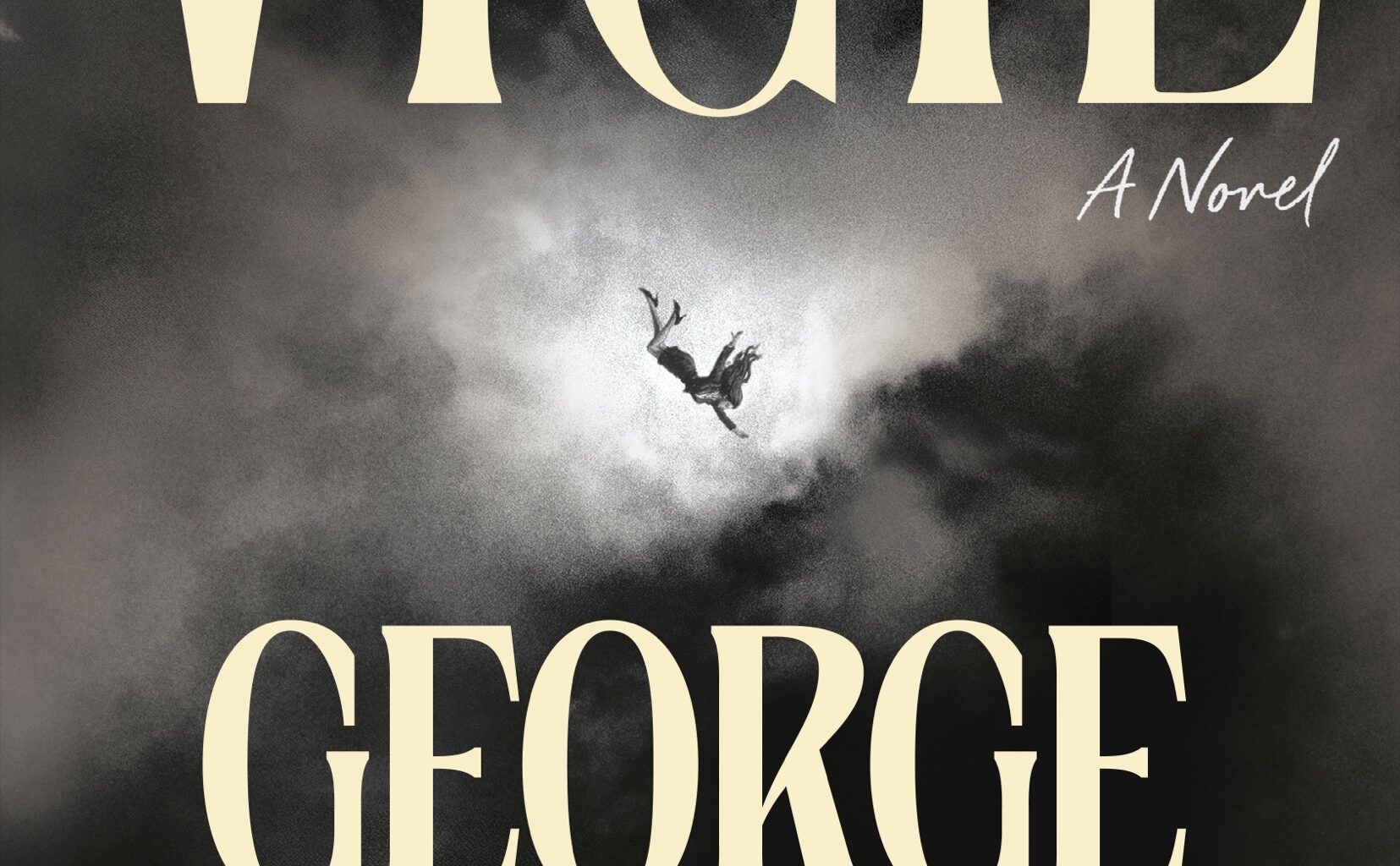

George Saunders

Vigil

Random House, 2026

I could describe George Saunders’s Vigil literally as the final night of K. J. Boone’s life. Boone, a reprehensible oil tycoon—is there any other kind?—source of significant harms to people and the environment, is guided on this journey into the mostly unknown by Jill “Doll” Blaine who is there to provide “comfort, for all else is futility” while other assorted afterlife entities remain prepared to drag unrepentant Boone to the punishment he so richly deserves. Yet that only scratches the surface of this imaginative and open novel that showcases Saunders’s singular ability to craft a supremely human tale that accrues more meaning—and delight—with each chapter.

