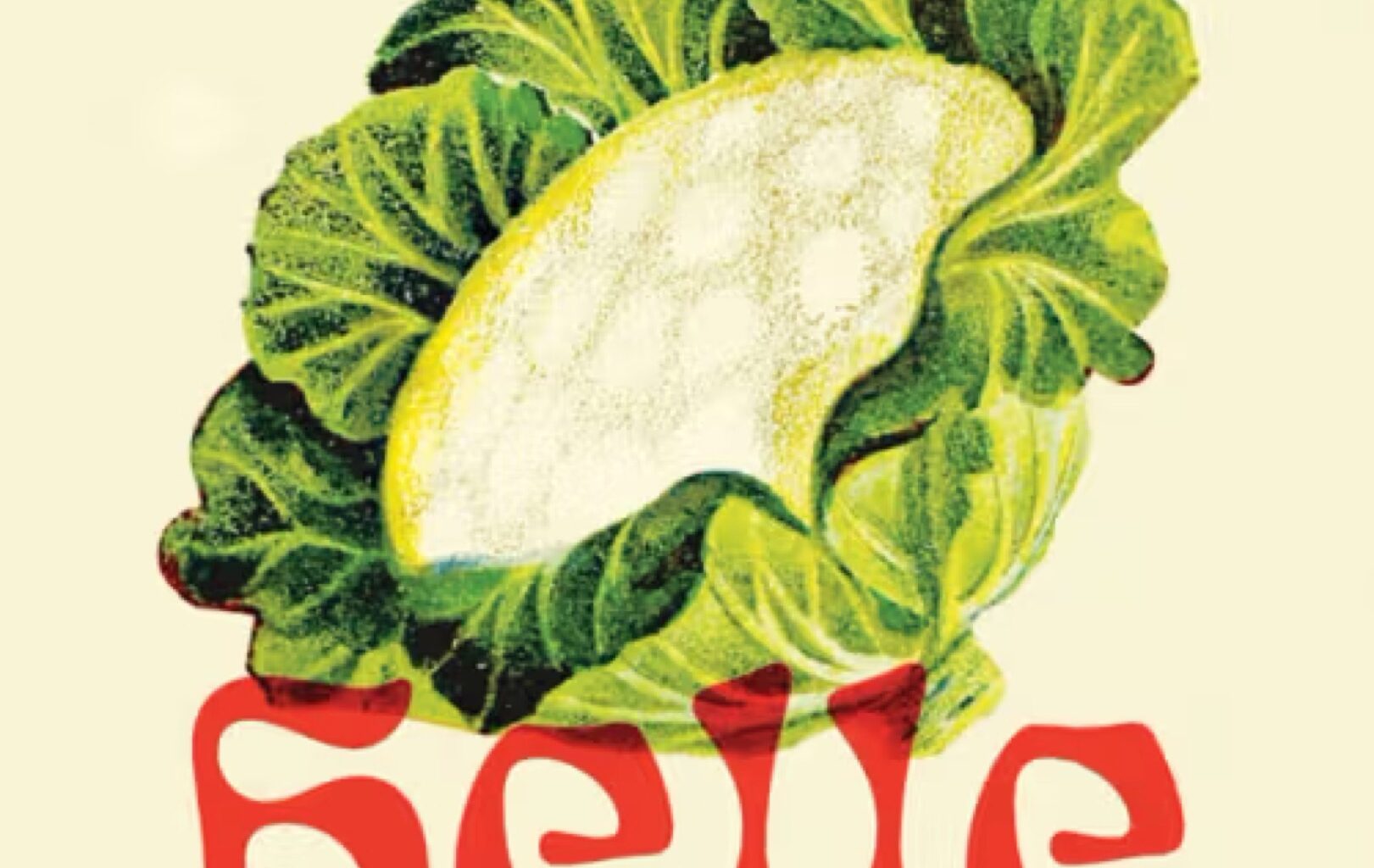

Helle Helle

they

Translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken

New Directions, 2026

They, the titular mother-daughter pair at the heart of Helle Helle’s latest novel, live in a candle-colored apartment above A Cut Above, a hair salon. The trash can full of hair is visible from their window, containing “at one point a complete pair of plaits.” They also live in a succession of other apartments, a single-family home, and a farmhouse. They are always moving. They don’t care for crocuses, but they like crosswords and cauliflower gratin—it is in pursuit of this last that the novel opens, with the daughter walking across a field bearing a giant cauliflower homeward. They are like this, mother and daughter, so close as to share opinions and preferences and certain ways of thinking.

But the mother is dying. “I must,” she remarks, “have swallowed a stone.” It is the daughter, masquerading as the mother on the phone with the doctors, who learns her prognosis first. While she’s on the phone:

Her mother bounds into the living room with two potatoes. She finds a telephone conversation taking place and beats a quiet retreat. Now the music changes, again her mother sings along. The doctors can relieve the symptoms, but the condition can’t be cured. Her school bag is dumped on the floor, she sits in front of it with her back to the rest of the room. Six months, perhaps a year. The dinner’s ready, they can eat now. They eat now.

Eventually, the mother has to go into the hospital, leaving the daughter on her own, though under the friendly if loose supervision of Palle, one of the many charming denizens of their small town (population 2,572). Her mother gives her money, but she decides to spend none of it, leading to what are surely some of the most lovely and loving descriptions of defrosting frozen food to exist in literature. She goes to school, she makes friends with a girl named Tove Dunk, a boy she calls Desert Boots, and others. She does, in other words, the things teenagers do: she rearranges the posters on her bedroom wall, tucks one away in the closet and, “while she’s there, she goes through her clothes. She no longer intends to wear overalls. She experiments with a high ponytail, packs her bag.” She sits at the back of class and “writes a list of things she wants to change about herself. Perhaps she’ll buy a secondhand peacoat, she considers taking up painting too.” She develops minor crushes and makes out with a few different boys in varying states of undress. Life continues in the face of death, in between visits to the hospital, and both are coming between mother and daughter, who never love each other any less but who, because of the separations wrought by illness and by the daughter’s growing up, are becoming more defined. At one point, a friend of the daughter throws a party and the theme keeps changing: first, everyone is to come as who they were, then who they dream of being, and finally, who they are. Many a child found their first costumes in their mother’s closet; the harder task is spending the rest of your life in costume as yourself.