The New York City subway began service on October 27, 1904, originally operating between City Hall in downtown Manhattan and 145th Street and Broadway in Harlem. In the 121 years since its debut, the city’s network of trains and stations has grown into one of the largest rapid transit systems in the world. But this was not the city’s first attempt at an underground transit. Often a footnote in the city’s transportation history, the first underground train to serve New Yorkers was a once-secret, 312-foot line beneath Warren and Murray streets in Lower Manhattan, known as the Beach Pneumatic Transit.

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, New York City had a notorious traffic problem. The city’s growing population and lack of traffic regulations turned Broadway, the city’s main thoroughfare, into a constant tangle of people, horses, wagons and carriages. An 1856 essay attributed to the poet Walt Whitman,colorfully described a typical Broadway traffic jam as: “[the] tramp of the horses, the voices of the drivers, the rattle of wheels, the confusion, stoppages, expletives, excitement, are such as only Broadway can exhibit.”

As early as 1832, New Yorkers seeking to solve the Broadway congestion problem proposed operating an elevated railroad. However, omnibus companies (which operated enlarged horse-drawn passenger carriages) and Broadway property owners, fearing a loss of business, quickly shut down any such plans.

The condition of New York’s streets caught the attention of Alfred Ely Beach, the editor-publisher of the science journal “Scientific American.” Ever the inventor, Beach proposed his first solution to Broadway’s traffic problem in 1849, suggesting the city run a horse-drawn subway under the street. While this proposal didn’t gain much traction, the rejection didn’t stop Beach’s interest in alternative transit.

