As evidenced by the sideline brawls and sign-stealing scandals of games past, emotions run high on college football gamedays. Sometimes so high that even the teams’ mascots feel compelled to get in on the action.

At least that’s what happened at the 2019 Sugar Bowl between the University of Texas and the University of Georgia. The two schools’ mascots, Texas’ longhorn “Bevo” and Georgia’s bulldog “Uga,” were getting together for a pregame photo-op when Bevo (who weighs roughly a ton) jumped out of his enclosure and charged at Uga.

Neither mascot nor any people were injured, though the narrowly avoided disaster rattled the handlers, photographers and commentators watching live.

Pals #HornsInNOLA #SugarBowl pic.twitter.com/K7YJ7djv4F

— BEVO XV (@TexasMascot) December 31, 2018

Beyond being an instant viral video, the moment brought new attention to the question of risk versus reward when using large, wild animals as sideline mascots. Almost six years later, the teams have had several matchups — though Bevo and Uga have stayed far away from each other.

In that time, tensions have grown off the field between animal rights groups calling for colleges to retire their live mascots, and football programs who are incredibly loyal to the tradition of using them.

Catie Cryar – a Texas alum and the senior manager of media relations at PETA – has grappled with her relationship to the issue as both a Texas football fan and animal activist.

“I love my school and I have so much pride in being a Longhorn,” Cryar said. “It always made me sad to see Bevo paraded around in front of a noisy crowd, and I wasn’t the only one.”

Cryar compared Texas’ treatment of Bevo to “shuffling him around like a piece of equipment.”

PETA is one of many animal rights groups that have spoken out against the use of live wild animal mascots for years, citing incidents like Bevo and Uga’s altercation to pressure universities to stop the practice.

When asked how Bevo is doing today despite his past controversies (which include a ban from the 2024 Peach Bowl due to concerns over adequate space for him), Mike Rosen, who is Texas’ assistant vice president for media relations, responded, “Longhorns are naturally calm, friendly and social animals, uniquely suitable for human interaction.” Rosen added that only “those with the most docile demeanor represent the University as Bevo.”

The University of Texas does have a costumed mascot named “Hook ‘Em,” who attends most games alongside Bevo and keeps fans energized even when space or travel restrictions permit the longhorn from attending.

According to Rosen, Bevo “roams free on a 300-acre ranch, has a personal veterinarian, is nurtured in his travels, has never been sedated and regularly interacts with adults and children to bring great joy to our Texas fanbase.”

Ken Murray / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

Ken Murray / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

“Bevo” the Texas Longhorn mascot is brought under control after jumping his pen in an attempt to attack the Georgia Bulldog mascot before the Sugar Bowl football game between the Texas Longhorns and Georgia Bulldogs.

Bevo is one of the estimated two-dozen live animal mascots still in use today at accredited colleges and universities. That number has shrunk in the last few decades as universities have made the switch to costumed mascots.

The most recent switch happened in 2020 at the University of Memphis. When their tiger Tom III passed away, the university opted to sponsor a tiger at the Memphis Zoo instead.

What is the origin of live animals as mascots?

While some might associate live mascots with the SEC, the first known live animal mascot came from Yale University in the 1890s, when a student bought a bulldog and deemed him “Handsome Dan,” the school’s new mascot.

The trend caught on at more universities, with virtually no regulations to meet until the Animal Welfare Act was passed in 1966. Even today, laws around owning animals still vary significantly by state, hence animal rights groups’ struggle to make any major strides in their effort to end live mascot use.

Devan Schowe, who is a member of the animal rights group Born Free USA and wrote an op-ed about live mascots earlier this year, attributes the fanfare of live animal mascots to fan desensitization.

“I think that a lot of people have become really desensitized to seeing wild animals in captivity in a harmful setting, but not having alarm bells going off because it’s become so normalized,” Schowe said.

“No one is going to skip a game because you have a costumed mascot instead of a live animal,” said Ashley Byrne, PETA’s director of outreach. “I’m simply not going to have that. That’s not why people are there.”

Byrne referenced universities like Cornell, Brown and UCLA – who all had live bears as mascots before switching to costumed ones – as examples that live animals don’t necessarily mean higher morale in the stadium.

While many schools are either standing firmly by their live mascots or abandoning the practice completely, others are trying to find a middle ground. One university that aims to do so is Baylor University in Texas, whose two bear mascots do not attend football games and instead live permanently in a habitat on campus.

