The Manhattan Cruise Terminal has lost one of its working piers. Pier 90 has been taken out of service just as the city is pushing a sweeping plan to rebuild and expand the facility into the Hudson River.

Pier 90, photographed in April 2022, is no longer in operation at the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Pier 90, photographed in April 2022, is no longer in operation at the Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Photo: Phil O’Brien

At last week’s Manhattan Community Board 4 full board meeting, the city’s Economic Development Corporation announced that Pier 90 is no longer able to accept cruise ships, leaving Pier 88 as the terminal’s only functioning berth and throwing new urgency — and new skepticism — onto the agency’s sweeping Master Plan to rebuild the West Side terminal and push it hundreds of feet farther into the Hudson River.

EDC says the closure is the inevitable result of decades-old infrastructure finally giving way. Speaking to the board, Allison Dees, a senior project executive at the agency, said the Midtown piers are “really approaching the end of their useful life.” Pier 92, she noted, has been inoperable since about 2019. Pier 90, she said, has seen a “dramatically reduced number of cruise ship calls” in recent years because its interior layout no longer works for modern customs, security and baggage operations. “And actually, starting this year, [on] that pier we are no longer going to be able to accept any additional cruise ship berthing,” Dees told the board. “The infrastructure of both is really deteriorating. This is not a surprise. It’s 100 years old.”

Allison Dees from the EDC tells the Community Board that Pier 90 will no longer be operational. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Allison Dees from the EDC tells the Community Board that Pier 90 will no longer be operational. Photo: Phil O’Brien

She described Pier 88 as the terminal’s current “workhorse,” and said the condition of the piers is a central reason EDC shifted from studying individual fixes to pursuing a full Master Plan.

For the Community Board, however, the sudden loss of Pier 90 landed as a shock.

“We were as surprised as anyone when we were told Pier 90 has now been deemed inoperable,” said Leslie Boghosian Murphy, Manhattan Community Board 4 chair. “This was not part of any equation in all of our conversations with EDC leading up to this point. Yes, it acutely illustrates the need for a serious update at the Manhattan Cruise Terminal — but it also begs the question: how was it allowed to get this bad in the first place?”

The EDC present the Master Plan at the MCB4 meeting last week. Photo: Phil O’Brien

The EDC present the Master Plan at the MCB4 meeting last week. Photo: Phil O’Brien

For now, all cruise traffic at the terminal is being funneled through Pier 88. EDC has said there is a possibility that the first 300 feet of Pier 90 — which sits on solid ground — could still be used for limited docking during July’s Sail4th and America 250 events, but engineers are still evaluating whether that is feasible.

Figures confirmed by EDC show the terminal handled 185 ship calls in 2023 and is scheduled for 127 in 2026 — a reduction of 58 visits, or about 31 percent. EDC has acknowledged that passenger volumes will decline in the near term due to reduced effective terminal capacity.

The loss of Pier 90 adds real-world weight to EDC’s argument that the terminal is no longer viable in its current form. It also sharpens a deeper dispute: whether this state of disrepair reflects unavoidable aging — or years of neglect.

“EDC assumed control of four working commercial piers at the Manhattan Cruise Terminal when they were removed from the Hudson River Park plan in the late 1990s,” said Tom Fox, who helped shape Hudson River Park and now serves on its advisory council. “They’ve allowed the construction of a movie studio on Pier 94, and their inadequate maintenance has rendered Piers 92 and 90 inoperable, leaving Pier 88 to host all cruise ship visits in the foreseeable future.”

Fox added that the failure undermines confidence in what comes next. “EDC failed to manage the existing Manhattan Cruise Terminal. Why should they be trusted to plan and implement a grandiose scheme to cover nine acres of the park’s estuarine sanctuary to accommodate ships that could overwhelm our West Side in Hell’s Kitchen?”

The warning lands harder when set against how Hudson River Park itself treats aging marine infrastructure. In its most recent financial filings, the Hudson River Park Trust notes that since its creation in 1998, its single largest capital expense has been repairing and rebuilding decaying piers inherited in poor condition. The Trust has spent well over $100 million stabilizing and reconstructing Pier 40 alone, and another approximately $50 million on marine capital maintenance elsewhere in the park — including repairs to piles, decks, bulkheads and smaller marine structures. In one case, the Trust rebuilt 690 linear feet of bulkhead near Morton Street at a cost of about $17 million. The message is blunt: waterfront infrastructure survives on constant, expensive, hands-on stewardship.

