Hell’s Kitchen residents will get a chance this evening (Wednesday) to weigh in on what could become one of the largest physical transformations of Manhattan’s waterfront in decades.

A cruise ship comes in to dock at the current configuration of the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photo: Phil O’Brien

A cruise ship comes in to dock at the current configuration of the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Manhattan Community Board 4 (MCB4) will hold a public hearing on the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) Master Plan for the Manhattan Cruise Terminal — a proposal that would push the piers up to 650 feet farther into the Hudson River, demolish and rebuild much of the existing terminal and permanently redraw the edge of the West Side shoreline.

Since December, when EDC first outlined the plan to the board’s Waterfront, Parks & Environment Committee, the agency has delivered a near 300-page Navigation Safety Risk Assessment — a dense technical document designed to clear a crucial federal hurdle: approval to deauthorize part of the Hudson River’s protected navigation channel so the terminal can expand into it.

Former MCB4 chair Jeffrey LeFrancois — who led the board’s pushback against EDC and Vornado over the Pier 94 redevelopment — told W42ST that he was “shocked” by the scale and sequencing of the cruise terminal proposal. “They are giving away the waterfront all over again,” he said, arguing that any project requiring a federal exemption, the disruption of acres of marine estuary and the alienation of parkland “should raise serious concerns,” after decades of work to make the Hudson cleaner, safer and more accessible.

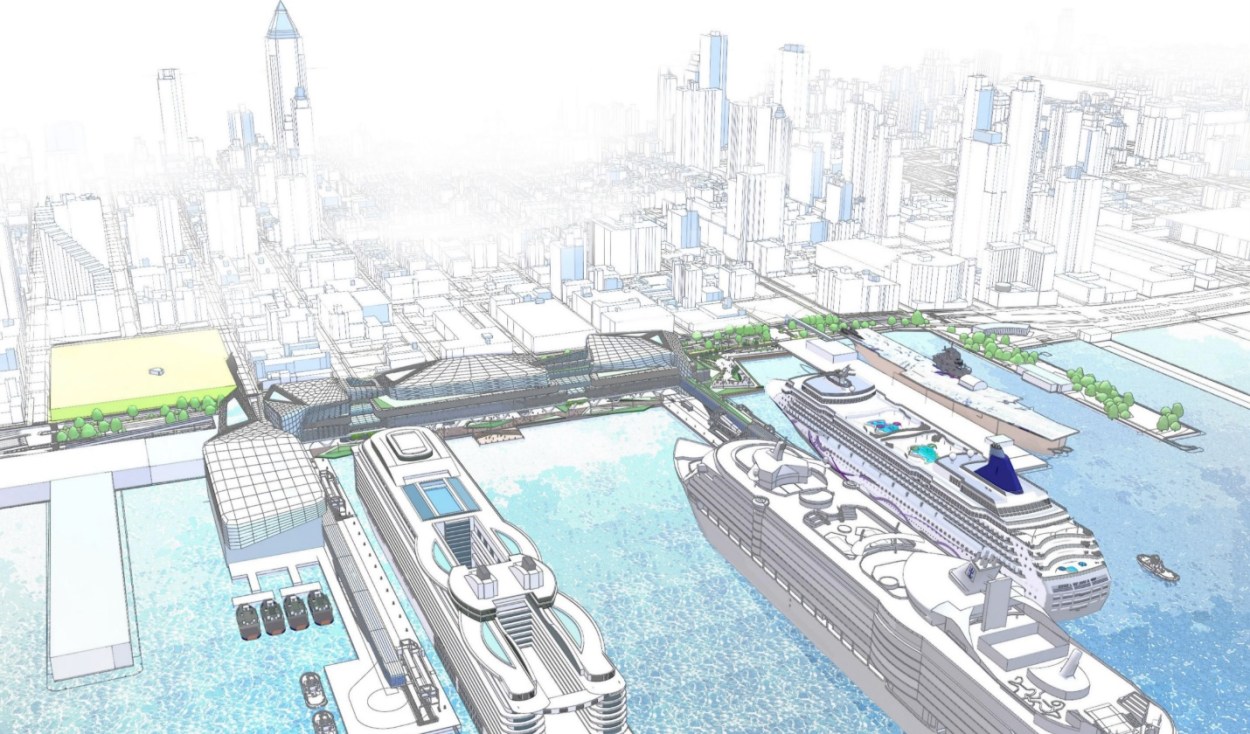

The Master Plan for the Manhattan Cruise Terminal would transform the far West Side and the Hudson River. Rendering: EDC

