Rail: You’re right, they’re your neon lights flickering very gently. In any case, looking back now, your admiration of Alhambra’s intricate geometric tiles, ornamental vaultings, and carved stuccoes, with elements of arabesque and calligraphy, is in a way at odds with your appeal to simplicity of form—well, they’re not that simple—and minimal use of color, how would those juxtaposed interests reveal issues of time, space, and emotionality in your painting?

Pagk: I went down to southern Spain and saw the Alhambra in the early nineties, right after my father had died. As he was of Jewish descent, I started getting interested in cosmology in different religions, particularly in Judaism and Islam. The figure wasn’t the center of things, and I became more aware of the concept of infinite space. And gradually I came to see that there exists this infinite space in Mondrian’s work as well.

Rail: Especially with his “Pier and Ocean” series starting in 1914.

Pagk: Exactly and also in his later work. That’s when I got rid of the letter-like forms in my paintings. I felt that they were totemic structures, like figures held within, because that’s where I was coming from: figure within painting, figure floating in painting, standing in paint, contained. So, I decided to remove the painting’s boundaries, and I made a painting called Egyptian Blue (1993), in homage to my father. The title hinted to the Israelites leaving Egypt. And this painting treated space as being infinite, going beyond the painting’s boundaries, opening it to the outside world.

Rail: Yes, and the more Mondrian tried to contain, the greater the form of the painting expanded. His network of verticals and horizontals are ready to extend themselves beyond the edges of the painting and onto the surrounding environment.

Pagk: And Barnett Newman brought it even further with his zips, scale, and color field. Anyway, between 1993 and 1999, I was really trying to deal with those issues. Then by the end of 1999 to 2000, I decided to reintroduce the ideas of perspective and image within the painting. That’s when I started moving away from the non-illusionistic picture plane that I was holding on to, because I found the modernist approach had failures in it, and though they were interesting failures, I didn’t have to abide by them necessarily. I also started to reintroduce the arabesque.

Rail: Well, Matisse explored the arabesque in the mid-1920s onward to welcome intricate, flowing patterns from Islamic art, Byzantine mosaics, and textiles into his compositions to emphasize rhythm, decorative beauty, harmony rather than strict naturalism.

Pagk: Matisse has been a big influence on my painting just as much as Klee. And I also love Rembrandt for both his exuberance and painterly eloquence. Yet at the same time, there’s a weight of emotionality. I was also interested in painters like Robert Ryman, and in how Maurice Merleau-Ponty explored the issues of memory and the perception through the body and eye. All is in the eye of the beholder: you come with your own memory of art before seeing a painting or work of art, and this memory is the start of what you see in it.

Rail: I wonder whether the structure and geometry of Richard Diebenkorn’s landmark “Ocean Park” series—which is abstractly visible as landscape divisions, windows, architectural elements, and above all the light of Santa Monica when he moved there in 1967—ever came across your thinking with similar concerns?

Pagk: As much as I love Diebenkorn’s “Ocean Park” series, especially as we share an interest in Matisse, my line and structure come more out of Matisse’s than his. Partly I think Diebenkorn is abstracting reality, whereas I play with the illusion of reality to break through the surface and ultimately come back to the surface to create pictorial depth and an ambiguous space where the viewer may imagine seeing something but always comes back to the painting as an object.

Rail: That’s true. In any case, when did you begin grinding your own color pigment? What prompted you to undertake such a laborious process? And how would you describe its sustaining effects on your painting surface as well as your specific color composition as you often describe it as such?

Pagk: When I left art school in 1982 and had no money, it was cheaper to buy pigments than expensive paints. That was when I started to use pigments. I first used them in a vinyl medium for two years after which I decided to go back to oils and started to grind them with oil. At that time, it was for financial reasons. From there I began to understand that each color also had a pigment quality, not only a color quality—but some were also smooth, some had tooth with pigment particles, some absorbed more oil and so on…and a color became a decision as it was a commitment to grind it. I began to invest in searching for colors in different pigment stores. For example, there would be a bigger choice of cadmium yellows, or ultramarine blues, cobalt, the choice of different colors became vast. I learnt how a color changed in the oil and I learnt about its innate consistency. Each pigment has its own surface when applied. I found colors that one could not necessarily find in commercial oil paint brands. When grinding pigments, I limit myself to grind one or two batches at a time, one for the large areas and one for the lines (sometimes I will use more than one color in the lines). Both of those colors change during the painting process by grinding different colors into them. Thus, infinite hues can be found.

