Rail: What about the wallpaper work, Evening Peak Time is Back (2022)?

Kim: That piece is a collaboration with the GL (Girls’ Love) webtoon artist 1172. The long corridor at PS1 felt like the ideal site for it. During my research, I interviewed not only delivery riders but also members of their wider community, and I was surprised to meet this artist—she wasn’t a delivery rider herself, but a highly experienced motorcyclist. She had already created fictional narratives about female delivery riders in one of her webtoons. So we collaborated: she developed characters based on Ernst Mo and En Storm in multiple versions in a recognizable GL comics style, and we set them against environments from our world-building, generated using a game engine. Through layered lighting effects and digital retouching, the work brings research and fiction together.

Rail: Your work engages a wide range of media—video, game engines, AI-generated imagery, virtual environments, and sculptural installation. How did this multi-media language develop, and what does each medium allow you to do that the others can’t?

Kim: I’m very interested in the specificity of each medium, particularly in relation to narrative and agency. I tend to think of my work as time-based media rather than film. Film carries its own historical and institutional traditions, so I usually describe myself as a video or time-based media artist rather than a filmmaker. When Delivery Dancer’s Sphere became a game, for instance, agency shifted to the player: the audience became a first-person experiencing entity. That’s fundamentally different from watching a video.

During the pandemic, I also worked on VRChat, which functioned as a major social gathering space. People met there as avatars, either through VR headsets or on their computers. I created a guided performance in which I acted as a live guide through a fictional world. It operated simultaneously as a lecture-performance and a guided tour. The audience wasn’t simply watching; they were participating inside the fiction. VR produces yet another kind of experience—participants can see their own hands and bodies—but they can also be more passive than in a game, where interaction and choice are constant.

Even when I work from the same narrative backbone, the story inevitably changes depending on the medium. In games, narrative becomes more open and can sometimes flatten, since agency is central. In video, the structure tends to be denser and more tightly controlled. The mode of engagement and the temporality are different.

Because I’m deeply interested in narrative theory, I recently came across a concept that resonated strongly with my practice: metalepsis. It’s a narrative device in which boundaries between fiction and reality are crossed. When I read about it, I realized this is something I’ve been working with intuitively for a long time. In Surisol: POVCR (2021), a VR work, for example, the participant becomes the protagonist, navigating an underwater world and communicating with an AI entity. At certain moments, however, the experience ruptures—the screen goes black, and an uncanny voice interrupts, reminding you that you don’t fully belong to the fiction. The narrative collapses and then resumes. That disorientation—moving in and out of narrative space—is exactly what interests me. Each medium allows me to test these shifts differently, which is why working across media is essential to my practice.

Rail: I’m struck by how closely you engage with emerging technologies. What motivates you to continually learn and work with new tools?

Kim: It’s not easy, but in a way we’re lucky in contemporary art. Unlike the culture industry, we’re not required to chase the newest technology at full speed. There’s always a gap—a delay that allows us to digest technologies and explore possibilities that deviate from purely industrial uses. That gap is important to me.

My background also plays a role. I studied communication design with a focus on motion graphics, so I was already closely connected to contemporary imaging technologies. Later, I studied photography in the UK in a very orthodox, theory-driven context. That training centered on lens-based, optical media, and on the ethical and phenomenological relationship between referent and reference—the indexical link between what exists and what appears in an image.

That relationship has shifted dramatically. With post-optical media—CGI, game engines, virtual cameras—the image is no longer anchored to a physical referent in the same way. A virtual camera replaces the human retina. And now, with generative media, even that logic breaks down. These systems don’t rely on cameras at all, yet they’re already shaping our daily lives.

For me, staying engaged with new technologies isn’t about novelty. It’s about understanding their essential features and parameters—how they transform perception, representation, and experience. Of course, we need to be careful about how these technologies are used and absorbed. But I’m strongly opposed to purely negative responses to technological change. If we want to speak critically about these developments, we first have to understand them.

Rail: What’s your process for working with generative AI? How do you think about control and unpredictability—how far do you allow the system to unfold autonomously?

Kim: At this point, nothing in these systems is fully controllable. I often think of the process like driving: you’re holding the steering wheel, but there’s another, smaller handle you’ve handed over to the AI. Decision-making is shared. Human vision and machine vision have to collaborate. In image making, that condition feels unavoidable—we arrive at decisions together, even though the balance of control is never stable.

Rail: In this context, does the idea of extrapolation play a role in your thinking?

Kim: I use the term primarily in relation to world-building and narrative construction. It’s a term from science fiction writing. When you build a fictional world, you establish a set of conditions—rules, environments, relations between humans and non-humans—and then ask what happens if one of those conditions shifts. What if oxygen slowly disappears? How do bodies adapt? How do social structures change? For me, extrapolation is that speculative, problem-solving pipeline.

