Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

Zohran Mamdani campaigned on ending mayoral control of New York City’s public school system — by far his most significant education promise.

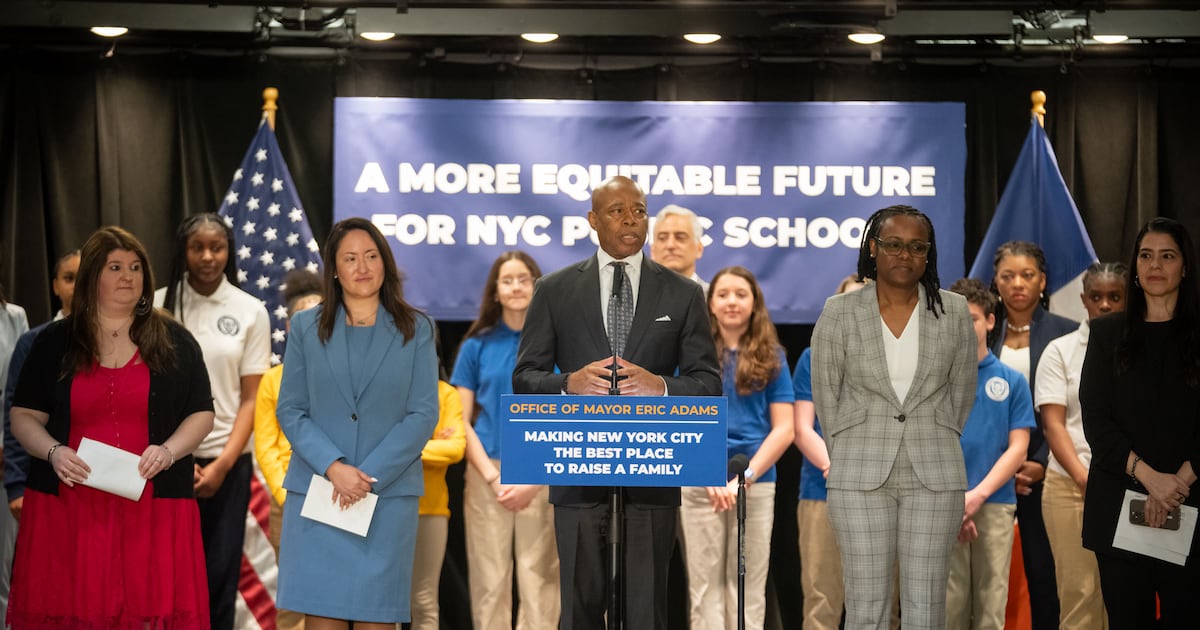

As debate intensifies over whether the mayor-elect should follow through on that pledge, a significant shift has flown under the radar: Under Mayor Eric Adams, the chief executive’s power over the school system has weakened.

On paper, the city’s mayor still exerts near-complete authority over the city’s schools. The mayor hires and fires the head of the school system and appoints a majority of the school board, known as the Panel for Educational Policy, or PEP.

But from his first months in office, Adams struggled to manage the board, which voted against several administration proposals. During his term, state lawmakers diluted the mayor’s power, adding new parent representatives to the panel while preventing the mayor from removing appointees who vote against the administration’s proposals.

More recently, as a lame duck, Adams has ceded more power. He has allowed three of his 13 mayoral seats on the 24-member board to go unfilled, handing the majority to board members selected by others.

And in recent months, the panel has repeatedly voted against City Hall’s proposals — an extraordinary departure from boards under previous administrations that only occasionally bucked the mayor. On Wednesday, in an unusual move, they voted down the Education Department’s budget.

“The idea that we are rubber stamps and aren’t making judgements — that’s in the past,” Greg Faulker, the chair of the board who was appointed by Adams, said of the board’s larger role.

Six months after Mamdani takes office, it will be up to lawmakers in Albany whether to extend mayoral control in its current form. The question for Mamdani is whether he will lobby lawmakers for sweeping reforms or embrace a PEP that has become detached from City Hall.

PEP seen as ‘mere formality’ under some mayors

During the campaign, Mamdani pledged to end mayoral control and replace it with a system that shares power with families and educators, though he has not said what that means.

His critique of mayoral control has zeroed in on the PEP, which he contends does not take community input into account, especially on contentious school closure, mergers, or re-location proposals.

“They go to a hearing about the future of a school that their children go to — eight hours of testimony,” Mamdani said in a recent television interview. “Meanwhile, the decision was actually made weeks and months prior, and this is just a mere formality.”

Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg won mayoral control of the school system in 2002. He did not tolerate dissent from the PEP — and famously fired two of his own appointees for opposing a plan to end “social promotion” of students from one grade level to the next. After replacing them in what was dubbed the “Monday night massacre,” the proposal passed.

Ultimately, Bloomberg’s board passed numerous controversial proposals, including dozens of school closures despite community resistance.

Former Mayor Bill de Blasio, who ran in opposition to many of Bloomberg’s education policies, vowed to give the board’s mayoral appointees more independence. But little changed in practice. The board typically voted in lockstep with the administration’s wishes, with only a few exceptions. In one episode, a mayoral appointee cast a decisive vote against two school closures proposed by the administration. In short order, she was off the board.

