Carole Caroompas

Anton Kern Gallery

September 3–October 22, 2025

New York

The image conglomerations in the paintings of the late Los Angeles artist Carole Caroompas foreshadow current mashup culture, both in terms of their play of signifiers and identities and the methods Caroompas deployed to make them. This show of nine works from 1996 through 2007 comes too late for the artist to bask in their glorious cacophony (she died in 2022), but the critical timeliness of her art ought to draw wider attention to one of LA’s most distinctive artworld personalities.

As long ago as 1980, I was enthralled by Caroompas the performance artist, whose collages and drawings were pictorial versions of the costumes, sets, and songs she performed at LA venues. In the mid-1980s, Caroompas shifted from text/image actions to painting on canvas, although for a while she continued to refer to her paintings as “set pieces.” The paintings in this exhibition show vestiges of Caroompas’s ongoing interest in performance narrative. Their story-like layers of factoids and fiction, taken and transmogrified from pop culture, mythology, and literature, are invitations to forensic pictorial reading. Caroompas was also a singer, and a variety of musical references inform the work on view at Anton Kern.

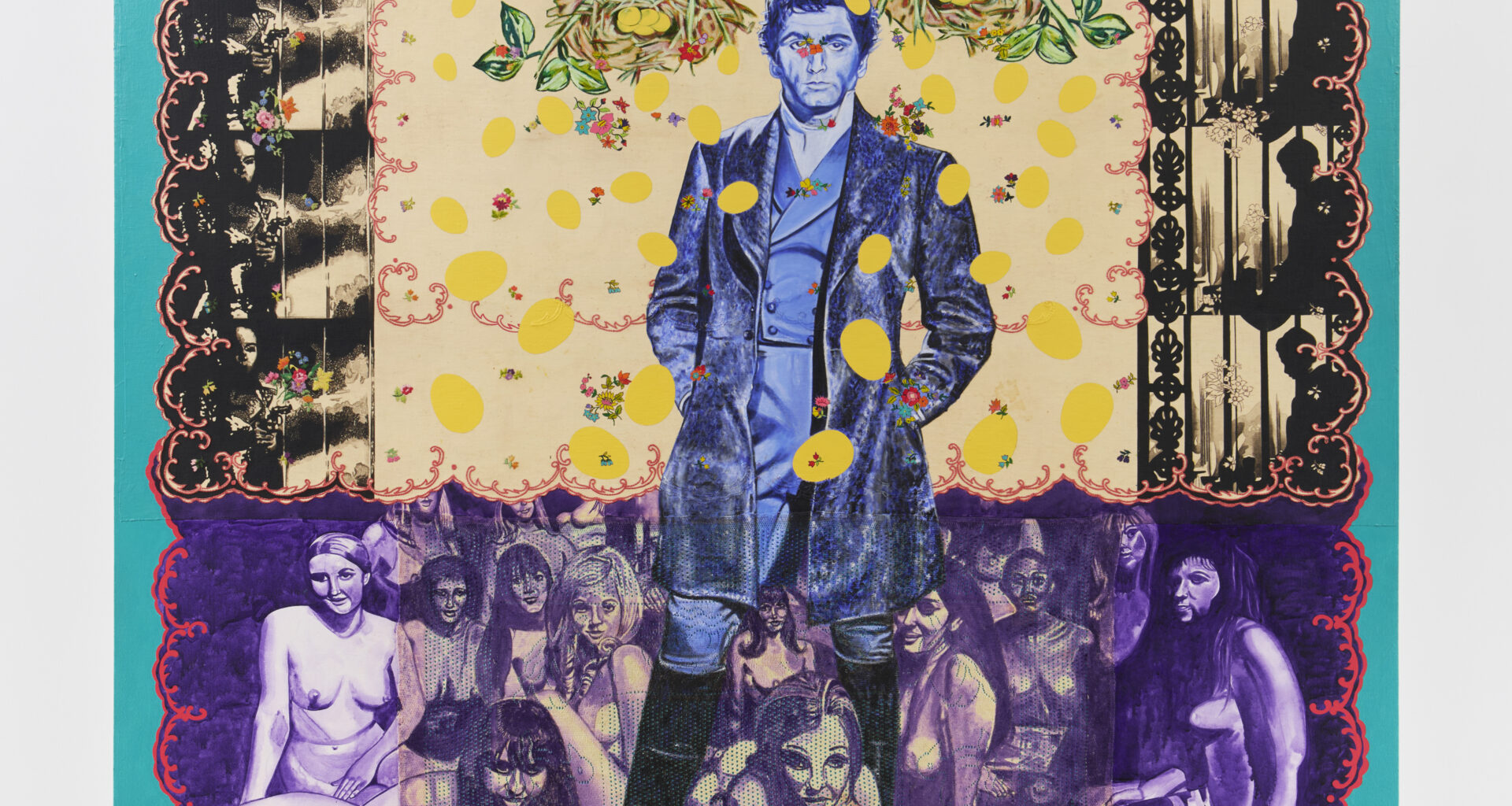

Layers of paraphrastic appropriation suffuse Heathcliff and the Femme Fatales Go On Tour: A Cuckoo’s History (1998-99), where a piece of found embroidered cloth is attached to the canvas and overpainted with illusory embroidery. On top of this stitchery, Caroompas has painted the actor Laurence Olivier in his nineteenth-century costume as the Emily Brontë protagonist Heathcliffe from William Wyler’s 1939 film adaptation of Wuthering Heights. Behind Heathcliffe’s booted posture we see clustered female nudes, including one at the lower-right corner holding a depiction of Jimi Hendrix in her lap. Indeed, Caroompas has incorporated the initial—and quickly banned—cover art from Hendrix’s 1968 record album, Electric Ladyland. The painting challenges the censorious decorum that Brontë’s critics once directed against her novel, and that the recording industry later directed against Hendrix’s cover art. Moreover, in its interplay of real and faux-stitchery, Heathcliff and the Femme Fatales Go On Tour challenges the dainty scruples manifested in embroidered furniture protective cloths.

Uncanny play on reflection occupies the center of two later paintings. In Dancing With Misfits: Eye Dazzler: Watch Out For Those Pretty Feet, Dear (2006), a collage-like grisaille juxtaposition of the legs of a dancing couple—bodies cut away so that right-side-up legs are joined to an upside-down pair of gams—is surrounded by a saturnalia of media cowboys and beauty queens (Tiny Tim and his television bride, Miss Vicki, among them). Along with the cavorting human figures are a diminutive dancing watermelon and pumpkin, while a line of shadowy dancers in black, with faux-embroidered outlines, holds the bottom of the canvas. All this cavorting should infer a joyous scene, but the attitude here is decidedly noir-ish. What’s sinister is furthered by the inverted legs in the middle, where the disambiguated woman has lost her shoes. A comparable mirroring takes place in Dancing With Misfits: Eye Dazzler: Les Deasaxes (2007), where a grisaille female figure stands hip deep in a river, dressed in a ball gown. This image is doubled and inverted such that the upside-down partner functions as a quasi-reflection. The work’s title includes a neologism, adapted from the French “les déaxés,” referring to mentally unbalanced people. The picture’s zigzagging pattern is interrupted here and there by a variety of apparitional personages, including lines of cartoon cowboys on horseback, a blood-spattered Sissy Spacek as Carrie, picket fencing and floating cross forms, and even Lawrence Welk with accordion.