Pier 92 has been inoperable since about 2019. Photo: Phil O’Brien

Pier 92 has been inoperable since about 2019. Photo: Phil O’Brien

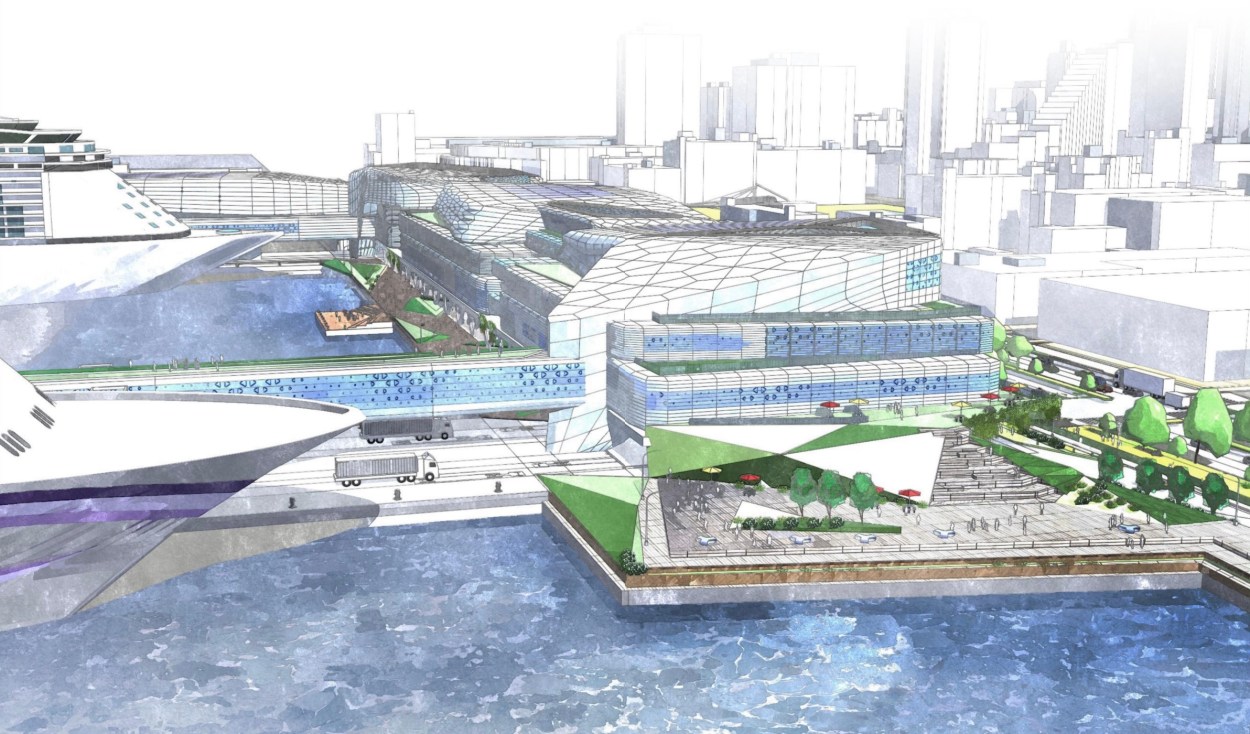

That question now hangs over a Master Plan that would radically remake the waterfront. The proposal calls for demolishing and rebuilding much of the existing terminal, replacing it with two massive new piers, a rebuilt terminal building, elevated arrival and departure decks, a consolidated ground transportation area to pull buses and cars off 12th Avenue, shore power for ships, new public plazas and a pedestrian bridge from DeWitt Clinton Park over the West Side Highway. To make it all work, the new piers would extend up to 650 feet farther into the Hudson River than the current shoreline.

A central driver of the redesign is the sheer size of modern cruise ships, some of which now carry close to 10,000 passengers and crew — far more than the terminal was ever built to handle. EDC argues that the combination of aging infrastructure and ever-larger ships makes piecemeal fixes impractical.

The Manhattan Cruise Terminal has been rebuilt before — but only at rare, consequential moments in the city’s history. The original New York Passenger Ship Terminal, built in the early 20th century, once spanned six piers between W44th and W54th Streets to replace the aging Chelsea Piers and accommodate ever-larger ocean liners. In the 1930s, the city was forced to radically re-engineer the shoreline after the US Army Corps of Engineers refused to allow the piers to extend farther into the river; instead, Manhattan was literally cut back, with bedrock removed — a change still reflected today in the bend of the West Side Highway. By the 1960s, the complex had fallen into disrepair, and the current terminal at Piers 88–92 was built in the early 1970s.