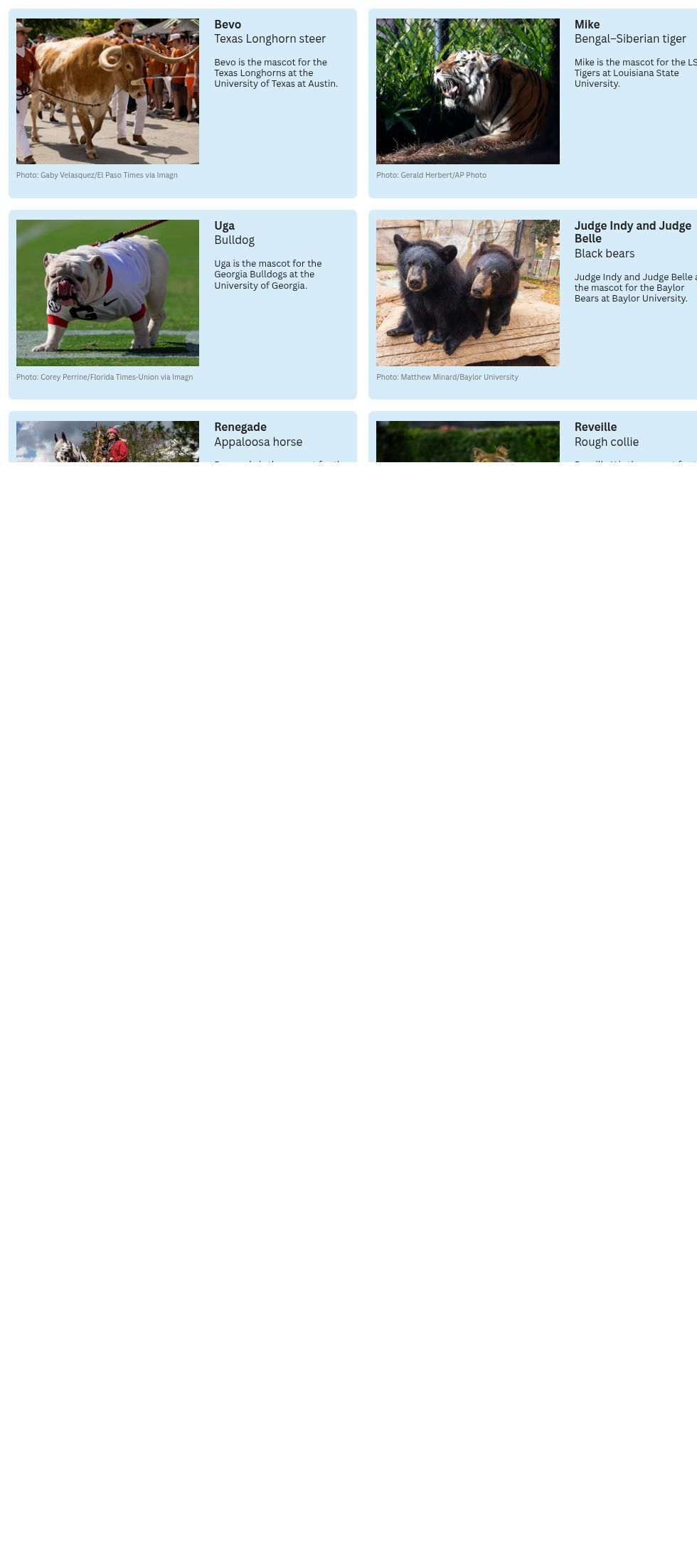

“Baylor University has a deep commitment to treating all living things in God’s created world with compassion,” said Lori W. Fogleman, assistant vice president of media and public relations for Baylor. The school’s current bears are 2-year-old Indy and Belle, who have been with Baylor since 2023 when they came from an oversized litter at a wildlife park in Idaho.

Matthew Minard / Baylor University

Matthew Minard / Baylor University

Live mascots Judge Indy and Judge Belle at the Baylor Bear Habitat in 2023.

Baylor’s black bears attended football games from their introduction in 1917 until the early 2000s, when the university made the move to keep them in an on-campus habitat to mitigate the environmental stressors associated with Saturday gamedays.

According to Baylor’s Bill and Eva Williams Bear Habitat’s website, the habitat primarily focuses on conservation and education, and receives regulatory oversight and licensing from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Matthew Minard / Baylor University

Matthew Minard / Baylor University

Educational signage at the Bill and Eva Williams Bear Habitat in 2024.

“The Bear Habitat caregiver team ensures the bears receive a healthy diet and are well cared for 365 days a year, regardless of inclement weather, university breaks or holidays,” Fogleman shared.

While Baylor’s approach to live animal mascots seems like an obvious compromise for other universities to follow, it’s not as easily replicated without strong financial commitments from the university or private donors that would ease the need for public appearance fees. However, it does give a look at one way to make the tradition of keeping live mascots more ethical without deserting it completely.

There is one tradition that Baylor seems to be content with leaving in the past, though.

“The bears also do not drink Dr Pepper, a practice that stopped almost 30 years ago in 1996,” Fogleman said.