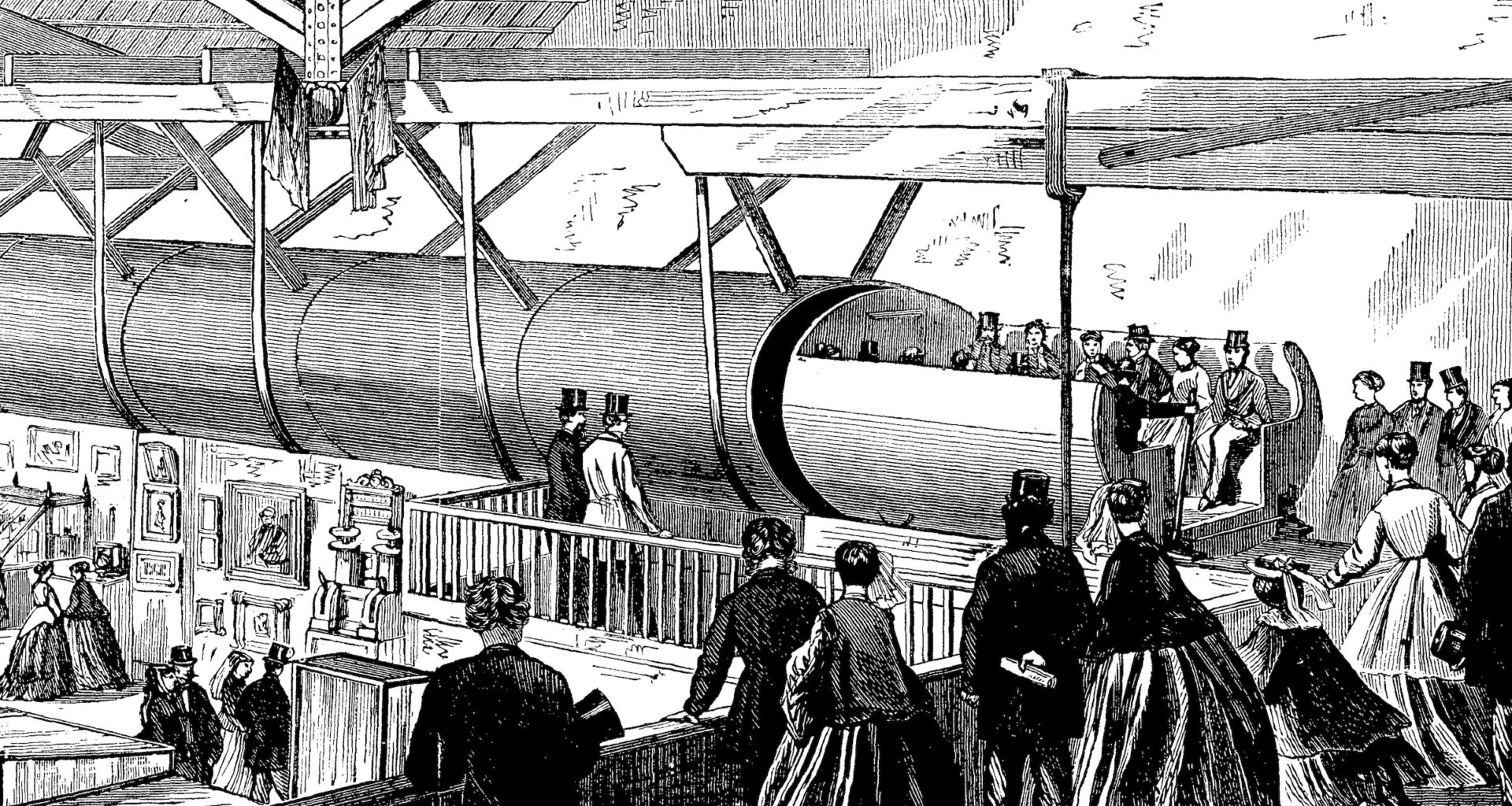

Inspiration came in the form of pneumatics, or the use of compressed air to move objects. Beach was fascinated by the use of narrow pneumatic mail tubes in London. But, instead of using tubes to transport letters and packages, he sought to use the technology to move people. Seeking to stir public interest in this new venture, at the 1867 American Institute Fair he unveiled an above-ground passenger pneumatic tube. Fairgoers marveled at Beach’s innovation, and by the end of the fair, more than 75,000 passengers took a ride on the pneumatic tube, finding it a major advancement in a world driven by steam and horsepower.

Beach envisioned a passenger pneumatic tube running the length of the city and ending at Central Park. But before Beach could begin construction on his grand enterprise, he faced opposition from the influential political leader (and notoriously corrupt) William M. “Boss” Tweed. Tweed refused to grant Beach a charter, knowing a pneumatic subway would lose him profit from potential elevated railroad agreements. So, Beach went back to the drawing board and returned with a proposal to build a pneumatic “mail” tube, which received approval.