The Master Plan for the Manhattan Cruise Terminal would transform the far West Side and the Hudson River. Rendering: EDC

The Master Plan envisions replacing the current, deteriorating terminal with a massive, airport-like complex: two newly constructed mega-piers, a rebuilt terminal building, elevated arrival and departure decks, a consolidated ground transportation area to pull buses and cars off 12th Avenue, shore power for ships, new public plazas and a pedestrian bridge over the West Side Highway from DeWitt Clinton Park at W52nd Street.

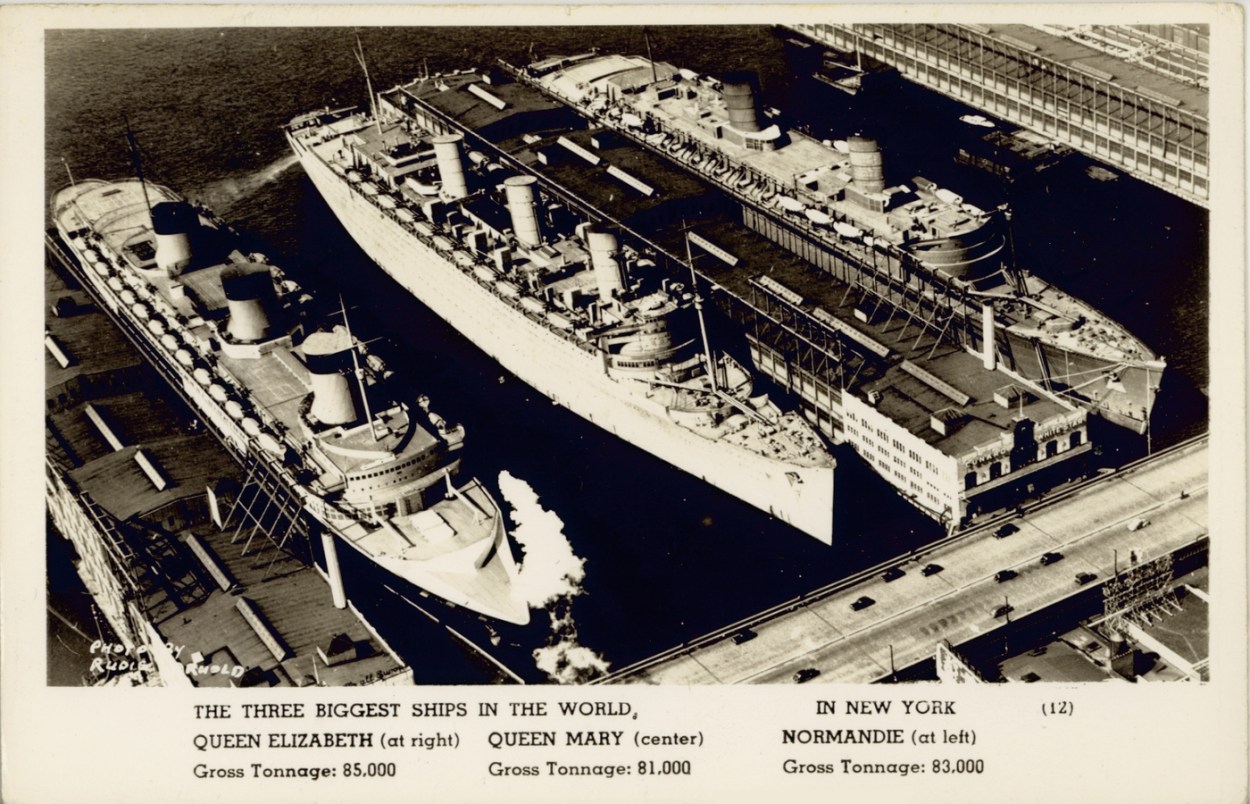

The original New York Passenger Ship Terminal once stretched across six piers between W44th and 54th Streets, created in the early 20th century to replace the aging Chelsea Piers and handle ever-larger ocean liners. In the 1930s, the city was forced to radically re-engineer the shoreline after the US Army Corps of Engineers refused to let the piers extend farther into the Hudson: instead, Manhattan was literally cut back, with bedrock removed — a change still reflected today in the bend of the West Side Highway. By the 1960s the complex had fallen into disrepair, and the current terminal at Piers 88-92 was built in the early 1970s.