Rail: That makes perfect sense for how the surface appears the way it does, I mean each has its own surface condition. For example, in 8 Squares (2023) how the uneven patches of dried (matte) and wet (glossy) interact with each other on a thickly painted surface otherwise. Can you share with us how such surface appearance came about?

Pagk: The painting started with the eight squares interlinked with lines. I realized I needed to introduce a second structure in the painting like two bodies coming together, like tango dancers, to subvert the viewer from the first eight form structure, giving ambiguity and complexity. At the same time, I worked on the cobalt violet light surface. Cobalt violet light doesn’t have much covering power, because it is extremely translucent and the color changes significantly each time a new layer is added. The surface developed a physical presence; it became more than a color. I spent a couple of months building up the surface, reapplying the same color. At one point, I even added a little red to subvert the blue in the violet. The uneven patches of matte and glossy surface is an ongoing process: it will become more matte over time, and it is apparent only under certain light. I like its living surface and imperfection against the refined lines.

Rail: At any rate, can floating forms, or say suspended geometry, be capable of evoking both movement and stillness at the same time?

Pagk: For me, everything in the canvas has the same importance. Nothing should be left unthought of, even the memory of the past of the painting must be addressed. And that’s where the whole is an absolute. I don’t want to use the word absolute, because that’s not the word, but it’s a unity of things I aspire to see. There are two types of painters: one who already knows how the painting is going to look when it’s finished, and one who doesn’t. I’m one who doesn’t. [Laughs] Every time I bring in a new color, I always feel it can be a total failure, a pictorial failure. The biggest challenge is to create a desirable color composition on which the eye may travel with ease and engagement. To answer your question: like most painters, I aspire to create a dynamic pictorial equilibrium in my painting, where every issue regarding form, matter, color, and composition is equally considered to generate both movement and stillness. This is the most difficult because ultimately it is about trusting oneself on the decisions one makes, but then each painting has its own life, which you have to accept.

Rail: Which again relates to the most essential issue of speed of execution, how fast or slow the artist’s hand gesture can be in coordination or harmony with their natural body movement. This is the very reason why we can detect any form of forgery, be it a painting or a signature once it’s closely examined by those who have sensitive yet discriminating eyes. I suppose such an idea of what was called connoisseurship (explored by Dr. Giovanni Morelli in the late nineteenth century, who introduced systematic visual analysis, and popularized by Bernard Berenson at the turn of the twentieth century) no longer has its similar relevance today. Since we’re talking about speed of execution, I may as well ask you to share with us the relationship between your drawing and your painting?

Pagk: For me, drawing is about the directness and spontaneity of how an image is given birth to, although sometimes I revisit my drawings. My drawings are not studies for my paintings but a parallel expression with my painting. My painting may reverberate into my drawing, and my drawing may echo into my painting. One drawing breeds the other, and over time they may slip an element into a painting. For me, paper is a transparent infinite space, and it only becomes a drawing when the paper is drawn on, while a painting, due to its object nature, is a painting even before it is painted on.

Rail: Drawing is like taking notes of a thought, which requires no specific coherence, whereas painting is like the writing that needs some form of legibility.

Pagk: I agree. But I also want the feeling in the drawing to be monumental and painting to be intimate.