Adams loses his grip on mayoral control

From his first months in office, Adams lost the tight grip on the PEP that other mayors have enjoyed.

Adams was slow to appoint panel members early in his term and was forced to hastily withdraw one of them after her anti-gay writing came to light. With a vacant slot, City Hall lost a routine vote to approve the city’s funding formula. (It was approved at the next month’s meeting after the chancellor vowed to review the funding scheme.)

But managing the board has also grown more complex. The PEP has nearly doubled in size since 2019 — a response from state lawmakers to concerns that the governance system is not responsive to community input.

It now includes 24 voting members, including five selected by parent leaders, one chosen by each of the five borough presidents, 13 mayoral appointees, and a chair selected by the mayor from a list devised by state lawmakers. (The schools chancellor, a secretary, two students, and a representative from the comptroller’s office serve as non-voting members.)

The city’s Panel for Educational Policy has voted down some Adams administration proposals at recent meetings. (Alex Zimmerman / Chalkbeat)

The city’s Panel for Educational Policy has voted down some Adams administration proposals at recent meetings. (Alex Zimmerman / Chalkbeat)

Members serve one-year terms, and the mayoral appointees can’t be removed if they vote against the administration’s wishes, a change state lawmakers made just months after Adams took office.

“Having PEP members who can’t be summarily dismissed as Bloomberg did is an important structural difference,” said Jeffrey Henig, a political science professor at Columbia University. “It can be a more vital body that sometimes stands up to the mayor.”

The larger board means more panel members are weighing in on any given decision, making it harder to forge a majority if there are more dissenting voices. City Hall must also devote more effort to recruiting panel members to fill the mayor’s 13-member majority.

Asked why the mayor has not filled three vacancies on the board, a City Hall spokesperson said it can be difficult to quickly find qualified people. The position is unpaid and requires attending monthly public meetings that sometimes stretch past midnight.

“Our administration continues to work hard to ensure this panel is well-staffed,” City Hall spokesperson Zachary Nosanchuk wrote in an email.

Notably, Mamdani may not be able to appoint a majority to the PEP when he takes office because the current members’ terms won’t expire until June.

‘You need to listen to us’: A more independent PEP opposes the administration

No issue has reflected the changing power dynamics between the mayor and the PEP more than the recent negotiations over school bus contracts, which cost nearly $2 billion each year.

After the contracts expired over the summer, city officials agreed to a five-year extension with the bus companies. But dozens of parents and advocates flooded PEP meetings to argue that they should approve a shorter extension to give officials more room to overhaul the troubled system entirely.

“Don’t reward bad behavior,” parent Christi Angel said at the September PEP meeting. “This is a broken system.”

Despite the companies’ handshake agreement with the city for a five-year contract, the PEP passed a resolution saying they wouldn’t support it — including the mayoral appointees. The bus companies later threatened to lay off their workers, potentially grinding the whole system to a stop. The PEP held firm.

“Once that resolution passed, it was game over,” Faulkner said, noting the administration encouraged the PEP to approve a five-year deal. “And the fact that it passed unanimously was a further indication that you need to listen to us.”

On Wednesday evening, the PEP approved a three-year extension of the contracts.

Shortly after, the chancellor, who is in the running to keep her job under Mamdani, signaled her support of a more independent PEP.

“With an incoming administration that has really spoken about its values around community engagement, it’s a great time to reset,” Aviles-Ramos said.

Her comments came at a remarkable moment. Minutes earlier, the board voted down the Education Department’s budget after concerns surfaced about growing administrative spending, including on the chancellor’s office. (The budget could be approved at a future meeting.)

Growing PEP independence stirs debate

The panel’s newfound power has earned varied reactions.

Last month, the board voted down more than $4 million in technology contracts after families and educators raised concerns at a PEP meeting about the companies’ use of artificial intelligence.

One of them was a deal with an AI company launched by former football star Colin Kaepernick, who appeared at a conference alongside Aviles-Ramos a week before the vote. It was an embarrassing setback for the chancellor, who has recently touted efforts to bring AI into schools.

“I was really surprised and thrilled,” said Leonie Haimson, a student privacy advocate who criticized the AI contracts before the vote at last month’s panel meeting. Still, Haimson believes the PEP should have even more independence from the mayor, noting that the board has still approved proposals under Adams despite intense community pushback.

“A lot of important decisions are made without the transparency and accountability that should be required,” she added.

Others have been frustrated that the mayor has lost power over the PEP, arguing the increasingly sprawling board doesn’t always have expertise in what they’re voting on. One technology contract they voted down was a $1.5 million deal with Kiddom, a digital platform that helps teachers access curriculum materials.

Abbas Manjee, Kiddom’s cofounder and chief academic officer, said the company’s use of artificial intelligence is teacher-facing and felt the PEP members didn’t seem familiar with the platform before lumping it in with other AI companies.

He noted the company helps schools access reading and math materials that are at the center of Adams’ curriculum mandates, a top mayoral education priority.

“It’s almost like you’re shooting yourself in the foot,” Manjee said. “Where is mayoral control?”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.