‘To continue painting’: James Bishop and New York

Timothy Taylor

January 15–February 28, 2026

New York

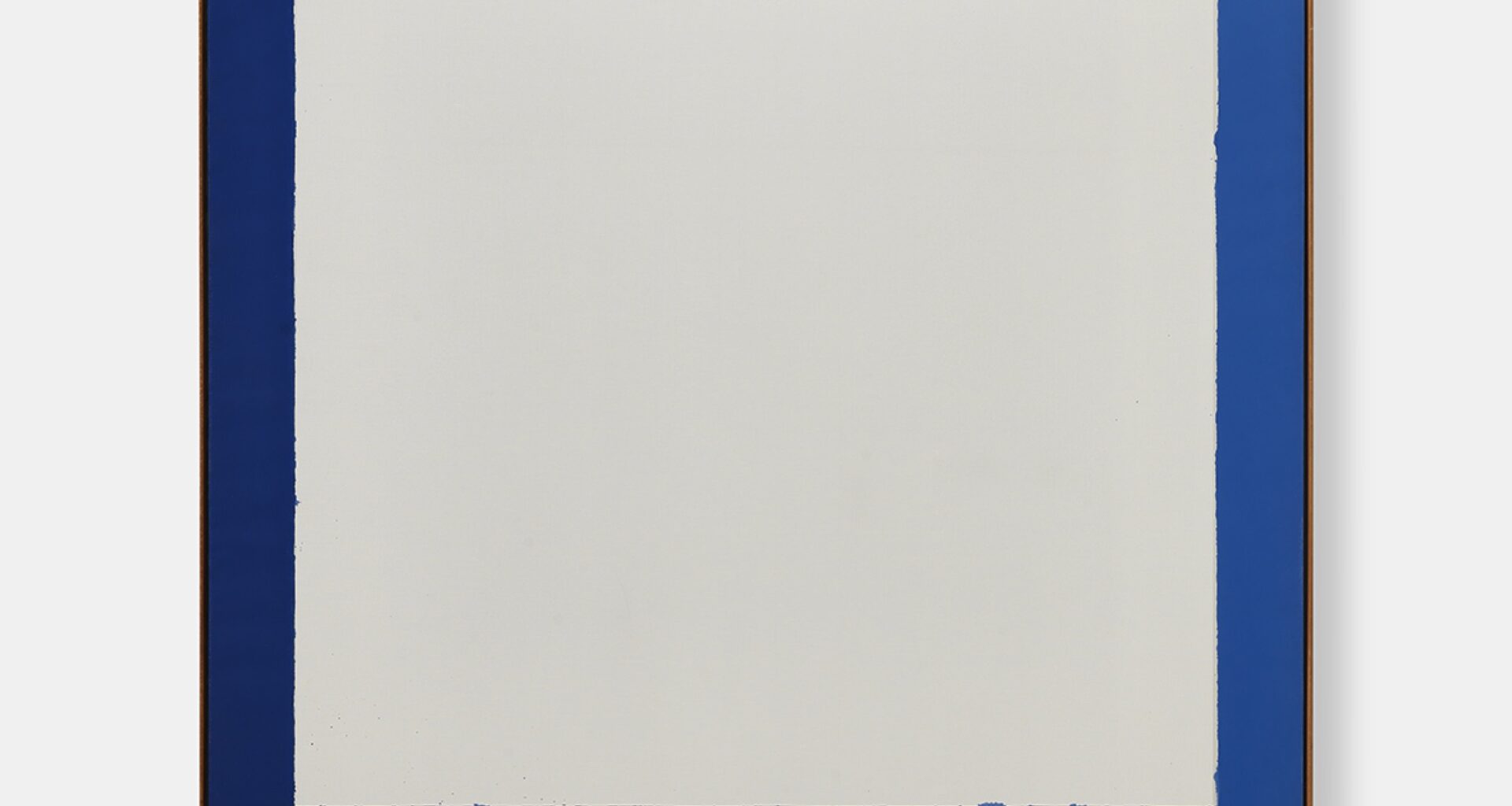

‘To Continue Painting’: James Bishop and New York—eight paintings in oil on canvas and eleven on paper, all made between about 1960 and 1987—is a revelation. Marking the late painter’s first solo exhibition in New York in over a decade, and masterfully curated and hung by Molly Warnock, these works seem to breathe anew in this gallery’s beautifully lit arching spaces. The warm off-white wall color was Bishop’s choice for his exhibitions—he believed, rightly, that off-white walls granted agency to the white of his pre-primed supports, which he often left partially unpainted. Absolutely museum worthy, Warnock’s presentation is a must for anyone seeking to know why painting might matter today.

The works on view present the evolution of Bishop’s practice from the early 1960s, when he lived in Paris (born in Missouri in 1927, he settled in France in 1958), through his brief return to New York in 1966, up to the late 1980s living in Blévy, France. By 1986 he had made his final large canvas before working exclusively on paintings on paper, which he saw as more “personal, subjective, and possibly original,” being written “with the hand rather than with the arm.” Athletic sweeps of the arm, residual gestures from Bishop’s early exposure to Abstract Expressionism, can still be seen in two paintings here, one untitled work from 1961–62 and Hours from 1963. Yet in both, one already notices features of his later work—weathered and tumbled near-geometries, precarious stacking, and the slosh of liquidity that opens variously on to the primed undercoat.

What seemed to intrigue Bishop about a pre-primed canvas was its self-sufficiency; two coats of paint were his limit. Grove Stone (1968), a top/bottom contrast between white and green, is an example: Bishop allows the bright white of the upper register to body forth, balancing its vigor with two rows of four yellow-green quadrilaterals as counterweight in the lower half. Their stacking and contiguity, however, are never secure: the “seams”—Bishop’s term for them—are in constant threat of unraveling through the effects of oscillating densities. Diluting oil paint with turpentine, Bishop brushed color in liquid pools on a canvas laid flat. As he picked up one and then another edge, paint flooded the surface yet remained under his control, at one moment revealing an undercoat, at another covering it completely. Bishop followed this by blotting the edges of the paint, blurring the joins between registers and the elements within them. This semi-aleatory process effected a subtle opening and closing of seams, rather than the sense that delimited contours are merely juxtaposed. As he said, “But all this is interesting only for what it creates in terms of, say, intensities of color, ambiguities of space, etc.”