Dear Lumin,

I recently reread an article written in 2023 by Ligaya Mishan titled “When Women Artists Choose Mothering Over Making Work” and have been thinking a lot lately about your decision to start having children in your early thirties, not long after grad school. Your thoughts were so crystalline, so decisive; the antithesis of the maternal ambivalence held by so many women–including myself–that has been shaped by the discourse and prejudice surrounding women artists.

Throughout her essay, Mishan speculates about the “either/or” condition of being an artist and being a mother, and the challenges women have faced both from within and from a society that doesn’t expect women to be able to do both. She cites artists who have abandoned caring for their children in order to get back to work, artists who have taken long breaks between creative production, and artists such as Tracey Emin and Marina Abramović who have vociferously and publicly rejected parenthood because of the impossibility of fully committing oneself to both. Ligaya bookends her article with anecdotes of Patti Smith and how, despite her public “disappearance” from her career and the music world in her early thirties, she ultimately “never stopped being an artist,” and “never stopped being a mother.”

You entered motherhood proudly, fearlessly, and with a plan to have children young so you would still have time to have a long and full painting career. You never hid the fact that you were pregnant, like many of us, out of fear that others would think that you were less committed to your work. You would think that more than fifty years after women’s lib and Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” women artists wouldn’t need to consider these factors. But in their 2022 report, Charlotte Burns and Julia Halperin examined the representation of women across the art market and top US institutions and reported that between 2008 and 2020 only 11% of acquisitions at US museums were of work by female-identifying artists, the representation of women artists in exhibitions at US museums was only 14.9%, and between 2008 and mid-2022 only 3.3% of global auction sales were for art made by women. These numbers tell a bleak picture about the value of women artists across our broader culture.

As you know, I’ve been thinking about the visibility and value of women artists for many years since beginning my research in 2020 on the Hudson River School and the numerous women who have been erased from its dominant narrative. Over the last few years, I’ve identified around 200 nineteenth-century women landscapists working predominantly in the northeast who were actively involved in the art world on all levels but who have been pushed to the margins of art history. What Nochlin argues and what Burns and Halperin make visible, is that this “absence” of women from the canon is not because there weren’t great women artists, but because of the “white Western male viewpoint” being “unconsciously accepted as the viewpoint” and the systemic and structural biases that continue to keep women artists from being valued, remembered, and canonized. The patriarchal perspective that has shaped art history is also deeply embedded in nineteenth-century landscape painting. Much of the discourse surrounding the Hudson River School centers on the relationship between “man” and nature, and questions of dominance, power, and control.

Even though we both thought often about landscape, albeit in very different ways, we never discussed it when we talked about our work and it’s something I deeply regret. I’ve been thinking a lot about this, particularly about the paintings you made in the last several years since the pandemic, and how they are a complete rejection of the male desire for power, domination, and control associated with nineteenth-century ideals. Your work doesn’t objectify or idealize nature, or profess to understand and know it. I look at Hot to the Touch (2023-24) every day and think about the blurred boundaries between the built and natural worlds you deftly create, how those worlds sometimes subsume each other and sometimes pull apart, endlessly tangled but providing the viewer with fleeting moments of definition. For instance, in the lower right quadrant of the painting, we see the black strokes of what I assume is a wrought iron fence weave over and under the brown, green, blue, and amber colors associated with the ground, sky, and trees, its rigid form seamlessly slipping from background to foreground and back again. In your hands, and with the quickness and assuredness of your gesture, the inorganic and organic exist without hierarchy.

The title of your last show, which was drawn from your childhood experience of “seeing” the landscape with your father without naming what you see, speaks to these qualities directly. I would love to have had an opportunity to talk to you about that title: The Unnaming. I’ve been thinking about what it means to “unname” something within the context of nineteenth-century American history and the themes of discovery, conquest, and colonization that are so closely linked to nineteenth-century landscape painting. One weapon of colonization, wielded by white men, was the renaming of places, sites, and mountains, eroding and erasing their ties to Indigenous groups and often invoking the names of white male colonizers, political figures, and the like. To not impose a name, to see without naming, or to “unname,” as you suggest, shifts the power dynamic and offers a new way of thinking about nature and the landscape that surrounds us.

