John Irving’s books found me at the perfect time, when I was an unmoored teen. I discovered “A Prayer for Owen Meany” and “The World According to Garp” on the one English shelf at the Israeli bookstore Steimatzky; the novels provided me with just the kind of fantastical escape I needed.

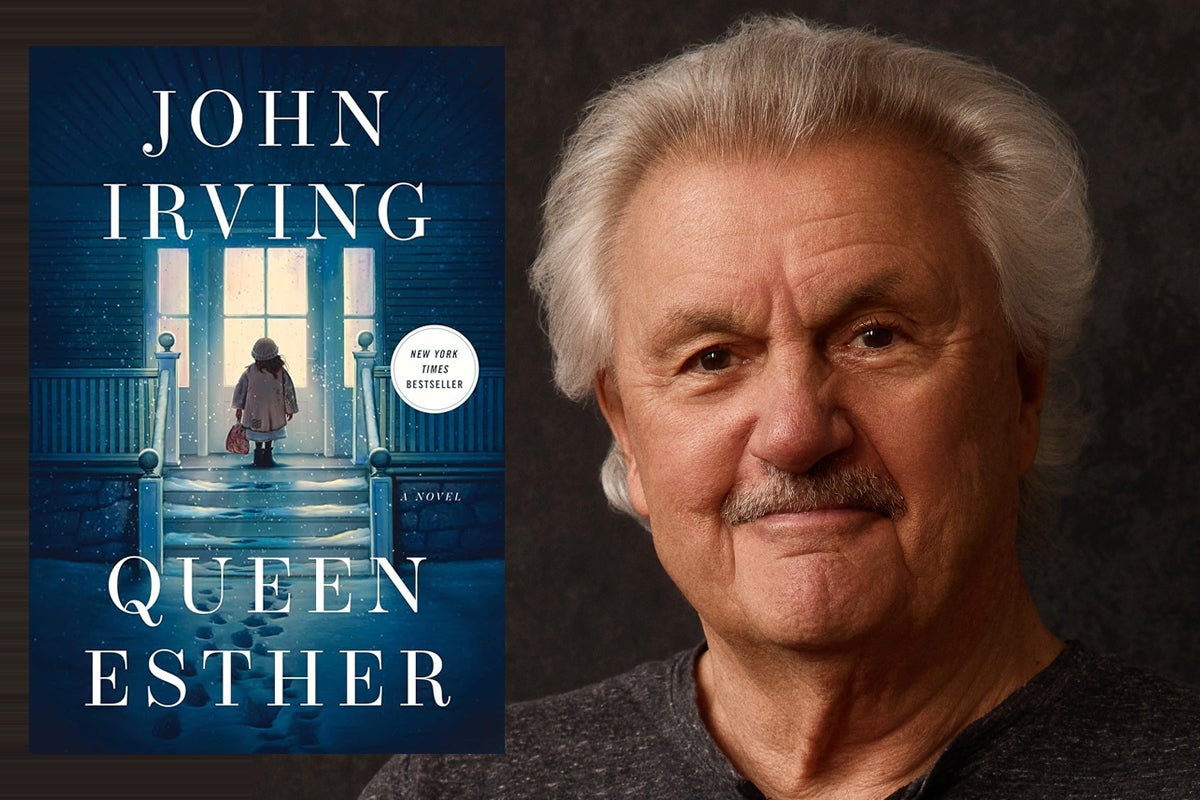

In his newest novel, “Queen Esther,” Irving gives us a Jewish heroine as colorful, high-minded and enjoyable as any of his protagonists. Esther loses her father to illness on the ship from Austria and her mother to an antisemitic hate crime in Portland, Maine. She makes it to an orphanage many John Irving lovers know, the one run by Dr. Wilbur Larch of “The Cider House Rules.” As a teen, Esther is adopted by the literature-loving and fiercely secular Winslows of Penacook, Massachusetts, to help raise the youngest of their four daughters, Honor.

This book has all the elements of Irving’s fiction: a deep concern with history shared in a way that doesn’t feel didactic, a disdain for religion and war, rich representations of queer characters. But here, we also find a repudiation of antisemitism and a sympathetic take on Zionism.

Magic and humor fill the pages, as do Yiddish words for genitalia, a lively debate about circumcision, tattoos quoting “Jane Eyre” and diminutive Jewish wrestlers.

Kveller spoke to Irving about the 1981 visit to Israel that helped inspire this book, his love for Queen Esther of the Purim story, and why he wanted to tell a story of a fierce but empathetic Zionist heroine.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

I was wondering how the character of Esther came to you?

She was the first thing that came to me. As you may know about my process, I am an end-driven writer. It was always my intention that this novel would end in Jerusalem in April of 1981… when Esther would be 76.

If she’s 76, in Israel in 1981, and she’s a Viennese-born Jew, she has to be born in 1905. And I wanted her to be an orphan. A Jewish orphan, before the age of four, whose life is at that time already shaped by antisemitism. It was important to give her a history that, for any person, Jewish or not, you would have to empathize with what this character would want to do. Her Jewish childhood has been stolen from her. She’s had no other Jewish friends, so when she gets out of the orphanage, she has an agenda. To become, in her estimation, the best Jew she can be.

It was always my intention to send her in the wrong direction at the wrong time. She’s going to Vienna in the 1930s, when many Viennese-born Jews have already left or were in the process of leaving, and she will, as one of them, be among those European Jews who determine that she belongs in what was the land of Judah, the land of the Israelites.