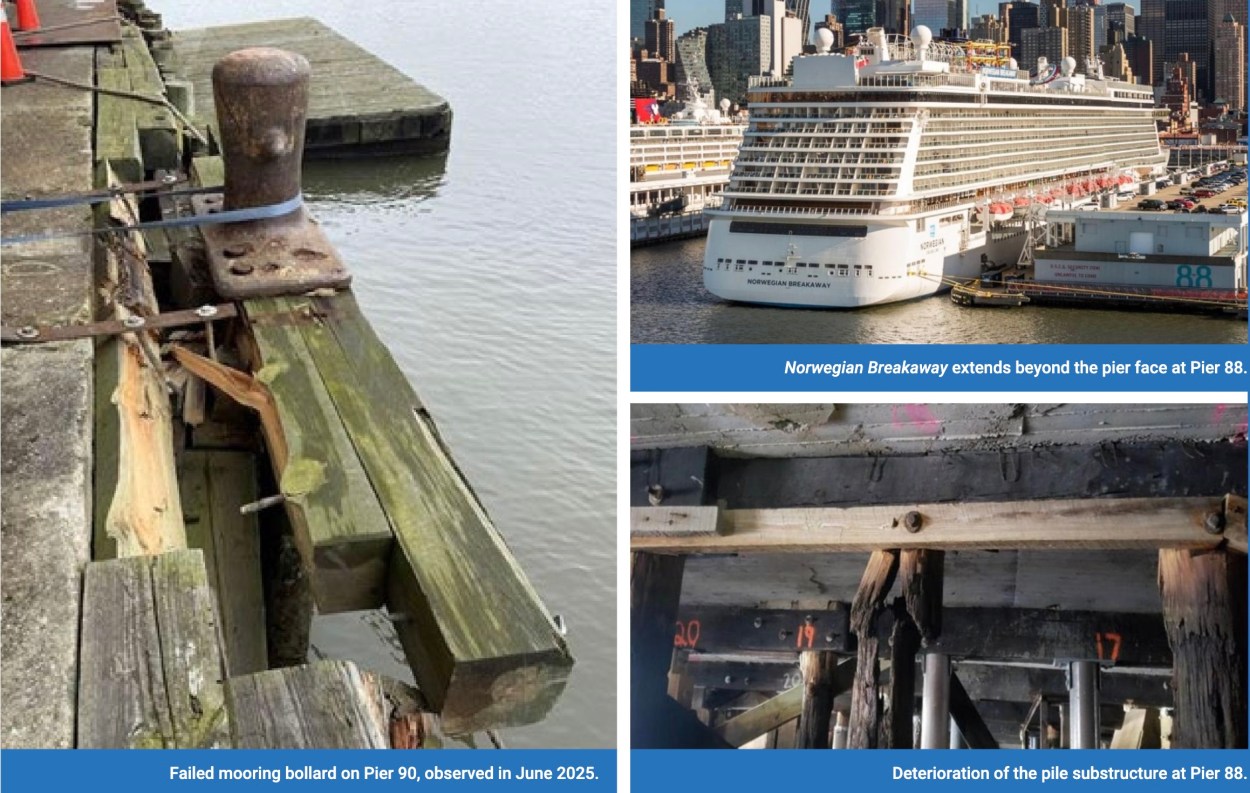

In their Master Plan, EDC shows a failed mooring bollard at Pier 90, which is now inoperable, and deterioration of the pile substructure at Pier 88 (which they now describe as the “workhorse” of the terminal). Photos: EDC

In their Master Plan, EDC shows a failed mooring bollard at Pier 90, which is now inoperable, and deterioration of the pile substructure at Pier 88 (which they now describe as the “workhorse” of the terminal). Photos: EDC

EDC has not set a price tag or timeline for the new project, but at a December meeting, David Lowin, the agency’s senior vice president for development and asset management, described it as “in the billions of dollars” and said it would be financed through a mix of public and private funds.

The Pier 90 shutdown also raises a politically sensitive issue: the Community Fund. Created after years of pressure from MCB4, the fund is financed by $1 per cruise passenger and is intended to compensate Hell’s Kitchen for decades of pollution and disruption caused by the terminal.

Letters approved by the MCB4 board in November 2023 and July 2025 outline EDC’s agreement that any decrease in passengers would be addressed, to prevent the fund from shrinking during transitions. The July 2025 letter states: “Any shortfall in passenger numbers leading to diminished contributions to the fund on an annual basis shall be supplemented, as agreed upon with EDC at the October 2023 WPE meeting.”

In its briefing to W42ST, however, EDC said only that the fund will continue to reflect $1 per passenger, without committing to making up any shortfall caused by reduced traffic while the terminal operates with just one functioning pier.

The Master Plan for the Manhattan Cruise Terminal promises more public access to the waterfront. Rendering: EDC

The Master Plan for the Manhattan Cruise Terminal promises more public access to the waterfront. Rendering: EDC

For some in the neighborhood, the failure of Pier 90 changes the context in which the Master Plan is being evaluated. The proposal asks the federal government to alter a protected navigation channel, asks the city to alienate parkland and asks the community to accept a permanent reshaping of the Hudson River — all before final designs, costs or timelines have been set.

EDC, for its part, argues that this moment is precisely why the project has grown from a series of smaller fixes into a comprehensive plan. “It’s really about trying to be a good neighbor,” Allison Dees told the board, “and also combining that with what makes us a competitive cruise port.”