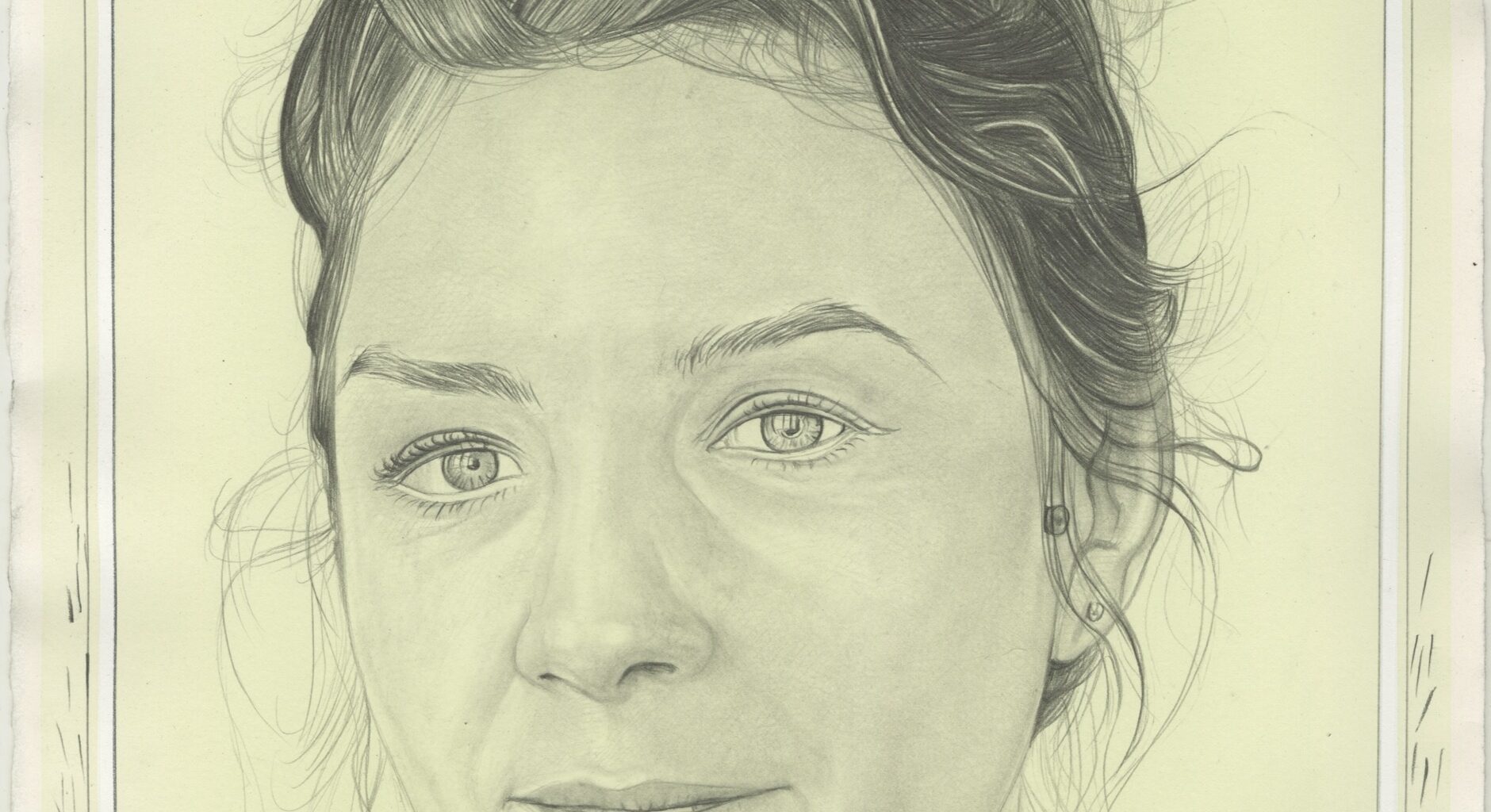

In the ARTnews article announcing your death, Alex Greenberger described your work as “part of a quest to better learn how to see the world around her.” How I wish we could talk about that world and our role in it as women artists and mothers looking at landscape from a feminist perspective. I think it’s integral to your work in many ways, not just what you made, but how you made it. When the pandemic hit and you started making work in your front garden and in the cemetery while your daughters played nearby, the usual boundaries between art and motherhood began to dissolve for you. Thinking about this returns my thoughts to the troublesome binaries that Mishan wrote about in her 2023 article. We often say “she succeeded despite being a mother.” I’m pretty sure I’ve said that before when talking about artists from the past. But I truly think in your case, Lumin, that you succeeded because you were a mother. I think of how you achieved the magical feat of being physically and psychically in two places at once, and I feel so hopeful. Thank you for being an inspiration, Lumin. I miss you so much.

Love,

Anna