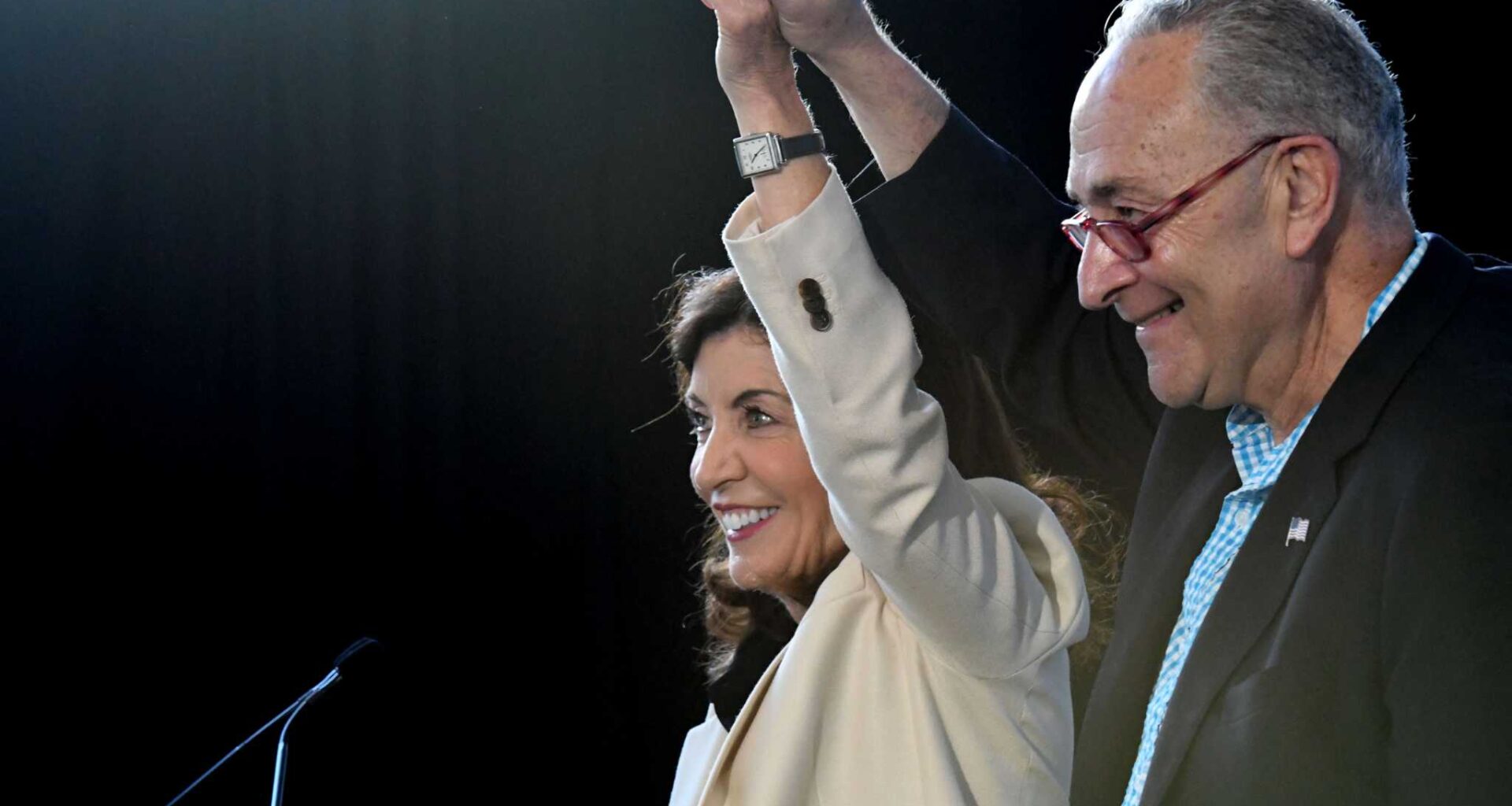

Gov. Kathy Hochul and Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer are strong proponents for taxpayer-funded incentives for semiconductor manufacturing.

Will Waldron/Times Union

State Sen. Liz Krueger was one of only two state senators to oppose costly semiconductor manufacturing legislation.