A central driver of this redesign is the sheer scale of modern cruise ships. Newer vessels are far larger than those the terminal was originally built to handle, with some carrying close to 10,000 passengers and crew. EDC argues that the existing piers and terminal layout cannot safely or efficiently process ships of that size — a mismatch that is now colliding with aging infrastructure and is one of the core reasons the agency says a full rebuild, rather than piecemeal upgrades, is necessary.

In 1940, The three largest ships in the world, Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary and Normandie docked at the piers. Postcard: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

In 1940, The three largest ships in the world, Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary and Normandie docked at the piers. Postcard: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

LeFrancois warned that the plan’s scale has not been fully absorbed by the neighborhood. “We’re being asked to accept piers that could bring up to 20,000 passengers at a time — roughly the capacity of Madison Square Garden,” he said. “That’s a huge number for a terminal where everyone exits in the same direction and every vehicle has to cross the busiest bikeway in North America.”

To make that possible, the shoreline itself would move. Pier 90 would be demolished. Pier 92 would be rebuilt. And the new cruise slips would extend hundreds of feet farther into the Hudson than they do today.

EDC has not put a price tag or timeline on the project, but at the December meeting, David Lowin, the agency’s Senior Vice President for Development and Asset Management, described it plainly: “It’s an expensive project — it’s in the billions of dollars,” he said, outlining a complex public-private funding model in which government would pay for marine infrastructure while the private sector helps finance the terminal itself.

