Change 2020-25 +47% Long Island City

+60% Greenpoint

+49% Dumbo

+60% Soho

+54% Chelsea

+58% Tribeca

In some of the city’s wealthiest enclaves, even high earners are struggling to keep up with ballooning costs. By Paulina CacheroMax RiveraAnn ChoiRachael Dottle Photographs by Nina Westervelt September 12, 2025

In some of the city’s wealthiest enclaves, even high earners are struggling to keep up with ballooning costs. By Paulina CacheroMax RiveraAnn ChoiRachael Dottle Photographs by Nina Westervelt September 12, 2025

To understand why residents of New York City, the epicenter of American capitalism, are supporting a democratic socialist candidate for mayor, look no further than its warped rental market.

In a city where roughly two out of three residents lease their homes, record-high rents have long bogged down the working class. But these days, more high earners are feeling the squeeze: At least 65,000 households making between $100,000 and $300,000 a year pay a third or more of their gross income to landlords, according to NYC Housing and Vacancy Survey estimates. That’s tens of thousands more than just four years ago.

Some of the acute pain points are in trendy neighborhoods like Manhattan’s Tribeca, Brooklyn’s Greenpoint and Long Island City in Queens, where median rents stagnated or even dipped during the pandemic and then skyrocketed as the city reopened, according to StreetEasy data. In many of these same areas, voters supported democratic socialist Zohran Mamdani in the June mayoral primary, making him the favorite to win the general election in November.