Lori Van Buren/Times Union

State Budget Director Blake G. Washington hold a key position in Gov. Kathy Hochul’s administration.

Will Waldron/Times Union

The Green CHIPS legislation was passed with no fiscal analysis even though it created billions in publicly funded subsidies.

Will Waldron/Times Union

State Sen. Jeremy Cooney advanced incentives for semiconductor manufacturers on the promise of job creation.

Will Waldron/Times Union

ALBANY — In the final days of the 2022 legislative session, state lawmakers overwhelmingly signed off on a series of multibillion-dollar expenditures they said would position New York as a leader in semiconductor manufacturing.

Despite it being widely understood in the halls of the Capitol that the measures would be enormously costly for taxpayers, the “fiscal implications” section of the bill’s public-facing description read: “TBD.”

Article continues below this ad

So far, “TBD” has meant up to $5.5 billion in taxpayer-funded incentives for Micron to build several large chip fab plants in central New York.

New York lawmakers’ silence on the fiscal implications of such a massive taxpayer expenditure is not unusual for the state. But similar legislation passed in Colorado, Ohio and Kansas that created or expanded incentives for semiconductor manufacturers included a publicly disclosed fiscal estimate before being voted on.

‘Black box’

Fiscal notes are important because they provide “lawmakers and the public alike with a well-rounded analysis of how an introduced bill could impact our state and communities; and that is good policy making,” Colorado House Speaker Julie McCluskie, a Democrat, said in a statement to the Times Union.

Article continues below this ad

Make the Times Union a Preferred Source on Google to see more of our journalism when you search.

Add Preferred Source

New York is one of 12 states that don’t offer public fiscal analyses on all legislation that could potentially impact state revenues or expenditures, according to a Times Union review of legislative practices in 50 states.

A document outlining potential impacts on state revenues or expenditures accompanies most legislative proposals in other states. Both large states, with hefty legislative budgets, and small states, with limited resources, research the potential financial implications and taxpayer benefits of policies.

A bill with any potential financial impacts cannot be proposed in Wyoming without a fiscal note from the Legislative Services Office, a nonpartisan arm of the Legislature. In California, studies include both financial implications and list supporters and opponents of legislation.

Article continues below this ad

“You have to have the revenue sufficient to pay for spending, and the only way you know that is if you’ve studied the costs,” said Josh Goodman, who studies state fiscal management for The Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonpartisan organization focused on improving policy through public research.

When New York lawmakers put forward proposals, they include a “summary of provisions,” a “justification” stating why the bill is important, and a “fiscal implications” section. But, unlike the vast majority of states, those sections are written by partisan legislators, not nonpartisan staff.

“Everyone knows that the memos that accompany bills are a joke,” said Rachael Fauss, senior policy advisor at Reinvent Albany, a good governance group.

One impediment to including robust fiscal notes is the volume of bills introduced every year. More bills are filed in the New York Legislature than in any other state, according to FiscalNote, a government research firm.

New York has the option to skip the analyses for proposals estimated to have minimal financial impacts and require studies for particularly costly measures. Iowa, for example, only requires studies on bills that could cost the state more than $100,000. That figure could be higher in New York, given the state’s size.

Doing so may save the state from implementing expensive policies or making costly allocations without understanding the consequences.

Take the New York Health Act, which would have major financial implications for the creation of a single-payer health system in the state. The bill has just a three-sentence “fiscal implications” section.

“You’re talking about deconstructing the entire health care system of the state, so it’s close to a fifth of the economy, replacing it with something new that would be financed entirely with tax dollars, and it doesn’t have a real fiscal note,” said Bill Hammond, a senior fellow for Health Policy at the Empire Center.

The New York State Health Foundation helped fund a study into the bill’s costs and benefits. RAND, a nonpartisan research organization, found the legislation could reduce health care spending over time. The study was commissioned more than seven years ago, so its findings may not be up to date, Hammond said.

California has also considered single-payer health care policies, but public-facing fiscal notes played a role in tanking them, said Scott Graves, budget director at the California Budget and Policy Center.

“The cost estimates that were done by the Legislature were very sound, and in some cases, were contrary to estimates that were being produced by consultants working for the proponents,” Graves said.