Why did you feel like it was right to go back to St. Cloud and Dr. Larch of “Cider House Rules”?

I often struggle with the beginnings of my novels because I know so much more about where they end. I often start the first chapter and then think:, This might be better as a second or a third chapter. So I start another first chapter. But for the first time, I knew almost as much about the beginning of this novel as I knew about the end because I needed a Jewish orphan who was orphaned when she is old enough to know she is Jewish, to know the Esther she was named for. And well, I already knew the orphanage physician. He’ll be much younger than readers or moviegoers who know “Cider House Rules” will remember, but he had to be younger because I wanted an entirely different cast.

What’s your relationship to the story of the biblical Esther?

I always loved that story. In my prep school years, I took a wonderful course in the Old Testament as history — what was likely true, or what was based on history, and then what was made up. And the Book of Esther was just a marvel to me. I love that character. The outrageousness of the very idea of a Jewish Queen of Persia. Her Jewishness… hidden until she comes out — and then watch out! A modern equivalent to her in my imagination was [to] create an empathetic Zionist. If anyone knows that being Jewish is not safe, Esther knows.

There’s such a wonderful cast of Jewish characters in this book. There’s Moshe, a Jewish wrestler and Jimmy’s biological father, and Jonah, his Jewish friend in Vienna. What was the inspiration for them?

I have a history in my novels of identifying with characters that I am not. I have long been an ally of women’s rights and abortion rights, and I’m not a woman. But I grew up with a mother who was a nurse’s aide, and whose job was counseling young, unmarried women who were pregnant, both before and after Roe v. Wade. She brought her work home with her, so to speak. I had a younger brother and sister, boy-girl twins, who were gay and lesbian. I knew enough to be afraid of how they would be treated. And so I’ve long been an ally of LGBTQ+ characters in my novels. Growing up in a small New Hampshire town, I didn’t know any Black kids. I knew very few Jewish kids, but starting at the age of 15, I was in an international boarding school where students came from everywhere in the United States, everywhere in the world. And my wrestling teammates, among them were the first Black kids and the first Jewish kids that I became really close to.

The Jewish kids told me stories of what it had been like to be Jewish, , and the Black kids told me the same stories. And I felt myself an ally to them.

When I was a student in Vienna in the ’60s, I had a Jewish roommate. He opened my eyes to the antisemitism in Vienna, and he was very much on my mind [while writing this book]. He was still alive when I first went to Israel in the spring of 1981. And when I went back to Israel in the summer of 2024 to check my facts with Israeli readers, my Israeli friends who had read the first draft of this novel — that Jewish roommate had died, and it was very sad for me to realize that he’d read all of my novels in manuscript. But he never got to read this one, and I had always imagined when I was writing it: Oh, I think Eric is gonna love this one the most of all. So, he was very much a presence.

It’s obvious in this novel that I am pro-Jewish and pro-Israel. It is also a connection that I share with Jimmy. The first European publishers to translate me and to publish me were European Jews with longstanding ties to Israel.

How did that first visit to Israel in 1981 shape you?

I always travel with a notebook. I was taking notes because it was new to me. And so I wrote down what people were telling me, the dialogue that I heard, everything that was said to me. I was learning. I was a student.

In April 1981, when I left Jerusalem, I had a distinct foreboding of an eternal conflict — of an everlasting conflict. I felt it very strongly that the seeds were already sown for what seemed to me to be a permanent friction, a permanent unrest. And I wanted this novel to foreshadow those feelings. When I went back to refresh my visual memory of those details from 43 years ago, the [Israel-Hamas] war in Gaza was ongoing. Jerusalem was a war zone. The Old City was deserted. Tourists don’t go to war zones. I felt — not only is the conflict eternal, but it’s worse than I ever imagined.

In this book, you write about abortion rights, antisemitism, LGBTQ+ rights — all things that feel so dire right now. Do you have any thoughts about that?

I’m not a current events writer. There’s a reason for that. I trust history. I believe that the past is a mirror that reflects what’s going to happen. Think of how many years after the war in Vietnam “A Prayer for Owen Meany” was written. I knew that in those years, at the time of the Vietnam War, everything associated with it was a hot subject. Everything associated with it made me angry. And I knew that if I waited for enough time to pass that I would know the difference between those things that still made me angry and those things that, over time, I realized were only peripheral.

There’s a moment in this novel, which meant a great deal to me in those Vienna chapters. When the little boy, Siegfried, is frightened because one of Jimmy’s roommates makes a mistake in German. Sigfried has never seen a telescope before, and he wonders what it is. And Claude, Jimmy’s roommate, thinks he says to Siegfried: “It sees into the distance.” That’s what he meant to say… But Claude uses the wrong word, and instead uses the word for “future.” Siegfried is frightened and doesn’t want to look at it. And Jimmy tries to apologize to Siegfried’s mother, and says, I’m so sorry this happened. It should not have happened that we frightened Siegfried about this telescope that sees into the future. Siegfried’s mother says, “There is a telescope that sees into the future, Jimmy, it’s called the passage of time.”

Well, I put in her words what I believe. The passage of time is a truthful teacher.

Can we ask?

It’s important to us to keep the warm, joyfully Jewish community on Kveller accessible for all. Reader donations help us do just that. Can you spare a few to keep Kveller free? (We’ll love you forever.)

Lior Zaltzman is the deputy managing editor of Kveller.