Rail: There are often transitions between live-action footage, CGI, and AI-generated imagery in your work. How do you orchestrate those shifts?

Kim: It’s largely intuitive. We usually begin with live-action shooting and game-engine CGI, and we edit those first. At certain moments, I want the image to shift into a completely different aesthetic register. That’s when we use video-to-video AI synthesis. It’s important that the work isn’t entirely generated from scratch—the original footage is still there. For example, in Delivery Dancer’s Arc: 0 °C Receiver, live-action performances were transformed through video-to-video AI processes. We set parameters, work through node-based systems, and gradually convert the material. The result comes from that layered process.

Rail: Looking ahead conceptually, your protagonists, Ernst Mo and En Storm, form an anagram of “monster.” What does monstrosity mean in your work?

Kim: From the beginning, I wanted the narrative itself to function like a labyrinth—through editing, spatial structure, and temporal disjunctions. The protagonists needed to be doubled, to encounter one another in mirrored forms, and even to fall in love. The anagram became a useful device, and from there the idea of the monster emerged naturally. Monstrous figures are often unacceptable to the dominant order, yet they’re also capable of mutation, evolution, and transformation. Monsters, misfits, nonconformists, variants—they’re agents of change. A certain degree of monstrosity is necessary for systems to remain alive and responsive. Ernst Mo and En Storm felt right for that reason.

Rail: Your work is often described as futuristic, but you’ve said it’s really grounded in the present. How do you think about the relationship between the present and the future in your work—and about the idea of futurism that’s often associated with it?

Kim: I think of speculative fiction as a method rather than a genre. Through extrapolation—starting from a specific premise and pushing it slightly beyond the present—reality begins to bend. That distortion creates critical distance. It allows us to see contemporary conditions from an unfamiliar angle, as if viewed from a near future or an alternate present. My work may appear futuristic because of its aesthetics, but it’s fundamentally about the present. I’m responding to existing realities—labor, migration, techno-precarity, geopolitics. The future appears not as a prediction, but as a tool for thinking about what already exists.

That’s why I’m drawn to a range of futurisms—such as Afrofuturism, Indigenous Futurism, and other minor futurisms. They emerge from experiences of disrupted or uneven modernity, contexts in which the present and the past fail to fully accommodate lived realities. In these cases, Futurism becomes a way to reclaim agency by imagining otherwise. In Asian Futurism, this often involves pushing back against techno-orientalism. Western narratives frequently depict Asia as hyper-technological yet depersonalized—figures reduced to replaceable units rather than autonomous subjects. Asian Futurism insists on subjectivity and agency at the center of the narrative. For me, Futurism isn’t about the future itself; it’s a strategy for re-reading the present.

Rail: Where do you find inspiration right now, and what questions feel most urgent for you?

Kim: I read the news constantly. Someone once said that news is the most stimulating product of the twenty-first century, because it exceeds our imagination. It’s hyperreal—sometimes even more fictional than fiction. I’m frightened by it, but also strangely captivated. The sheer volume of stimulus is overwhelming, and that’s often where my ideas begin.

When it comes to the black box of technology, as big tech develops increasingly powerful systems, control becomes more concentrated, and we grow more alienated from the tools we rely on every day. We live inside the technosphere, yet we don’t really understand how it works. That condition—techno-precarity—is something I’m deeply interested in. Paradoxically, it’s also why I want to learn more about technology: to develop literacy.

Rail: You’ve also referenced quantum theory—ideas like many worlds and entanglement. How did that enter your thinking?

Kim: I’ve been reading science fiction for a long time, and quantum theory has been circulating in popular culture for decades. As my work began to involve doubled protagonists—figures who appear as variations of themselves—I became increasingly drawn to ideas like quantum entanglement and possible worlds theory. I was struck by the thought that we might resemble particles moving through the city—easily replaceable, interchangeable. But what happens when two versions of the same being encounter one another? That question stayed with me. My process is slow and cumulative. I’m not someone who builds entire worlds overnight. It’s more like constructing a house: laying foundations, adding structure, and then building gradually, piece by piece.

Rail: This is also where people describe your practice as a kind of “synthetic storytelling,” weaving physics, mythology, and science fiction into intimate narratives. Your doubled characters don’t just coexist—they encounter one another, sometimes even falling in love. How did that narrative logic take shape?

Kim: They are different versions of themselves—parallel others. According to possible worlds theory, there can’t be perfectly identical beings across different worlds. Each version carries its own temporalities, properties, and potentialities. Once you accept that, why shouldn’t they fall in love? That encounter—between another version of oneself—and the possibility of merging, folding into, or collapsing with that other has surfaced repeatedly across my projects. It’s a question I keep returning to.

