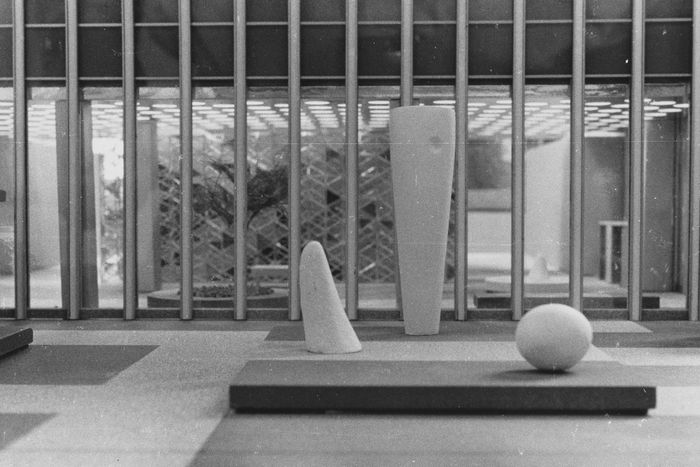

Lever House Sculpture Garden (1952): Noguchi was close with Gordon Bunshaft, lead architect at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and designer of Lever House on Park Avenue. The sculpture garden Noguchi proposed for its sheltered street-level space—twice, in different versions—never came together.

Photo: Charles Uht

A

s a young adult, Isamu Noguchi called himself a citizen of the world. He was born in Los Angeles, reared part time in several Japanese cities, and educated in Indiana, and he voluntarily lived in an Arizona internment camp during the war. Much of his adulthood was spent in New York and Paris and Japan and traveling to the site of some new project, whether in Seattle or Bologna or Mexico City. As an old man, though, he decided otherwise. “I’m really a New Yorker,” he said. “Not Japanese, not a citizen of the world, just a New Yorker who goes wandering around, like many New Yorkers.” And really, what other city’s culture could contain his range and eclecticism? He carved Pentelic marble, same as Praxiteles, but also created sculptures from aluminum plate and play structures from concrete and lamps from mulberry paper. He made ceramics, landscapes, sets for dance performances, Bakelite shells for electronics, the famous biomorphic table, even hats. You can sit and contemplate in his public spaces all over the world: the UNESCO garden in Paris, the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden in Jerusalem, a public fountain in Detroit.

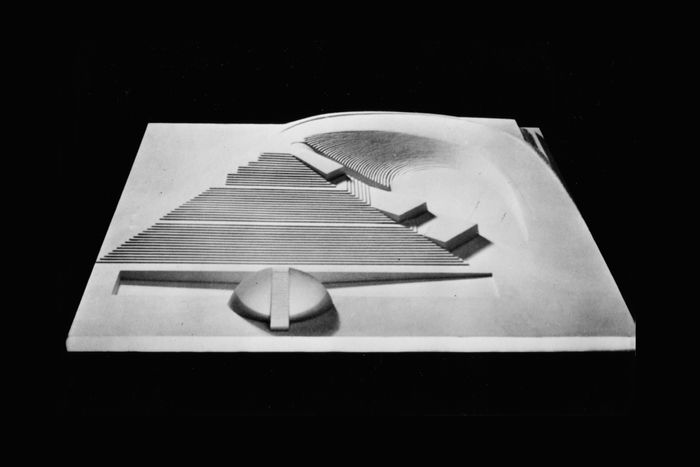

But hardly any are here. Over and over, his city of choice turned him down. His first proposal for a major public work, titled Play Mountain, was a playground that looked like a Surrealist amphitheater cut into the earth or maybe a distant precursor to the land art of Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer. It was supposed to be a discrete module that “could go on any block,” the curator Kate Wiener says — and Noguchi was proud enough of it that he eventually had the plaster model cast in bronze. In 1934, he presented his plan to New York’s commissioner of Parks, the hardheaded Robert Moses, who (in Noguchi’s telling) laughed the artist out of his office. Moses wanted something well-tested and familiar; this weird avant-garde moon base was out of the question.

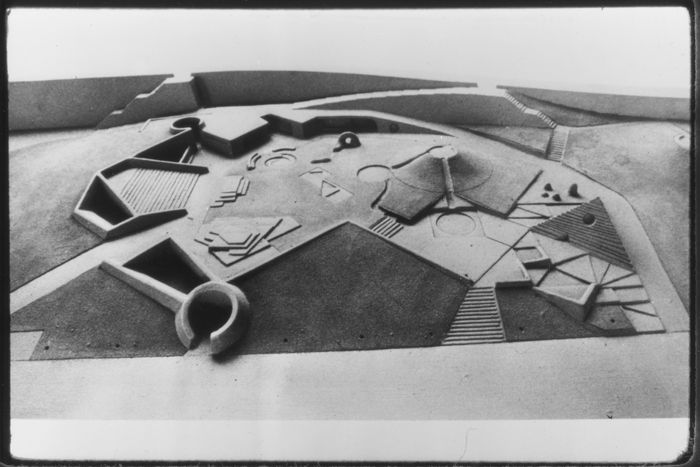

’Play Mountain,’ 1933: Noguchi’s first big proposal for a public space was this playground, with bandshell, sunken fountain, and earthen climbing ramp with public rooms buried below. Intended for any square block, it was far too avant-garde for Robert Moses, who rejected it with a laugh.