Single-payer health care would cost the state up to $100 billion annually, according to an analysis created by the California Senate Appropriations Committee.

The analysis also details other challenges and potential benefits of universal health care, including needing a sign-off from the federal government.

The juxtaposition of a detailed state analysis with private studies, both supporting and opposing policies, is what’s missing in New York compared to California and other states.

A lack of fiscal notes “hurts the legislative debate and may impact the quality of the legislation,” said Blair Horner, senior policy advisor at The New York Public Interest Research Group.

If only a handful of people at the pinnacle of the legislative process understand policies’ implications, it increases the value of lobbyists who can access that information.

“As long as Albany’s a black box, the people who can argue they’re hot-wired into the system are the people that make the money,” Horner said.

“Information is the currency,” Horner continued, and if the Legislature were to democratize the process, “it’s currency out the door” for powerful special interests.

Paul Francis, former director of budget under then-Gov. Eliot Spitzer, said he understands the hesitancy to make the legislative process more public because “it’s hard to make good policy, even in private.”

Article continues below this ad

But, “in the long run, it’s self-defeating,” Francis continued. “They should put more out, allow more democratization of analysis where smart people can assess the underlying assumptions.”

Foregoing detailed fiscal notes is “irresponsible, and needs to be reformed,” said state Sen. George Borrello, a western New York Republican.

Republican lawmakers say they have staff who study policies for fiscal impacts, but don’t have the resources to thoroughly review every proposal.

‘Balls and strikes’

Without a robust analysis accompanying policies, legislators rely on a confluence of internal research, studies conducted by proponents and opponents of bills, and research from the governor’s office, said Senate Finance Chair Liz Krueger, a Manhattan Democrat.

The lack of public-facing fiscal notes doesn’t create “wasteful spending,” she said.

It’s in the state budget process where Krueger sees issues.

Most years, the most costly legislation and many of the governor’s top priorities end up in the state budget.

Article continues below this ad

They are studied for fiscal implications and fit into a broader process of ensuring the state is not spending more than it can afford.

However, a few issues set New York’s budget process apart from other states.

Gov. Kathy Hochul’s executive budget, which will be unveiled Tuesday, was shaped with the assistance of the Division of Budget. Over the next several months, that spending plan will be finalized through what are usually closed-door negotiations with legislative leaders.

Krueger has long championed a bill to create a Legislative Budget Office to independently study and provide public analysis of the budget. She said it’s necessary so lawmakers and the governor aren’t relying on partisan estimates that reinforce preconceived ideas.

“There’s no one calling financial balls and strikes within the legislative process, and that definitely hurts the financial situation of the state,” Horner said.

It’s important for a nonpartisan agency to study policy because “(with) estimates from the executive branch, there can at least be the perception that a governor’s position could influence the numbers,” said Goodman, the Pew researcher. Most states have a nonpartisan budget office like Krueger is proposing, Goodman noted.

Krueger’s bill, which has been proposed for more than 15 years, didn’t move in the Legislature when Republicans controlled the state Senate until November 2018. It’s also stalled in the years since, even with Democrats in control of both chambers.

“I’ve served under five governors, from both parties, and the asymmetry of both power and information between the Legislature and the governor has always been a problem,” Krueger said.

‘Drop in the bucket’

Sometimes budget policies come with no cost estimate. In 2022, the Legislature passed legislation mandating that by 2027, all new school buses purchased in New York would need to be electric.

The “budget implications” of the policy in the governor’s proposed budget read: “Enactment of this bill is necessary to implement the FY 2023 Executive Budget.”

“This could result in increased reimbursements to districts in future years,” read the Senate Democratic staff analysis of the same policy.

Article continues below this ad

But when California passed similar legislation in 2023, a detailed fiscal analysis found it could cost upwards of $5 billion to convert the state’s school bus fleet.

Even though New York has provided upwards of $500 million to assist school districts, it’s not nearly enough to cover the transition, said Brian Fessler, chief advocacy officer at the New York State School Boards Association.

“It’s a drop in the bucket,” Fessler said.

State officials expected electric and diesel buses to cost the same by 2027, but Fessler said that hasn’t happened.