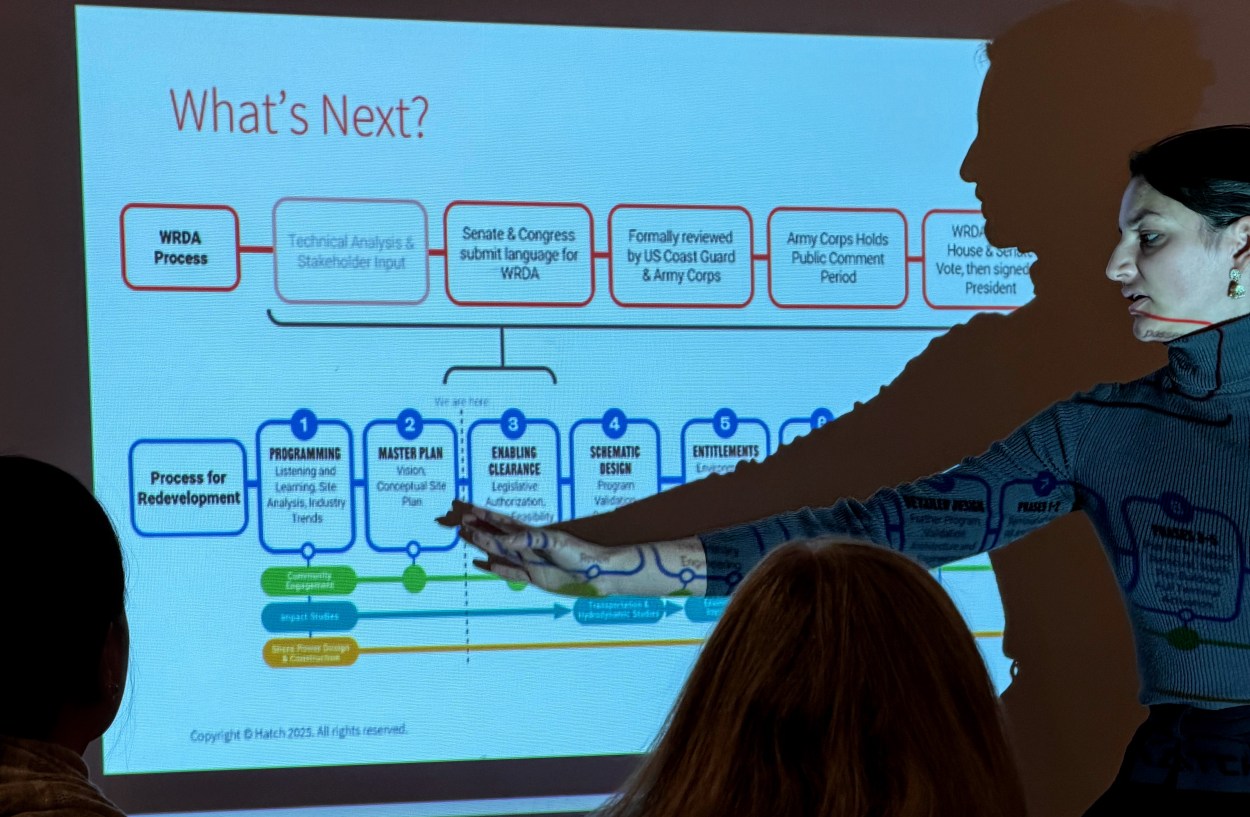

EDC project leader Tara Das presents the Manhattan Cruise Terminal Master Plan timeline to MCB4’s committee. Photo: Phil O’Brien

EDC project leader Tara Das presents the Manhattan Cruise Terminal Master Plan timeline to MCB4’s committee. Photo: Phil O’Brien

EDC says the reason the project has grown from a shore power retrofit into a full master plan is that earlier efforts studied individual problems in isolation. “Shore power is something that EDC has looked at from different angles over the years,” said Tara Das, the agency’s project lead. “We were trying to study it without knowing the conditions of the piers.” The master plan, she said, is meant to create “a framework to guide our future planning… recognizing that this is a huge piece of infrastructure in a very old area of the city.”

In a draft response letter scheduled for a vote at this month’s Full Board meeting, MCB4 strikes a cautious and at times uneasy tone. While welcoming elements of the plan such as new public space, improved pedestrian access and efforts to pull cruise traffic off 12th Avenue, the board says too much remains undefined and unresolved. The letter questions whether alternatives exist that would not require extending the terminal into the Hudson River and warns that many of the project’s promised benefits appear contingent on “reclaiming space along the shoreline and into (or over) the Hudson River.” It also flags the pace of the federal approval process, saying the accelerated timeline is compressing meaningful community review and making it difficult for the board to offer fully informed comment.

LeFrancois said the draft letter itself shows how rushed and upside-down the process has become. “Given EDC’s rushed work, it’s remarkable how the letter provides an alarming amount of support for such a massive, transformative project given the litany of outstanding questions,” he said. He also warned that the plan fails to account for other major projects already underway along the river, including the state’s redesign of Route 9A and Hudson River Park’s own redesign plans further south.

Former MCB4 Chair Jeffrey LeFrancois says: “They are giving away the waterfront all over again.” Photo: Phil O’Brien

Former MCB4 Chair Jeffrey LeFrancois says: “They are giving away the waterfront all over again.” Photo: Phil O’Brien