Photo: Isamu Noguchi

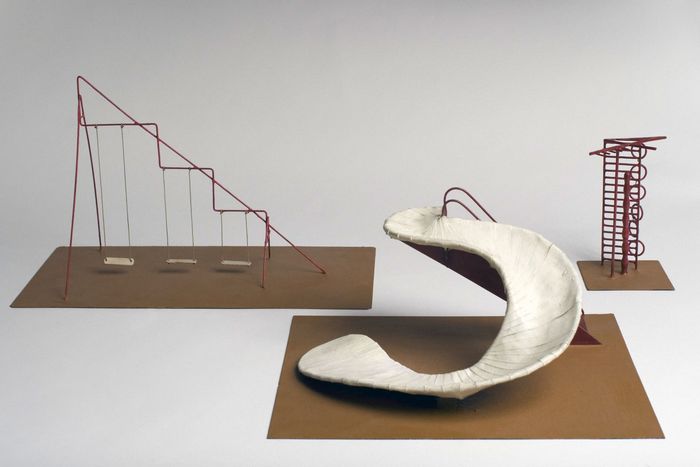

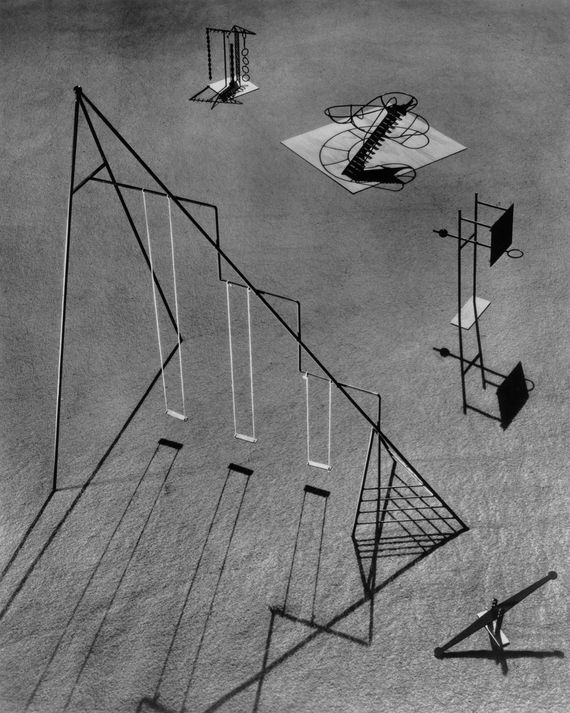

Playground Equipment, 1940: These antic designs — seen here in handmade models just a few inches long — were created for a Hawaii project, then pitched to New York City and rejected. A version of the swings finally went up in Atlanta in 1975. From left: Photo: Kevin NoblePhoto: F.S. Lincoln

Playground Equipment, 1940: These antic designs — seen here in handmade models just a few inches long — were created for a Hawaii project, then pitche… more

Playground Equipment, 1940: These antic designs — seen here in handmade models just a few inches long — were created for a Hawaii project, then pitched to New York City and rejected. A version of the swings finally went up in Atlanta in 1975. From top: Photo: Kevin NoblePhoto: F.S. Lincoln

That bronze casting is one of the first things you encounter at “Noguchi’s New York,” the exhibition just opened at the Isamu Noguchi Museum, which occupies the sculptor’s former studio complex in Astoria. (More proof that he was a real New Yorker: In 1961, he got priced out of his workshop in Greenwich Village and moved to Queens.) As Wiener, the show’s curator, walks me through, her narration inevitably turns into a litany of the artist’s almosts, misfires, and losses. A sculpture installation planned for the Lever House plaza fell through, was revised, then fell through again. A similar sculpture garden, across the street, would have complemented a skyscraper that never got built. An offer to design gorilla environments for the Bronx Zoo came to nothing. A project for Idlewild (now JFK) Airport went to Alexander Calder instead. Another sculpture garden was for the Museum of Modern Art; Philip Johnson got that gig. Still another playground, for the U.N. grounds, stalled as well, once more scotched by Moses. The commissioner hated that one so much that he issued what amounted to a threat of homicide: If it were built to Noguchi’s plan, Moses said, he would omit the safety railings along its edge, allowing users to plunge into the East River. Most of these projects would have been better than what ultimately took their place (though that Calder is pretty great too).

‘Composition for Idlewild Airport,’ 1956: Noguchi offered this proposal in a sculpture competition for the International Arrivals Building at what was soon to become Kennedy International Airport. (Separately, he once proposed an artwork for Newark that was meant to be appreciated only from the air.) Alexander Calder got the JFK job instead, and his mobile Flight now hangs in the IAB’s successor.