Article continues below this ad

The Legislature has since given school districts leeway to delay electric bus purchases if they can’t afford them.

Even though most expensive polices are moved in the budget process, there are a few notable examples where that hasn’t been the case. The aforementioned law expanding semiconductor manufacturing was done outside the budget in the final days of that year’s legislative session.

Also, New York’s 2019 Climate Act, which requires billions in spending to meet greenhouse gas emissions and clean energy standards, was also moved outside the budget. It’s “fiscal implications” section reads: “To be determined.”

That lack of information has been one of the top concerns raised by utility companies and business sector leaders, who have cautioned for years that New York has never examined or produced a public estimate of the actual costs for ratepayers of the 2019 legislation.

Article continues below this ad

Last year, Democrats in the Assembly blocked Republican legislation that would have required the Public Service Commission to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of the renewable energy and zero-emission mandates.

The bill would have delayed certain mandates for lower-emission levels for 10 years, and allowed the state Department of Environmental Conservation to “suspend or modify these thresholds should they affect reliable electrical service or increase rates by more than 5 percent.”

And in January 2021, two members of the state’s Climate Action Council — Donna L. DeCarolis, president of the National Fuel Gas Distribution Corp., and Gavin J. Donohue, president of the Independent Power Producers of NY — sent a letter to the co-chairs of that council urging them to authorize a study to determine the short- and long-term costs of the alternative ways being pursued to reduce emissions under the 2019 Climate Act.

“A well-reasoned quantitative analysis of the costs associated with various emissions reduction strategies will be essential in enabling the state’s transition to a decarbonized energy future,” the letter stated.

Article continues below this ad

The letter was also signed by more than 70 business, labor and power industry leaders across New York, but it received no response from the council’s co-chairs or other state leaders.

Without a thorough fiscal analysis, the state can take credit for the effectiveness of policies affecting many sectors without providing detailed evidence.

For instance, New York is claiming to save more than $500 million annually by streamlining a program allowing those on Medicaid to choose their own caregiver.

Previously, over 600 companies handled the payroll for the program. Now, just one company, Public Partnerships LLC, is managing the home-care program for New York.

Article continues below this ad

“Now that we’ve ended the ‘wild west’ of the old system and moved to single fiscal intermediary with strong state oversight, New York can effectively protect (the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Program) for home care users and workers and ensure the program delivers the best results for those who need it,” said Cadence Acquaviva, a state Department of Health spokeswoman.

The Times Union repeatedly asked for a fiscal estimate outlining the savings, but the department would not provide one. In August 2024, the newspaper submitted a Freedom of Information Law Request for an estimate of potential savings and has yet to receive a response.

“The critics, and there were lots of critics, said it wouldn’t save $500 million, but they had nothing really to grab on to, because there was no public disclosure of what that assumption was based on,” said Francis, the former state budget director.

Without a public estimate of a bill’s cost its also gives the governor a readymade way to kill legislation. Every year, Hochul vetoes more than a hundred pieces of legislation, often over cost concerns or because the measures were not negotiated in the state budget. The governor, in turn, often vetoes legislation based on fiscal analyses done by her administration that may not be fully documented or explained in detail.

Article continues below this ad

For example, 18 bills passed in 2025 were killed by a single veto. The legislative package, which would have commissioned studies and also proposed creating various offices across a range of state agencies, was estimated to have cost $30 million, according to the governor, who did not provide detailed estimates for each measure that she rejected.

Fiscal notes revealing even a limited financial impact could bolster advocates’ and lawmakers’ arguments against bill vetoes, said Bill Ferris, AARP New York’s legislative representative. Ferris noted AARP’s longstanding fight to create an office to represent New Yorkers in utility rate increases, which has been vetoed numerous times.

In contrast, roughly one-third of the bills that are considered by budgetary committees in California’s Legislature do not survive, in part, because of concerns that arise when details of the estimated costs are released publicly, according to Chris Micheli, a longtime law professor and lobbyist in Sacramento.

Article continues below this ad

He expressed shock that New York lawmakers — and the public — do not have the same type of information available for legislation that may present serious fiscal consequences for taxpayers.

“Oh my gosh, I don’t know how they could conduct business,” Micheli said.