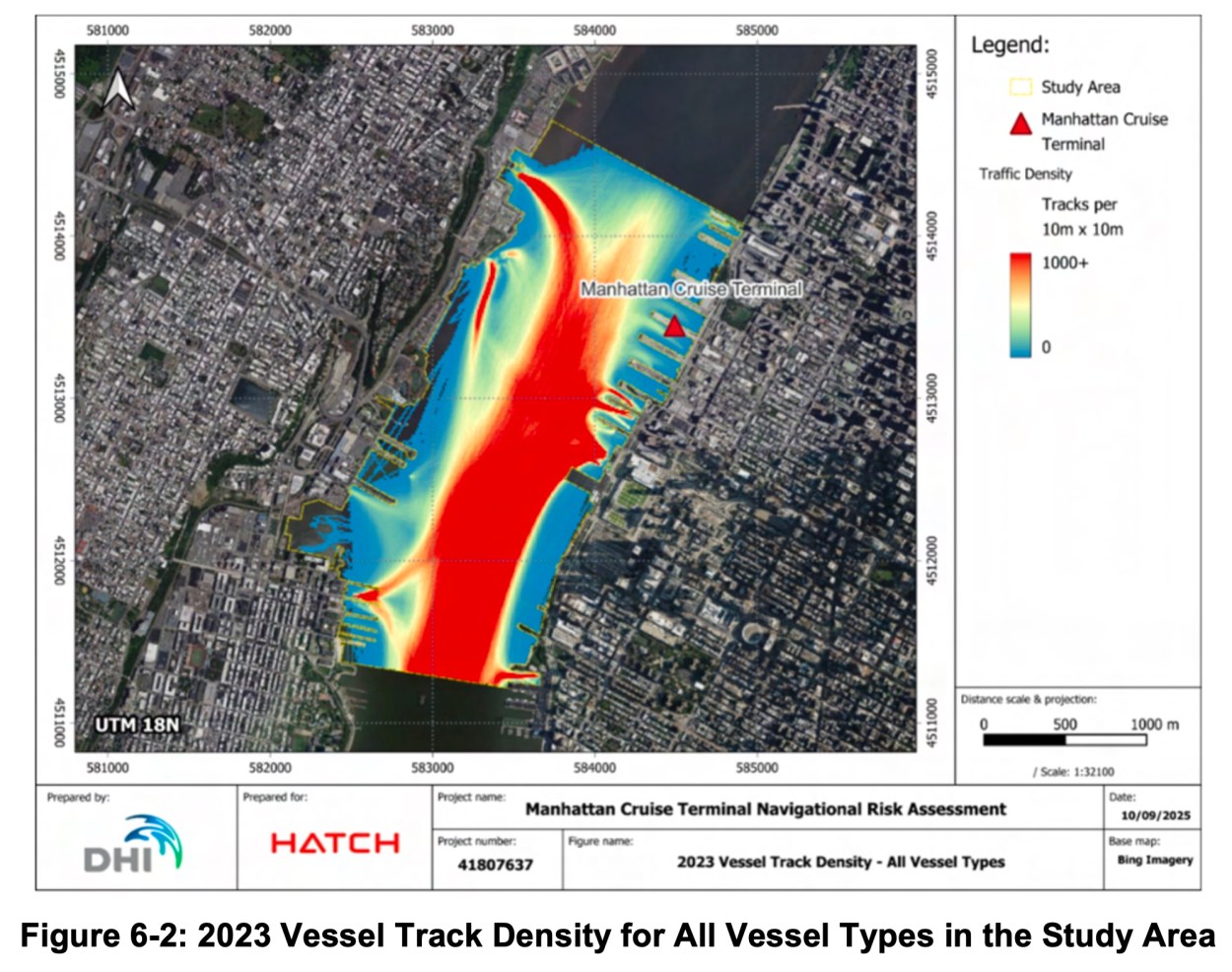

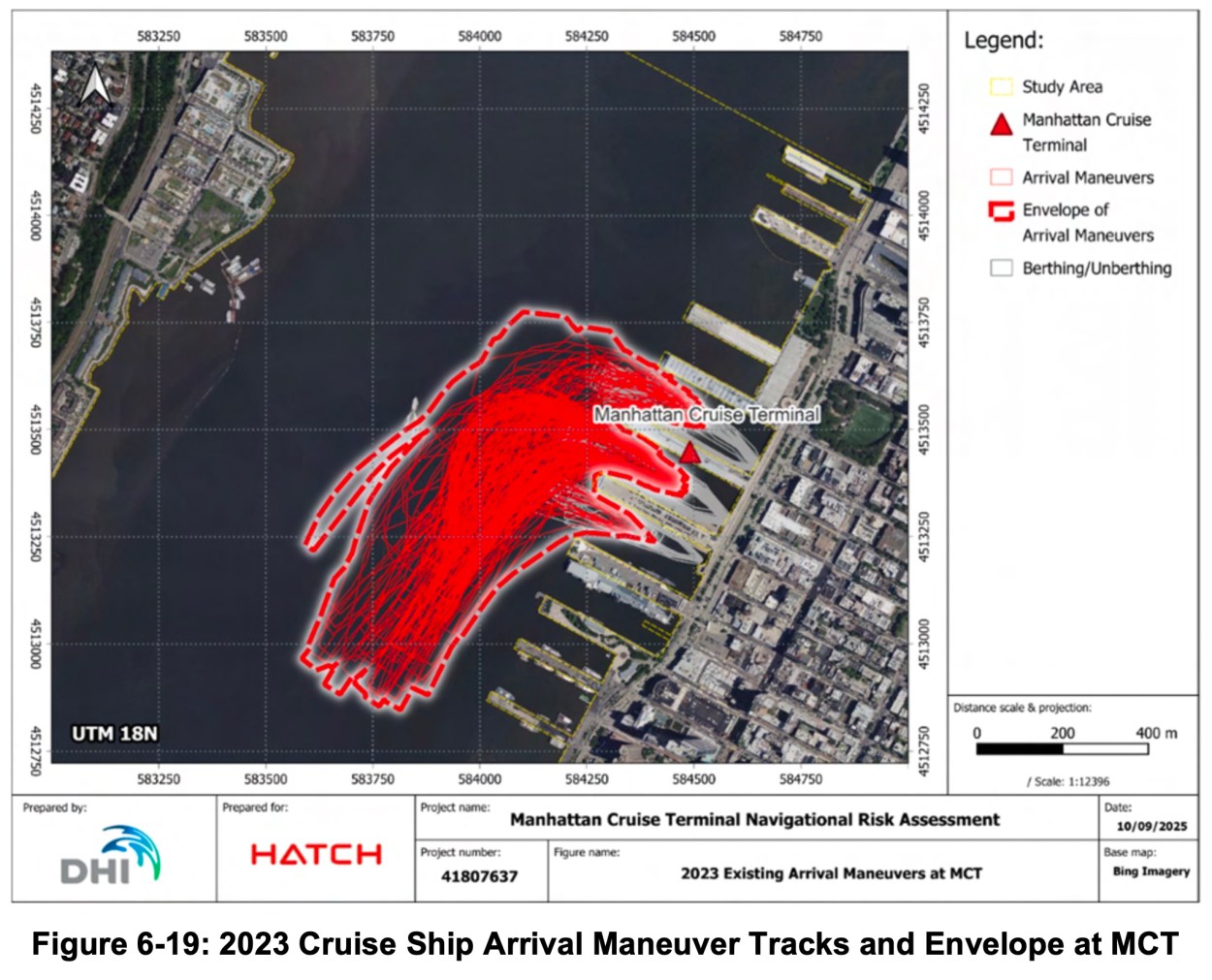

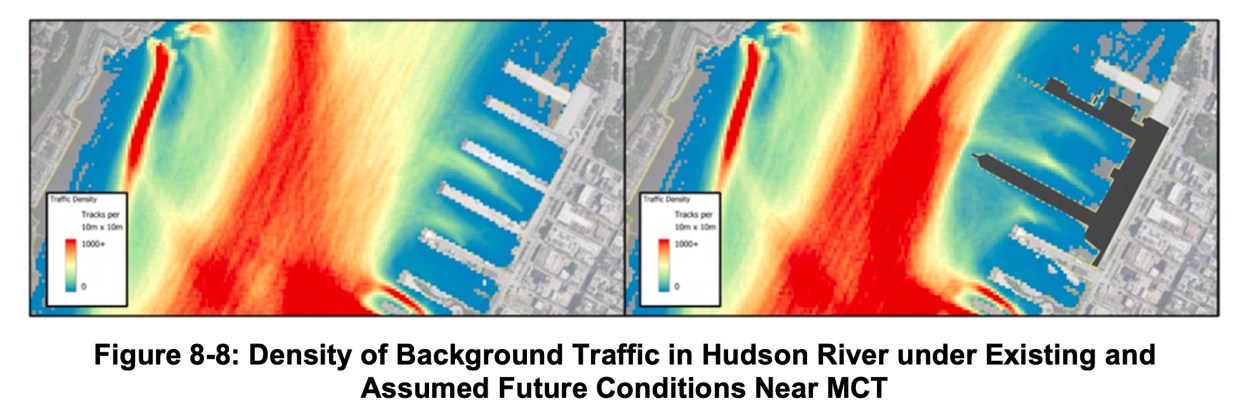

The new navigation report is meant to answer one narrow but pivotal question: can the river safely absorb this expansion?

At its core, the bulky document says yes. Using historical vessel tracking data, it concludes that 93.61 percent of ships using the Hudson would be “unimpacted” by the new pier footprint. It acknowledges a slight increase in the risk of collisions or vessels striking structures, but says grounding risk would remain unchanged — and quantifies the added impact as roughly one additional collision or allision every 17 years, which it characterizes as acceptable for a working harbor.