Photo: Isamu Noguchi

Even when he did get something built, it often didn’t stick. A big industrial-realist piece outside the Ford Motor Company’s pavilion at the 1939–1940 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows was demolished after the exhibition ended. A sharp-edged hanging sculpture in the Bank of Tokyo’s lobby at 100 Broadway, installed in 1975, was cut up and removed five years later because it intimidated visitors. His lobby for 666 Fifth Avenue, a swoopy ceiling installation that met a waterfall along the back wall, was gradually compromised by renovations and then, in 2020, removed completely. He didn’t see a piece of his work permanently placed on New York City land until he was 75, when a big stone sculpture went up at the southeast corner of Central Park. It has since been moved uptown, next to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

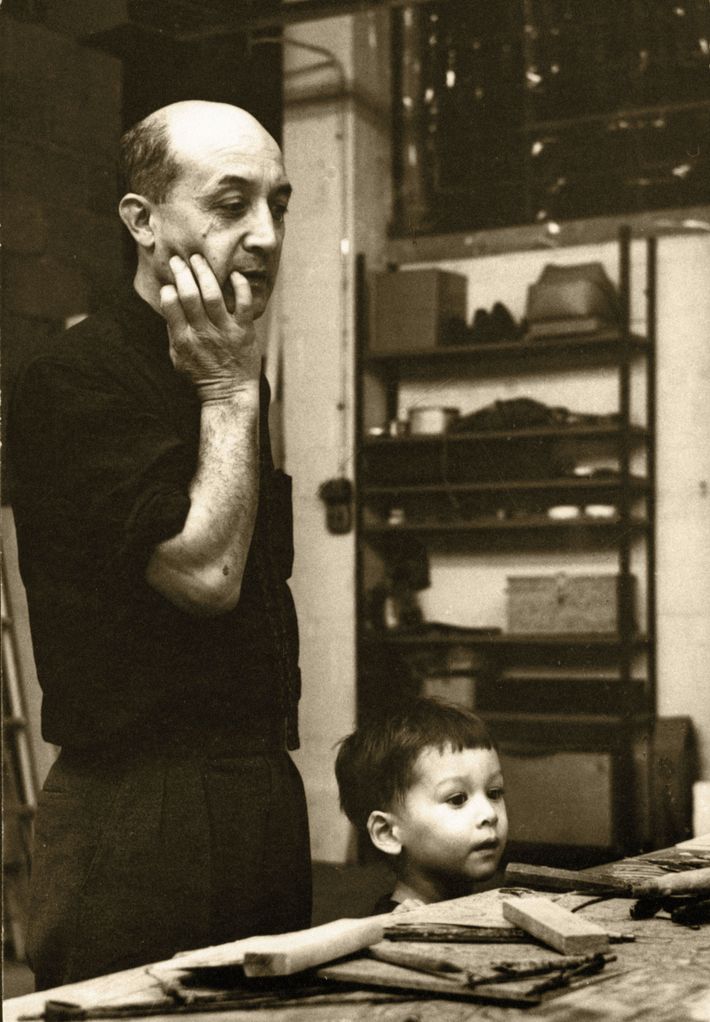

Isamu Noguchi and friend consider his Riverside Park playground design, 1961.

Photo: Ruiko Yoshida

Probably his biggest failure to launch was in Riverside Park. There, his scheme for the Adele R. Levy Memorial Playground drew on some of the Play Mountain ideas, but it was a far more fully thought-through design made in collaboration with Louis Kahn, Yale’s great bard of concrete. It would have reached from West 101st to 105th Streets along the river, and it nearly did come to fruition. A donor was ready to pay for a lot of it, and by then Moses had retired. Kahn and Noguchi softened its edges to make concessions to the neighborhood, and there were enough supporters to fight the usual community pushback. (Some of which, Noguchi believed, was owed to racist concerns that the playground would draw Harlem kids down to the Upper West Side.) Kahn and Noguchi managed to get four-plus years into the planning process—only to have a new mayor, John Lindsay, kill it off. Later, Noguchi said of the city’s Parks Department, “I have no use for them whatsoever.”

Riverside Park, 1961–1965: Five years in the planning, Noguchi and Louis Kahn’s vision for a big play space between West 101st and 105th Streets was divisive, with fierce support meeting similarly fierce opposition. After many compromises, it was just about to break ground when incoming mayor John Lindsay scratched it.

Photo: Isamu Noguchi

Astor Plaza, 1956: Vincent Astor, in the mid-1950s, planned a 46-story skyscraper right across Park Avenue from Lever House — it was even supposed to have a helipad — and asked Noguchi to design the ground-level public space. Neither got built; the tower that did go up there, in 1961, doesn’t have much of a plaza.

Photo: Isamu Noguchi

You can get a little rueful about all of that, but a Noguchi New York walking tour is at least easy to schedule: that sculpture outside the Met, the stainless-steel relief over the entrance to 50 Rockefeller Plaza, and the big red cube and fountain at Chase Manhattan Plaza. None of these quite conveys his big ambitions except the Noguchi Museum itself. “When he opened this institution,” Wiener tells me, “he felt like he had finally outsmarted Moses.” Yet another familiar New York experience: The way to preserve anything you care about, whether it’s a restaurant or an artistic legacy, is to buy the real estate.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the February 9, 2026, issue of

New York Magazine.

Production Credits

Photographs:

© The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum New York/ARS

Related