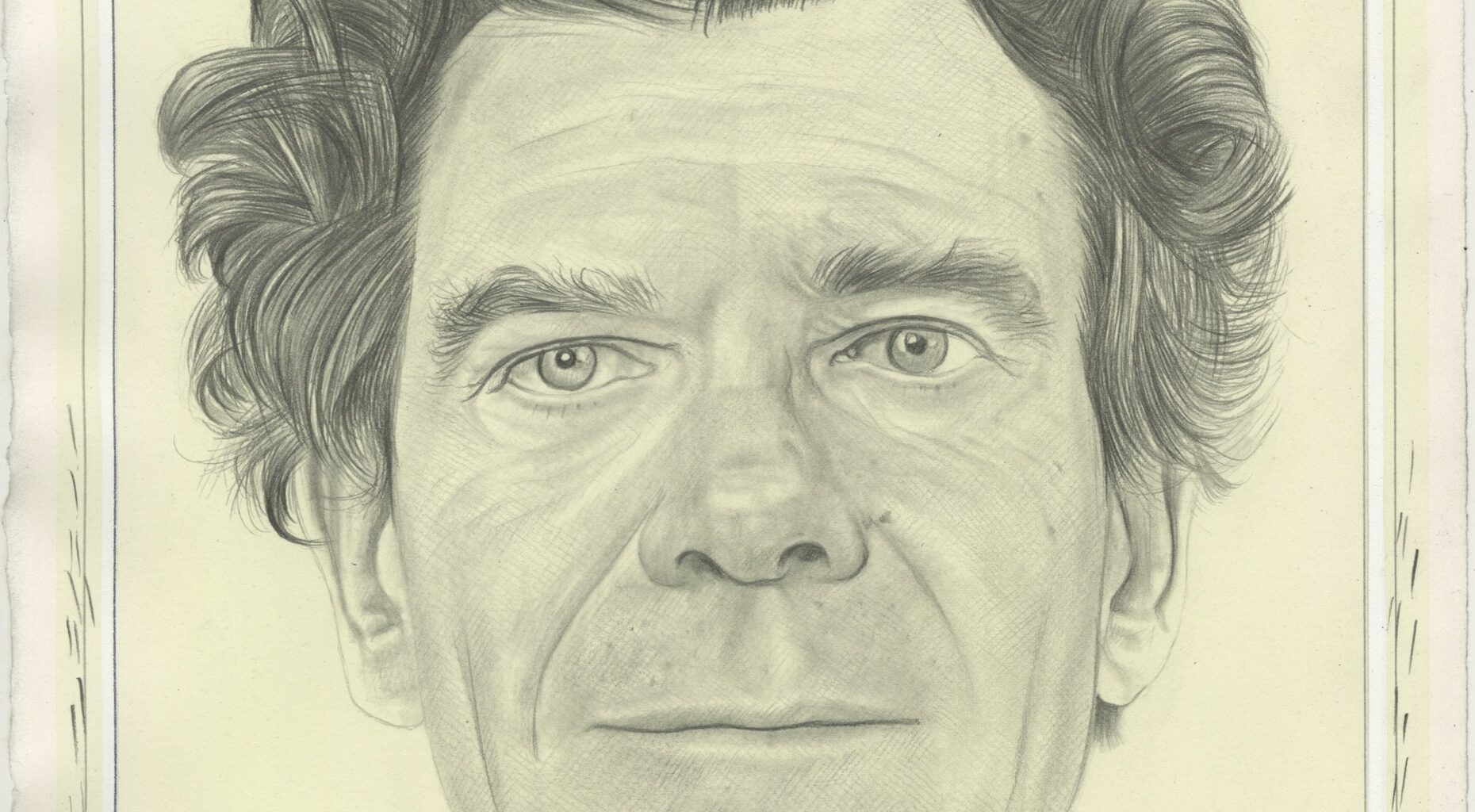

Rail: I thought another interesting thing that Adrian pointed out in his essay was how you took the initials of your birth name, Paul Alexander Godfrey Klein, to invent your last name: Pagk. I thought it was very perceptive of Adrian to suggest that in creating a new identity, a new birth, the four letters P, A, G, K correspond to the four corners or the four edges of the painting. Again, it recalls the four corners of the stage’s proscenium when you were dancing in your youth. Am I over psychoanalyzing this reference to your spatial sense of scale?

Pagk: Yes, for me, the four letters in my surname and in my name are like the four edges and four corners of a painting. I’ve always felt that creating a scaffolding on the painting through the process of drawing is like a skeleton from which the flesh and skin can be built onto. It can take a long time or a short time, depending how the overall image sits in the picture plane. I think scale is not about size. It can’t be measured by mathematical equations; rather it’s an inner or lived condition, as Merleau-Ponty explored — our perception, emotion, memory, and bodies are what lead to each of our personal, sensory experiences. Similarly, color is essential to eliciting this lived experience. I have read Ludwig Wittgenstein’s primary work on color Remarks on Colour—which had a big impact on my way of thinking about color—often think of Goethe’s Theory of Colors, and I was really interested in Isaac Newton’s color experimentations. And of course, Albers’s Interaction of Color confirmed that when you put one color next to another one, say an orange to a red, it will be affected by one another; it’s as if a new unnamable color would emerge. I came to understand color through the color pigments I use to make my oil paint.. Color, for me, is an essential element that can only be expressed through material experimentation; a hands-on experience. I do not use tape, my lines are hand drawn, my paint is hand made. Painting is the ultimate analog art form to be experienced in person, body and mind. I’ve always embraced the idea of imperfection in art: the concept of imperfection as the step after perfection, in a line or a gesture, a surface, revealing my sensibility, my vulnerability, ultimately humanity.