backfiring. “Guys, don’t got nothing else to do, huh?” Once agents move Edgardo into their vehicle, it appears they’re planning to leave. But apparently, there’s uncertainty about what to do with him, according to audio from his dash camera. Instead of getting on the road, agents sit in this Tahoe with Edgardo in front of the car wash for nearly an hour. It’s not clear what they’re waiting for, but Edgardo says agents are making calls requesting help from local law enforcement as the crowd grows and tensions rise. “They’re saying that this would have never happened if, like, I would have just, like, been on my way, but I was being on my way. I was just trying to go to work.” “Yo, what’s your name? Brother, what’s your name?” What’s your name?” Over in Bell, federal backup is flooding in, but none of the heavily armed masked agents can defuse the situation or detach the pickup from Jorge and Jenny’s Jeep. Within minutes, Bell police arrive, wearing body cameras that give a rare behind-the-scenes look at how turn-and-burn tactics escalate a minor accident. And unleash mayhem for local officers who are barred from assisting federal immigration operations but sworn to uphold public safety. “Sir, do you guys need paramedics?” Initially, officers try to handle the collision like any other. “Can you tell me what happened?” The Border Patrol agent says the opposite. The Jeep, he says, cut him off. The agent also alleges to police that Jorge might be a repeat offender. “OK.” Federal agents tread lightly, but their requests of local police quickly mount. And once officers get Jenny and Jorge to exit the Jeep — and a tow truck positioned to unhook the vehicles — “OK, you guys are good” — Jenny says they’re told they can go home. “I asked the Border Patrol, too, ‘Are we free to go?’ He said, ‘You guys are fine. Go.’” But no one’s going anywhere at this point because the show of force has not deterred but attracted hundreds of onlookers and protesters. And now agents need help getting out. The federal vehicles, they say, must all leave together to protect against attacks. That worst case scenario, it turns out, will unfold minutes later after many failed attempts to move the crowd. “Move out of the street so they can leave.” “Hey, can you guys clear the driveway so we can get them out of here?” “Can you just go to the side, please?” The moment that shifts the protests into violence comes when two new federal vehicles arrive. “Go! Hey, hey!” And accelerate toward the crowd. “They absolutely just tried to run some folks over.” Bystanders erupt at federal agents. “What are you doing? You’re [expletive] dumb!” And at local police. The sergeant in charge scrambles. “All right guys, hey, it’s time to clear out.” To clear an exit path and de-escalate the scene. “Come on, let them out of here, let them get out of here.” But it has the opposite effect. “Get out of here, come on, let them get out of here.” “What’s your badge number? What’s your badge number?” As the sergeant waves people to cross, this federal vehicle starts rolling toward them. A man bangs on the hood and immediately gets pinned to the ground. The takedown sets off new backlash and a hail of tear gas. “What the [expletive]?” “Oh, my God.” Local police caught up in the scuffle — “Watch out, we’re taking [expletive]” — call for emergency help. “Can you get us additional units from East L.A., please?” “Do you need any mutual aid? 999.” “You guys almost out of here?” “Yeah, two flat tires now, so I don’t know.” It was during these minutes of mayhem that federal agents made the one request that police officers denied. That is not what happened, according to Isaías Peña Salcedo. “This is where I was listening to the officer telling us to cross, and that’s when I — ” Isaías, a 25-year-old construction worker, said he hadn’t come to protest. He’d been headed to a nearby grocery store with his friend’s family and reluctantly agreed to see what was causing the commotion. When violence erupted, he says he was following orders to leave. “I was told by the officer to clear the path. And that’s when the car started rolling into me, and I was like, ‘Dude, what the heck?’” Not hard enough to put a dent or anything, but just, What are you doing, man? Like, I’m getting told to cross, like, can’t you see?” Being a citizen, he said, didn’t matter. I always carry my passport on me with everything going on. He took my passport, put it right back in my pocket, tossed me into the truck.” “Leave him alone — he’s a kid.” Before the federal convoys finally leave the scenes in Bell and in Maywood, federal agents deploy more tear gas into a nearby park and into streets filled with local police officers. Federal agents leaving the operations were frustrated, according to Isaías and Edgardo. “They were dropping off all the people they caught and they were mad because they’re like, ‘Oh, how much did we get