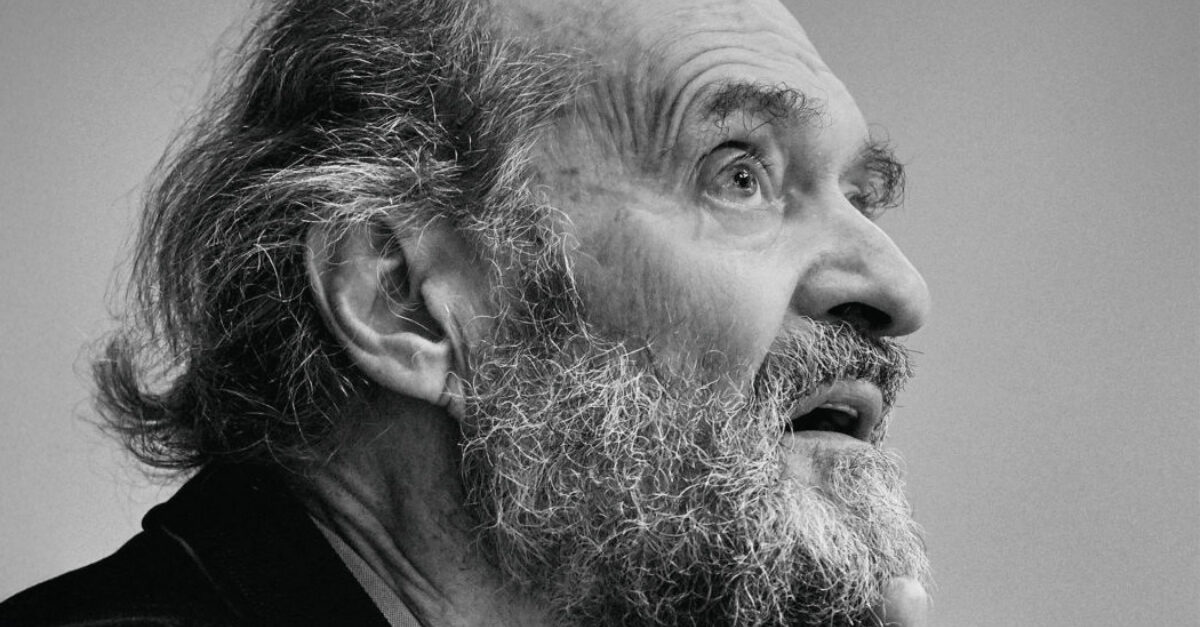

For some, his name may be unfamiliar, though his oddly calming music has found its way into countless film and television soundtracks. Name recognition aside, Arvo Pärt is a very big deal. For the past 10 years, he has been among the world’s most-performed living composers. But his reach extends far beyond the world of classical music.

You are as likely to hear his works played in concert halls and churches as before a Sigur Rós arena show. You’ll hear about him from Yannick Nézet-Séguin or Gustavo Dudamel as well as from Jonny Greenwood, Björk, or Michael Stipe. He is Laurie Anderson’s favorite composer—she made the pilgrimage to the Arvo Pärt Centre in rural Estonia last year, as did Sting and 20,000 other visitors. He is loved by fans of the jazz-focused ECM record label that discovered him in the 1980s, and surprisingly to some, he has a devoted following among heavy metal aficionados.

Pärt turns 90 this year, and the 2025–2026 concert season is abuzz with Pärt-themed concerts and festivals worldwide. He was named this season’s holder of the Richard and Barbara Debs Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Hall, a celebration that kicks off with the Estonian Festival Orchestra and Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir conducted by Paavo Järvi on October 23 for a career-spanning all-Pärt concert. The next evening, the same choir performs alongside the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra for another jewel of an all-Pärt program.