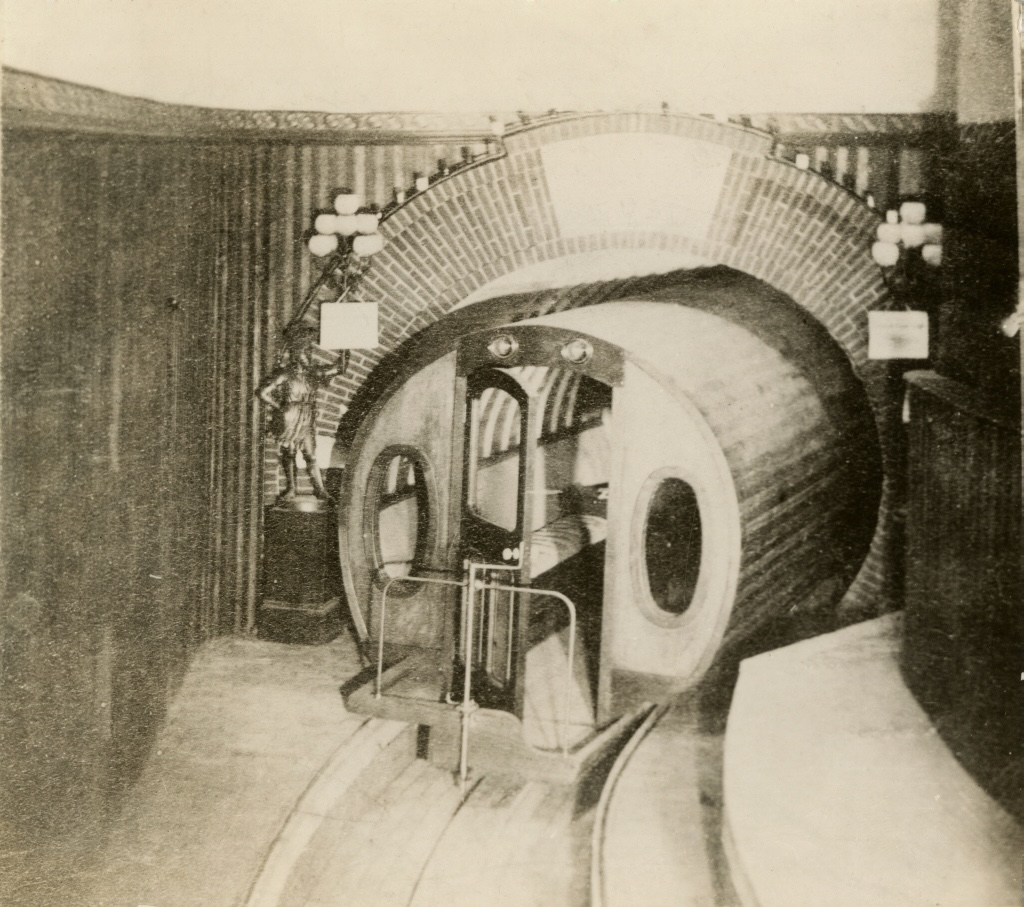

Unbeknownst to Tweed, though, the mail tube was a ruse, and Beach was secretly constructing a prototype subway. Beach knew constructing a miles-long subway line wasn’t feasible, and settled for building a prototype, hoping to capture the interest of New Yorkers while bypassing Tweed. At night, from the basement of Devlin & Co. clothing store on Murray Street and Broadway — just across the street from the Tweed-controlled City Hall — Beach and his men built the city’s first subway. It took only 58 days.

By Unknown photographer – New York Historical Society, Bildnummer 70265, Public Domain

By Unknown photographer – New York Historical Society, Bildnummer 70265, Public Domain

Beach Pneumatic Transit opened in February 1870 to a surprised but delighted public. Beach’s new subway station was opulent, featuring frescoed walls, a fish tank and a fountain. The New York Times reported at the time: “ [Those] expected to find a dismal, cavernous retreat under Broadway opened their eyes at the elegant reception room, the light, airy tunnel and the general appearance of taste and comfort in all the apartments.” Powered by a single, large fan, the new pneumatic subway became an instant attraction. An estimated 1,000 people per day paid 25 cents to descend below the city for a thrilling 312-foot ride between Murray and Warren streets.

In the year following the subway’s opening, Beach faced political pushback from Tweed. However, as the political landscape shifted, the state legislature granted him approval to proceed with his subway project in 1873. But despite this legal victory, Beach Pneumatic Transit ended operations the same year. The Financial Panic of 1873 caused shock waves throughout the country, and investors immediately withdrew support from Beach’s subway. The once-celebrated pneumatic subway station was rented out as a wine cellar and shooting range, and ultimately, it was altogether forgotten.

Decades later, in 1912, as rapid transit was connecting New Yorkers like never before, workers from Brooklyn Manhattan Transit, or the BMT (one of the three transit companies that helped create our current subway map) rediscovered Beach’s long forgotten subway station, where the old train still sat silently, waiting for its next passengers.

Theresa DeCicco-Dizon is a public historian and museum educator based in New York City.

main photo: The Pneumatic Passenger Railway, as Erected at the American Institute, Fourteenth Street, New-York, 1867. Public Domain.