To test whether today’s largest cruise ships could still maneuver safely, the consultants ran desktop simulations using an “Icon Class” vessel as a stand-in for future ships. Those simulations found that ships could berth and unberth under “typical extreme” Hudson River conditions. About half the runs were rated fully successful; the rest were labeled “marginal,” meaning they required sustained high thruster use but did not fail.

Images from the 294-page Navigation Safety Risk Assessment for the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photos: Hatch/EDC

The report also notes that pilots, tug operators, ferry companies, city agencies and recreational boaters were consulted, and argues that any increased risk could be managed through scheduling coordination, monitoring systems, new signage and revised operating procedures. Throughout, the expansion is framed as a practical necessity: the piers are aging, ships are getting larger, and shore power is presented as a central justification for rebuilding the terminal in a new configuration.

But even within its own pages, the report shows why that conclusion is likely to be contested — especially in a neighborhood that has spent decades reclaiming its waterfront for public use.

The study defines “acceptable risk” strictly in technical terms. It does not ask whether residents, park users or small-boat operators should accept any additional risk at all in exchange for cruise expansion. “One additional accident every 17 years” may sound negligible in statistical language, but the report does not grapple with where such an accident might happen, who would be affected, or how it would play out in one of the most congested stretches of the river.

Some of the river’s most vulnerable users are also the hardest for the study to model. Kayaks, rowing shells and paddleboards do not carry AIS tracking devices and barely appear in the data sets driving the analysis. While the report acknowledges this gap, it proceeds anyway, relying largely on behavioral mitigations.

Hell’s Kitchen resident and kayaker David Janowski speaking at the MCB4 WPE committee meeting in December. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Hell’s Kitchen resident and kayaker David Janowski speaking at the MCB4 WPE committee meeting in December. Photo: Phil O’Brien

That concern was raised directly by Davis Janowski, a Hell’s Kitchen resident, journalist and kayak guide, who told the committee that the waterways off Midtown are far busier than official studies often suggest. “There are hundreds if not thousands of trips every year that go past that area,” he said. He warned that many small boats rely on weaker radios than commercial vessels, and that pushing recreational users farther into the channel could increase risk rather than reduce it.

The report’s headline statistic — that 93.61 percent of vessels would be “unimpacted” — also masks where the impact actually falls. The ships that will have to adapt are those already operating in the tightest, most crowded waters near the terminal. The report concedes that passing distances shrink and maneuvering space tightens, but treats that as acceptable because the effect is localized. For Hell’s Kitchen, that localization is the issue.

The simulations rely on a single representative ship type and a relatively small number of runs. Nearly half were rated “marginal,” a category the report accepts, but one that raises questions about margins for error as ships grow larger and weather becomes less predictable.

And perhaps most consequentially, the document is designed to clear a federal hurdle before the full project is defined. EDC is asking Congress to give up a protected navigation corridor now, based on a conceptual plan, before final designs, budgets or timelines exist.

Das has been explicit that this is only the beginning of that process. “We are at step zero,” she told the committee, describing the next phase as a bid to change the federally authorized channel boundary through a multi-year legislative process. “Because we don’t yet know whether we’re going to be able to have this geography or not, we can’t say we’re going to deliver a cruise terminal in X years,” she said.

Once river space is surrendered, critics note, it is rarely reclaimed. Tom Fox, who helped shape Hudson River Park and now serves on its advisory council, warned that the plan would effectively give up roughly nine acres of protected estuarine sanctuary. “It took us 20 years to map this,” he said. “You’re covering it over. There should be huge contributions to estuary restoration.”

Paddlers from Manhattan Kayak Club out on the Hudson River near the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Paddlers from Manhattan Kayak Club out on the Hudson River near the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Whether the Master Plan ultimately takes 10 years or 30, and whether it costs two billion dollars or 10, one thing is certain: if approved, it will permanently change the shape of the Hudson River at Hell’s Kitchen. For now, the shoreline is still being debated.

MCB4 January Full Board Meeting — Hybrid meeting

Wed, Jan 7 | 6:30-9pm

Pier 57 Classrooms, 25 11th Ave (W15th St)

More details and how to participate at https://cbmanhattan.cityofnewyork.us/cb4/meeting/full-board-60/