Rail: That slippage between dimensions becomes especially pronounced in your performance Body^n (2025). For readers, how should we understand that title—and how does the performance relate to the “Delivery Dancer” series?

Kim: Body^n was a title we immediately loved. It was suggested by a researcher-curator at Performa, and naming is always the hardest part. He really understood the context of the work.

The performance grows out of our long engagement with motion-capture technology and from questions that have been developing throughout the “Delivery Dancer” series: otherness, corporeality, and prosthetic agency—what occupies an actor’s avatar, and who performs and controls it. In preparing the piece, I worked with a professional performance researcher to study the history of body doubles, stand-ins, and dance-ins in Hollywood cinema. These figures have always existed—sometimes replacing an actor’s entire body, sometimes substituting for specific parts, sometimes performing stunts. That lineage felt crucial.

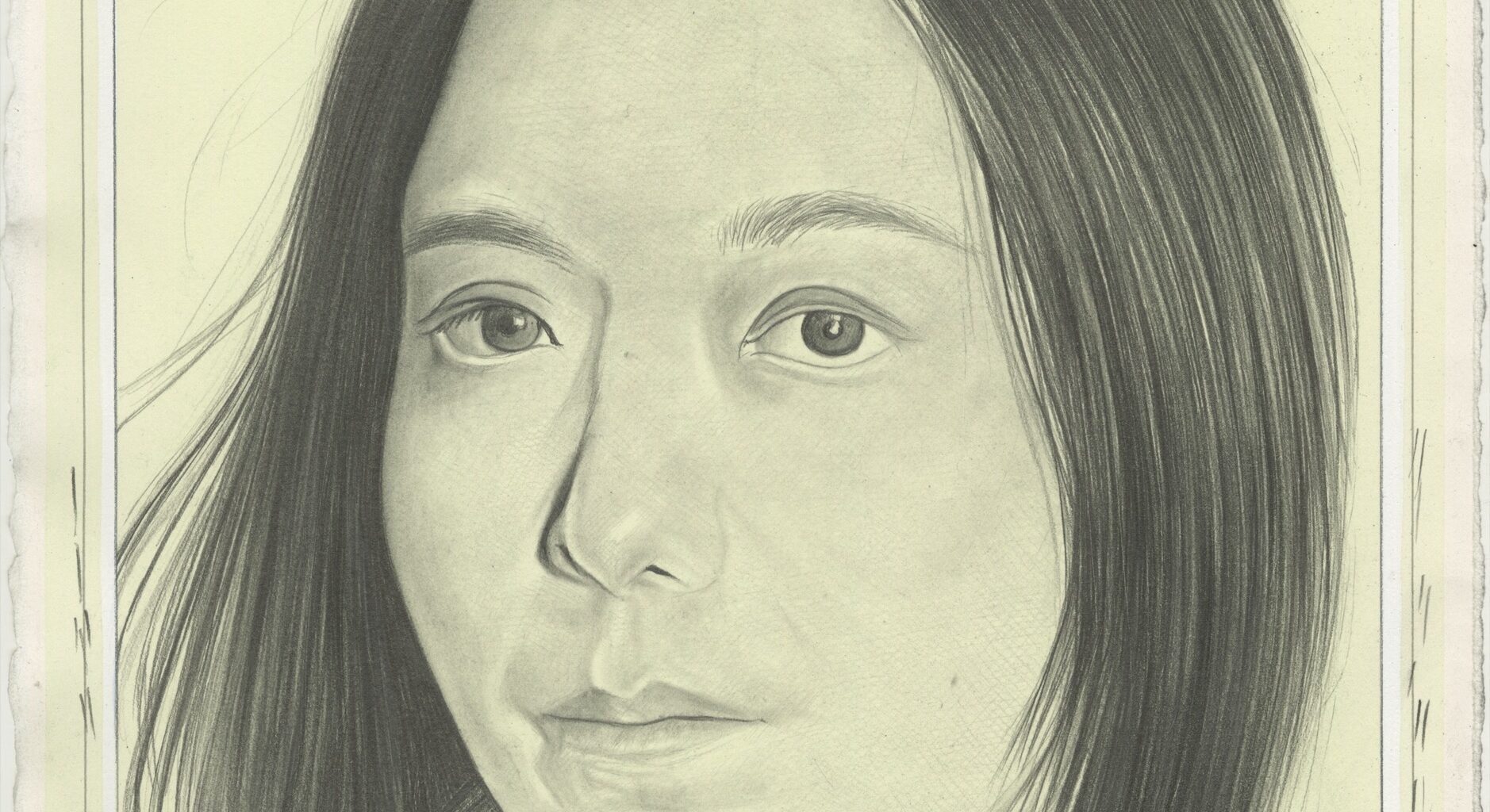

For Ernst Mo, we scanned actor Seokyung Jang’s body and developed a 3D avatar. Over time, it evolved—gaining facial movement, eyes, eyelashes. The body, however, remains hers, while the gestures come from many others. Across the series, there are already multiple body doubles—riders, actors, dancers. In Body^n, that multiplication becomes explicit. At this point, nearly sixteen people contribute to a single avatar.