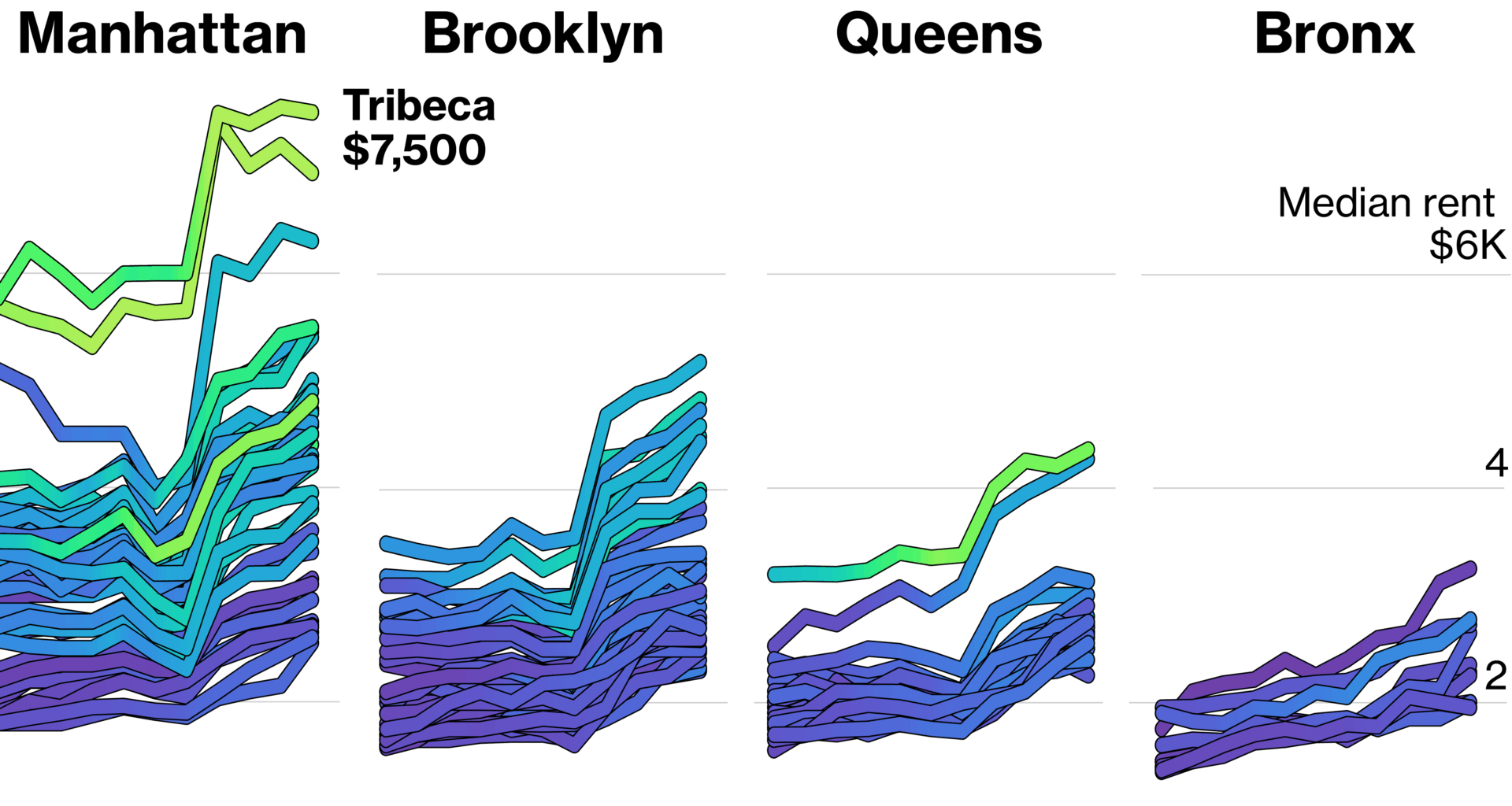

Many Affluent Areas Saw Big Rent Spikes Post-Pandemic

Median asking rent for market-rate apartments by ZIP code

Annual median income of ZIP over time

2050100150200$250K+ 2015202020250246$8KFirst New York COVID-19 state of emergencyWilliamsburg and GreenpointWilliamsburg and GreenpointLong Island CityLong Island CityTribecaTribeca

Sources: StreetEasy, US Census Bureau

Note: Neighborhood names reflect the primary area of the ZIP code. On the chart, Tribeca is ZIP code 10007, Williamsburg and Greenpoint are 11211 and Long Island City is 11101. Staten Island is excluded due to lack of data. Median rent for 2025 through June. Median income of renters comes from the US Census 5-year estimates for 2015–2023, with the estimate for 2023 applied through 2025.

Even though Mamdani’s plans revolve around freezing price hikes for about a million rent-stabilized apartments, his focus on affordability has resonated with high earners in business, finance and tech questioning whether they can live the life they want in the city. In Manhattan, median rent climbed to a record $4,722 in August, according to StreetEasy.

“What has changed is who is feeling the crunch,” said Barika Williams, executive director for the Association of Neighborhood & Housing Development. “It’s spreading all the way up.”

See How Median Rent Has Changed in Your ZIP Code

Median asking rent for market-rate apartments

Manhattan 201520202025$5,768$5,768Median rent:Median rent:$7,500$7,500Bronx 2015202020250246$8K

Sources: StreetEasy, US Census Bureau

Note: Neighborhood names reflect the primary area of the ZIP code. The charts include only ZIP codes where market-rate apartment inventory via StreetEasy was above 100 units. Staten Island is excluded due to lack of data. Median rent for 2025 through June. Median income of renters based on US Census 5-year estimates for 2015–2023; estimate for 2023 applied through 2025. For ZIP code 11249, income data only available 2021–2023 and 2021 estimates used for previous years.

New York has long had some of the world’s most expensive real estate, leading many to rent and, inevitably, complain about those payments being far too high. Still, the post-pandemic period has taken the affordability crisis to new extremes. That’s due to a combination of landlords clawing back Covid-era losses, a surge of luxury development and a frozen housing market that has kept even high-earning families in a rental market where inventory is historically low and bidding wars are commonplace.

From 2020 to 2024, rent in the New York City metro area ballooned by 27%, outpacing other major metros including Los Angeles, Boston and Washington, DC, according to Zillow’s rent index. This year, by most any measure, is shaping up to be even worse.

Greenpoint, at the northernmost tip of Brooklyn, is among the starkest examples of surging shelter costs. The area once known for its industrial roots and Polish immigrant community saw market-rate rents jump around 50% from 2020 to 2024 as more white-collar workers flooded in, some drawn to new developments along the East River. Roughly 72% of its Democratic voters in that neighborhood supported Mamdani in June’s primary, according to New York City Board of Elections data.