today?’” “They were just saying that, like, they had one body and that was me, and then some other guys had two bodies.” “Three and they’re all U.S.C.s, like U.S. citizens.” At least one detainee was not a U.S. citizen. Co-workers said Manuel, the car wash employee in green, was deported to Mexico within days. D.H.S. did not respond to questions about the Jack’s customer who fled or the man detained near Xpress Car Wash. But the collateral damage was vast. “You had the traffic collision, you had the deployment of gas by the federal agents, vandalism against both the federal vehicles and against our vehicle.” Bell police faced days of protests and spent months investigating each act of vandalism. But the chief said his officers were caught off guard, not only by the federal operation, but also by their tactics. “Anytime you move crowds, whether you use less lethal weapons or gas, it has an effect in the surrounding area. It has an effect on the cops. It has an effect on the community. The federal government may have a certain way of handling crowd management, but we as an agency will not drive into crowds.” For each of the four U.S. citizens caught in the dragnet of the day, the fallout was different. For Jose Cervantes Licia, who declined interview requests, it led to home detention and felony charges of assault on a federal officer. The charges were later reduced to a misdemeanor, and Jose accepted a plea deal. Isaías says he spent almost three days locked up, not allowed to call a lawyer or even his family. “I was never charged. I was never read my rights. I wasn’t even allowed to see the judge. Yeah, OK, if I did this, take me. Don’t just grab me. That’s third-world country stuff.” He said he had no idea if or when he’d get out. “You’re just in there looking at the ceiling at the white paint. I thought I was gonna be in there for a couple years, so I was already mentally preparing myself.” After 64 hours, Isaías says he was told they were finally taking him to see a judge, but instead, with no explanation, he was released. “Like, it just messed up my head mentally, like, pretty bad.” “You’re impeding federal agents. You’re impeding federal agents. You will be arrested.” Edgardo was also never charged. He says during intake he managed to show videos of the collision on his phone to a federal investigator. “He sent it to his boss. He’s just, like, ’Wow.’ He was just, like, apologizing on behalf of the ICE and Border Patrol because they never did, so.” Greg Bovino, the Border Patrol chief, did not respond to our interview request or to specific questions about the tactics used in these operations. Spokespeople with Homeland Security and Customs and Border Protection provided a written response, which in part says, “Bovino has been instrumental in informing the public” about the “record-breaking increase in” assault against law enforcement. Agents, it says, “use the minimum amount of force necessary” in dangerous situations and “are highly trained in de-escalation tactics.” The response also says on June 20th, “Border Patrol vehicles were violently targeted during lawful operations.” In Bell, “one vehicle was rammed and had its tires slashed,” it says. And regarding Edgardo’s collision in Maywood: “A civilian struck a federal vehicle, totaling it.” As for Jorge, he declined our interview requests, but Jenny said he was at work delivering coffee supplies the morning immigration agents exploded their way into their home. “They called after and they told him, ‘Did you find out what happened in your house?’ That for me just. That was just not right.” We did not get a response to questions about why federal agents let Jorge go, then, a week later, used such high-risk tactics to arrest him. He immediately turned himself in. Prosecutors didn’t request detention, and a judge sent him home the same day. The Times found no past record of violent offenses. In the federal complaint against Jorge, the prosecutor mentions a previous incident when he allegedly heckled Border Patrol agents. But he’s officially charged with “injuring government property.” And the crux of the case is the accusation that Jorge deliberately collided with the Border Patrol pickup, which had stopped in a manner that should have allowed any car traveling behind him to stop safely. But this claim is directly contradicted by the agent himself. And the allegation of a deliberate collision is not evident in the footage. In fact, brake lights indicate Jorge is braking as soon as the pickup begins to stop. In mid-July, Bovino posted this ominous video of the raid at Jorge’s house, with text warning people will face justice regardless of their immigration status. The next day, Jorge finds out the federal government has dropped the charges. His case is dismissed.

How ‘Turn and Burn’ Immigration Operations Unleash Chaos — and Sweep up U.S. Citizens

- December 21, 2025