So whose body is it? Whose movement? Whose agency? The body becomes a shelter, a carrier—almost a stage—where presences appear and disappear. I think of this condition as altered presence: a fragile, unstable mode of being produced through technology.

Rail: Seeing it live felt like a physical extension of your work, very different from the videos.

Kim: Exactly. We also wanted to foreground invisible labor. Motion-capture technology depends on many unseen bodies. It mattered to me that, in this New York iteration, Ernst Mo was performed by women of different ages and physical histories—two Korean stunt performers in their thirties and forties, alongside local New York dancers in their twenties. To create a single character, these bodies coexist across different timelines. That multiplicity is essential.

Rail: What do you look for when casting performers, especially for a piece like this?

Kim: For Body^n, Chai Kim was central. She’s a stunt actor and action choreographer. She’s also deeply interested in female-specific strength and musculature—areas that remain underexplored, especially in Korean action culture. Female-to-female violence, female physical intensity—these are still largely invisible.

Stunt performers move with efficiency and necessity; dancers move through abstraction. I wanted that contrast. Chai choreographed the combat sequences, while Korean contemporary choreographer Soohyun Hwang developed the intimate, emotional exchanges. The local dancers worked with New York-based contemporary choreographer Marie Lloyd Paspe. The choreography became a synthesis of very different bodily logics.

Collaboration was absolutely crucial for this piece. The motion-capture system—the cameras, infrastructure, and technical support—was made possible through the generosity of Onassis ONX and Performa, along with Canyon. Onassis ONX Studio provided more than twenty motion-capture cameras and the full system, but more importantly, they offered trust—the freedom to experiment at this scale. I’m also deeply grateful to RoseLee Goldberg and Defne Ayas, the director and curator who commissioned the work. Their intuition, patience, and trust were remarkable, and that support fundamentally shaped the project.

Rail: One of the most striking moments in the work was when human movement translated into objects—scaffoldings, bicycles, ladders.

Kim: That was one of the most important aspects of the project. For the past two years, we’ve been trying to embed human movements into non-human forms such as objects. Many engineers kept saying it was too complicated—bones don’t match, joints don’t align. But our developer said, “Why not?”

It revealed how many conceptual taboos we carry. Once the barrier became mental rather than technical, things began to open up. When human movement syncs with objects, a strange friction emerges—emotional, uncanny. Some people told me it felt even sadder when love or violence suddenly shifted into objects. I find that very moving.

Rail: It’s where agency seems to slip—no longer fully human, but not fully non-human either. Body^n seems to amplify themes of multiplicity and agency already present in “Delivery Dancer.”

Kim: Yes—multiplicity, altered presence, distributed presence. In performance, those ideas exceed the narrative and become bodily. The body is no longer singular; it becomes a condition shared by many.

Rail: As we come to the end of the interview, how do you situate your work within current debates around AI? You’ve said you’re neither a techno-optimist nor a techno-pessimist.

Kim: I resist binary thinking. There are simply too many dimensions of technology to reduce it to that kind of opposition. Technology feels more like a tree—it grows whether we like it or not. We can’t simply stop it. For instance, image-to-video generative AI became publicly accessible just over a year ago, and now it’s everywhere. The speed is frightening, especially because it fundamentally changes how we perceive the world. It infiltrates our daily lives. So instead of asking how to halt it, I’m more interested in tracing its effects—its impact, alternative uses, and other voices, especially fragile ones. And not only contemporary technologies like GPS: older or ancient technologies—timekeeping systems, astrolabes, sundials—are technologies too. They reshaped how we live, move, and perceive time. We no longer look at the stars; we look at our phones.

Rail: Finally, what’s next for you?

Kim: There are two major new projects underway. One is an ambitious “Delivery Dancer” game—an expanded universe built from everything we’ve developed so far, designed for both online and offline experiences.

The other returns to a much older line of inquiry. My father worked as an architectural engineer in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait for ten years in the 1980s. I’ve been revisiting that history, looking at petroleum politics, modernization, and labor migration in the Gulf and the Red Sea.

This time, the project centers on a real story: a Korean construction worker who unknowingly carried a Middle Eastern parasite back to Korea after eating raw fish in the Red Sea. He became the first documented human host of that parasite. It’s a true story—almost biopunk, but documentary.

Rail: So this isn’t science fiction—it’s reality.

Kim: Exactly. Sometimes reality extrapolates itself.