In other in-demand neighborhoods like SoHo, Brooklyn Heights and Long Island City, where residents saw rents jump by more than 40%, voters also overwhelmingly supported Mamdani for mayor.

The Eagle + West apartments in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, are one of the many luxury residential buildings in the neighborhood. A view of the Manhattan skyline from the Dumbo waterfront in Brooklyn.

The fact that a 33-year-old democratic socialist could surge from relative obscurity to defeat Andrew Cuomo, the former governor of New York, has captivated political operatives across the US, who are already thinking about next year’s Congressional midterm elections. Some have called it a sign Democratic leaders need to embrace the next generation, while others, including President Donald Trump, have claimed Mamdani’s election will doom the Democratic Party and the nation’s most-populous city.

Mamdani, for his part, has gone on a charm offensive to woo some of the city’s business leaders. While some executives still oppose his campaign, Mamdani’s promises to tackle affordability have garnered support from a broad swath of New Yorkers as soaring costs of living continue to hollow out the city’s middle class.

“The biggest problem facing New York City is affordability. This is the most expensive city in the United States of America,” Mamdani said in an interview with Bloomberg News. “It’s also the wealthiest city in the wealthiest country in the history of the world. And one in four New Yorkers in that same city are living in poverty.”

The question remains how any of Mamdani’s policies, should he prevail in November’s general election, will ease the strain on renters in some of New York’s priciest neighborhoods. Some in the real estate industry have also said that his plan to freeze price hikes would only worsen the housing shortage by discouraging landlords from making repairs.

The big jump in rental prices seen across many affluent New York City neighborhoods follows what economists call “The Great Reshuffle” of Covid-19. Wealthier New Yorkers left the city during the pandemic in larger numbers, prompting many landlords in usually-trendy areas to lower rents and offer concessions. But affluent renters have made a major comeback since then, even as many lower- and middle-income New Yorkers have exited the city. That’s fueled fierce competition over market rentals and squeezed households who by most standards would be considered wealthy.

“I thought by the time I was 26 surely I would be able to afford a one-bedroom in a location I love,” said Cole McMahon-Gioeli, who works in finance. “That feels so far away now.”

Thanks to a Covid-era deal on a two-bedroom on the Lower East Side and a few raises, he currently spends 29% of his post-tax pay on housing costs, still less than the roughly one-third that housing experts define as the outer limit of affordability. But now that his roommate is looking to move out, with the $4,125 going rate of one-bedrooms in the area, McMahon-Gioeli will have to fork over half of his paychecks on rent to live alone.

“I fully expected taking the career path that I took and the sacrifices that come with it that I would have more freedom and choice,” he said. “Instead, I’m still fighting over a limited roster of apartments on StreetEasy that are taken down a day later. I didn’t think it would be like this.”

The Great Reshuffle

There was a brief period during the early months of the pandemic in 2020 when New York’s renters could strike previously unheard of deals. But the rollout of vaccines by early the next year allowed offices to fully reopen and enticed people — especially the wealthy — to return.

Between 2021 and 2023, New York saw a big increase in the number of households earning $100,000 or more, even as it continued to lose lower income households. The city’s share of millionaires also hit a record high, with some recent estimates suggesting one of every 24 residents is worth more than $1 million.

New York Became Wealthier Post Pandemic

New York City households in each income category, 2021–2023

Source: NYC Housing and Vacancy Survey

This upward shift in household incomes resulted from a combination of factors, according to the Housing and Vacancy Survey, including wage increases from raises and job changes as well as the migration of new, higher-income households into the city.

Still, more people are leaving New York than arriving. Those heading out are primarily from the city’s working class who earn $60,000 or less, according to tax data.

Madison Avenue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

The shift has set the stage for landlords who are seeking to recover pandemic-era losses by getting new renters ensnared in bidding wars that are typically reserved for homebuyers.