I was born in a culture that has a deep sense of fate, of what is written on our heads at birth, and have spent most of my life in pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps self-determinism, so I was especially taken by Saunders’s nuanced dance between such seemingly conflicting concepts. It’s also a vibrant contemplation about the value of being a “good” or “bad” person, and whether salvation is possible for the latter, or is a reward for the former. Or whether that even matters at the end, as Jill says early in the novel, “Who else could you have been but exactly who you are?”

We’re all bound by our narratives—those we create for ourselves, and those that others impose upon us—and somewhere within those lines are our lives and legacy. George Saunders’s Vigil is a kind of ars narrationis—the art of narration, if I may be bold enough to create this phrase—consummately plaiting often faulty human perceptions into a novel that examines the subject of storytelling itself, this deeply necessary, essentially human, pursuit.

Mandana Chaffa (Rail): I read that François Rabelais’s last words were “Je m’en vais chercher un grand peut-être; tirez le rideau, la farce est jouée”—or in Peter Anthony Motteux’s translation: “I am going to seek a grand perhaps; draw the curtain, the farce is played”—which feels in kinship with the themes and queries of Vigil. I’m especially taken with that seeking, which can be said about every primary character, dead, alive, or somewhere in the middle. A broad question to start off our conversation, but what were you seeking with this novel? What sparked your imagination?

George Saunders: I’m always seeking the same thing, I think, which is to find a field in which to play—with language, with structure, with humor. I also hope to push out my own boundaries in some way, by trying something that might feel a bit impossible. Once I get working, I love the feeling of seeing something complex coming out of stone. Suddenly, what was just typing is starting to cohere and even somewhat reference things I know from the real world—patterns and tropes and human tendencies start appearing.

Here, the starting point was a kind of thought-experiment: What would the world look like to a person who, in the prime of his life, had been actively complicit in some great act of wrongdoing? And, especially, what would it look like at the end of that person’s life? Any regrets? Might he repent? If so, why hasn’t he done so already? What are the ways in which we (not just he, but we) tend to live in denial? (Why is it that, in life, we take such pains to avoid that “grand perhaps?”)

Although, to be honest, I wasn’t thinking of that at the beginning. That’s what the book decided it wanted to be about. I just started with the thought-experiment. And then it sort of grew organically out from there.

Rail: There’s a subtle and fluid temporality throughout Vigil: even eternity has express and local trains, it seems, country roads and autobahns. It all happens in one (human) night, but within that evening, the temporality shifts both in direction and momentum. Might we talk about how you crafted such intricate elements so that these entities meet, perhaps imperfectly, in these multidimensional moments in time?

Saunders: Well, thank you for all of that. For me, the answer is always: a line at a time. I see a work of fiction as an elaborate call-and-response organism, done over many iterations. So at one point in its text, the book produces a need, and, in re-reading, I notice that and spontaneously address it (or try to), and then, in the next read, it’s an incrementally different book, and I notice a need… and so on. It’s amazing the kinds of unintended-but-then-embraced effects this kind of writing can produce—the book is always teaching you about itself (if you can manage to listen to it). There’s a lot of trust involved, too—just blundering along, making these small choices, in the faith that the book knows what it’s doing. You take your hands off the wheel and the car drives itself, even though it sometimes drives itself into, and then out of, a ditch.

Rail: There’s so much playfulness in this book, George, beyond the weighty concepts of elevation and descension. I was tickled by how Jill joins the narrative in the first pages, inelegantly headfirst into the earth, echoing the Wicked Witch in Oz, though in far more sensible shoes. Or the diversity of ways the Frenchman dramatically appears, disintegrates and re-appears, increasingly frantic and determined. Or the Tweedledee-and-dumness of the Mels. Vigil shares DNA with a long line of epics that use humor to explore existential issues. What were you engaging with artistically while developing this novel?