But who is this composer, whom nobody and everybody seems to know? Born in 1935 in Estonia, taking up studies in music composition, his star rose quickly among his fellow Eastern-European composers. Several of his 12-tone compositions in the 1960s got the attention of the music world, but also of the Soviet authorities who were making it increasingly hard to be creatively—and spiritually— free. His 1968 composition Credo, a tempestuous piece jumping jaggedly between serenity and cacophony, marked a turning point. For the eight years that followed, he composed almost nothing apart from film scores. But he emerged in 1976 with a few whisper-quiet works—such as Für Alina and Spiegel im Spiegel—that remain among his most often-heard pieces. With these he inaugurated his signature method, called tintinnabuli (meaning, “little bells”).

The ensuing compositions included the classics that captivate a wide listenership. Uncannily, the 100-odd post-1976 works—whose style, length, and instrumentation vary widely—all come to be characterized typically by a small constellation of words: Stillness. Silence. Transcendence. Ask his listeners and they will say the music is still and stirring, silent and quieting, transcendent and transporting. What defies logic is that the music itself can sometimes measurably be loud, at times even booming. It is sometimes busy, at times even frantic. Yet there is something about its effect that inexplicably bears the traces of quiet, of hush, of something that clears away your inner clutter.

Perhaps one clue to these paradoxes lies with another quality of this music: Reverence. Pärt’s post-1976 oeuvre consists overwhelmingly in sacred music. Most of his compositions are set to texts from the Psalms, from the Gospels, or from prayers traditional to the Christian East and Christian West. The sacred resonance of these words conveys itself palpably (though never preachingly) to listeners regardless of their faith, agnosticism, or atheism. It is as if what matters is the composer’s own attitude. Himself a member of the Orthodox Christian Church, his relationship with the sacred texts that he sets to music is one of loving devotion. His music is something akin to a prayer that he is offering; it reflects his own inner life. Whether or not a listener is a believer of any formal faith, the composer’s disposition communicates itself through the music. The result is a focused, reverential space.

But Pärt’s music is more than just serene. It has a reputation—again from diverse quarters and faith-locations—for serving as an accompaniment to those who are suffering. Such experiences were brought to wider attention through Alex Ross’s remarkable essay nearly 25 years ago in The New Yorker, “Consolations.” Ross describes the reports of people in hospices, how they developed an attachment to this “angel music.” He writes, “Several people have told me essentially this same story about the still, sad music of Pärt—how it became, for them or for others, a vehicle of solace. One or two such anecdotes seem sentimental; a series of them begins to suggest a slightly uncanny phenomenon.” His music is more than just calm; it is, on the whole, mournful—but in a way that is empathetic rather than saddening. People listen to it and feel heard and accompanied in their suffering, which leaves them feeling there may be something beyond suffering, something of hope.

One further feature of Pärt’s music is worth mentioning again, and that is how often it is chosen to accompany other works of art. Pärt’s compositions feature on the soundtracks of a wide diversity of movies (IMDb lists more than 100), from art-house films to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. A significant proportion of the dozens of books and doctoral theses written about Pärt study this phenomenon. Visual artists like Gerhard Richter and Bill Viola have collaborated with Pärt, as has Robert Wilson, who set his Adam’s Passion to several major Pärt compositions.

His pieces have been at the basis of modern choreography: Christopher Wheeldon set two Pärt works for his ballet After the Rain, but there are dozens upon dozens of other dance pieces undergirded by Pärt pieces, likely stemming from the evocative nature of these compositions: As still as they may be, they are also stirring. They are both serene and stunning. Michael Stipe famously characterized Pärt’s music as “a house on fire and an infinite calm.” It is a strange juxtaposition, an oxymoron, yet experience testifies to how it is so.

Pärt’s music isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. Especially as he came to be adored by critics and audiences during the 1980s and ’90s, there was a small backlash among commentators who found his music too simple, even gimmicky. There is room for all opinions, of course, but the avalanche of concerts, festivals, and write-ups we are beginning to see during Pärt’s 90th birthday season leaves a pretty incontestable impression as to the seismic impact of this still, yet stirring body of work.

Visit CarnegieHall.org.