“It’s much easier to raise rents between tenants,” said Emily Eisner, a chief economist at the Fiscal Policy Institute. “That’s a big part of why all the rents are going up, especially for high-income people.”

The city’s population continues to outpace its ability to build housing, driving many HENRYs — or high earners, not rich yet workers — to rentals as high interest rates and low inventory deter those who might typically try to buy a home. The total number of millionaires renting in the city has nearly doubled from 2019 to 2023, according to an analysis by RentCafe.

More-Expensive Apartments Saw a Bigger Jump in Rent

Asking rent for apartments on StreetEasy, by number of bedrooms

Source: StreetEasy

Note: Includes only ZIP codes where market-rate apartment inventory via StreetEasy was above 100 units. Median rent in 2025 through June.

Ben Miller isn’t squeezed by rent by the rule-of-thumb, but the skyrocketing cost of living has kept the Prospect Heights resident in a holding pattern, passively house hunting while living with his wife and their infant daughter in a newly built rental. Refusing to compromise on location and amenities, Miller, a software engineer, and his wife are among the growing number of high earners hanging onto their space.

For now, Miller plans to stay in his apartment that is close to his wife’s job as a midwife and eligible for one more year of rent regulation under the city’s 421-a program, a partial tax exemption for developers. But once that unit converts to a market-rate rent, the family will have to confront difficult tradeoffs.

“If the rent goes up too much here we might move somewhere else,” Miller said. “We always talked about leaving New York altogether, but I don’t think any of us really wants to do that.”

Mamdani’s signature rent-freeze proposal only applies to the city’s nearly 1 million rent-stabilized units, which are currently capped at raising rents by no more than 4.5%.

Shanée Benjamin in her apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

It nonetheless resonated among renters, from corporate workers like McMahon-Gioeli to artists like Shanée Benjamin.

Benjamin, who makes six-figures as an illustrator, recalls looking at apartments for $500 when she moved to the city as a new college grad in 2013. Now, she’s staring down a $5,500 monthly bill for her two-bedroom apartment in Crown Heights — a 72% rent hike from the year prior — and struggling to find anything cheaper. If something doesn’t change, she worries about the future of New York.

“If you made $150,000, you used to be able to live comfortably,” Benjamin said. “The people coming in are transplants. They’re pushing out native New Yorkers and working class New Yorkers. So who is left here?”

Luxury Development

Politicians have tried to address the city’s challenges with low inventory for years. Mayor Eric Adams, who is running for reelection as an independent candidate, touts his City of Yes plan as having delivered a record amount of new housing.

But a major issue is that much of the new housing supply targets the highest earners.

Experts have repeatedly pointed out that in one of the most expensive cities to build, there’s very little incentive for developers to build affordable housing without substantial government subsidies. Rather, what gets built is almost all upscale, driving up the median rent as new residents sign leases in luxury towers.

Perhaps no other neighborhood exemplifies this trend quite like Long Island City, a former industrial area across the East River from midtown Manhattan. Lisa Goren, who moved to the neighborhood more than three decades ago, has seen it happen firsthand.

Long Island City Gained the Most Apartments

Net new units completed between 2020 and 2024

Sources: US Census Bureau, NYC Department of Buildings

Note: Includes net units added by alteration or new construction based on permits completed in the Department of Buildings Permit Issuance database. Staten Island excluded due to lack of data. The Dumbo neighborhood tabulation area includes parts of Downtown Brooklyn and Boerum Hill.

From 2020 to 2024, there were nearly 7,200 net apartment units added in Long Island City, a majority of which were based in high-rise elevator buildings. New development now makes up nearly a third of Northwest Queens’ rental market, with median rents that are $625 more a month than the typical apartment in the neighborhood, according to data collected by appraiser Miller Samuel Inc.

“The rent crisis in New York City isn’t a housing shortage,” said Goren, who recalls nabbing a two-bedroom apartment for roughly $400 a month in 1989. “It’s an affordability shortage.”

A view of the Long Island City skyline from the 7 train platform in Queens.

(Updates to add rent estimate in fourth paragraph)

Edited by Claire BallentineNadja PopovichCraig Giammona Photo editing by Sophie Butcher