Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in the May/June 2002 issue of the Adirondack Explorer, four years after the state purchased approximately 15,000 acres of land from Marylou Whitney and John Hendrickson for the William C. Whitney Wilderness Area. We are republishing the story in response to reader comments suggesting state land ownership reduces local tax revenue. This analysis by Phil Brown found that towns often receive more tax revenue from state-owned land.

By Phil Brown

When the state purchased Little Tupper Lake in 1998, Long Lake Supervisor Thomas Bissell opposed the deal, arguing that it would hurt the local economy. Whether it did or not is debatable, but one thing’s for certain: It helped the local tax base.

Before the sale, owner Marylou Whitney paid $90,835 in annual taxes on the 15,000-acre property. This year, the state paid $245,059 on the same lands, a 170% increase. Even though the windfall was not big enough to reduce the tax bills of town residents, Bissell said, “the extra money was welcome.” In fact, Bissell said he would not mind much if the state bought the remaining 35,000 acres owned by Whitney in the town of Long Lake.

“It’s only a matter of time before the state gets the rest of the property,” said Bissell, who lost re-election last fall. “I’m not passionate one way or the other about it. But I don’t want to see it classified as Wilderness [where motorized recreation would be banned].”

That Bissell is not flat-out opposed to further state acquisition may not qualify him for the Adirondack Council’s Conservationist of the Year Award, but it does represent a step back from the hard-line position, popular among the region’s politicians, that localities always suffer when the state buys land for the “forever wild” Forest Preserve. In fact, towns and school districts usually come out ahead in tax revenue—a point often lost in the preservation-vs.-development debate.

Gov. George Pataki’s goal to preserve 1 million acres throughout the state in the next decade ensures that the debate is not about to go away. If that goal is to be met, the state will have to save a good deal more land in the Adirondacks (where most of the remaining open space exists), either through conservation easements or outright purchases. Although it’s uncertain what properties the state may be looking at, the Explorer reviewed the tax data for five large tracts coveted by Adirondack preservationists and found, in every case, that localities stand to gain if the land is added to the Forest Preserve or protected by easements. Together, they could reap hundreds of thousands of dollars in extra revenue.

How state land generates more tax revenue

Why is this? The state Forest Preserve, unlike private timberland, is not eligible for tax exemptions. As a consequence, it’s not uncommon for the state to pay four or five times as much per acre as timber companies do. With 2.6 million acres, the state is by far the largest taxpayer in the 6 million-acre Adirondack Park. It doled out roughly $48 million in town, county and school taxes on Adirondack lands in the last fiscal year.

In the examples that follow, the Explorer compared the taxes paid by the private landowners with the amounts that would have been paid if not for exemptions. The latter figures give a rough idea of what the state would pay if it bought the land or acquired easements. (The correspondence is not exact, because the state would not pay taxes on buildings that may be on the properties.)

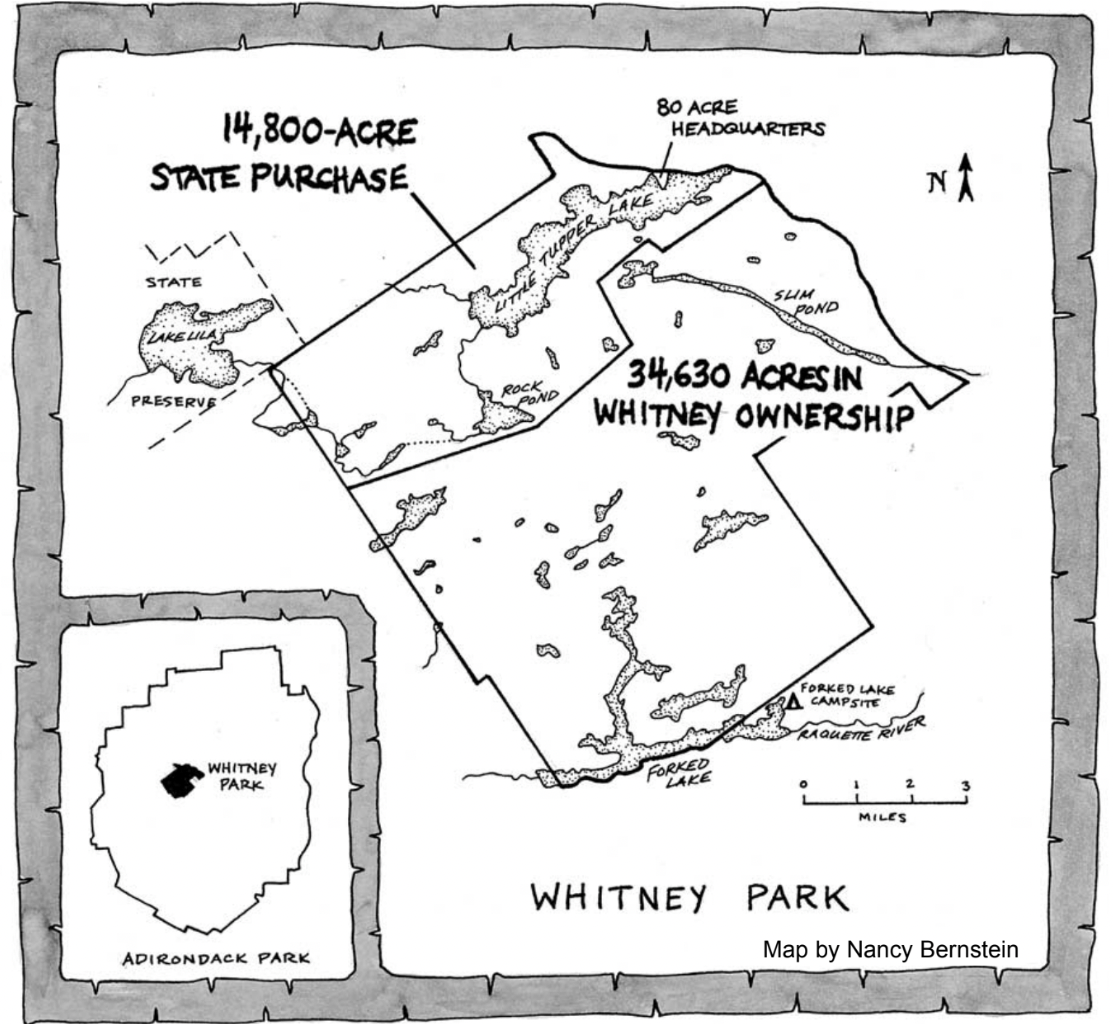

WHITNEY PARK. Marylou Whitney still owns 34,630 acres south and east of Little Tupper Lake. With its numerous ponds and streams, the tract is a paddler’s paradise. Whitney paid $211,320 in taxes on the property this year, according to Long Lake assessor Bruce Jennings. If the state owned the land, it would have had to pay $339,585—a 61% increase. Whitney’s husband insists said the property is not for sale.

FOLLENSBY POND. This 14,000-acre tract includes a large wilderness lake that drains into the Raquette River between Axton Landing and Tupper Lake. It also includes 10 miles of shoreline along the river. Most of the property lies in Harrietstown, where the owner paid $46,090 in taxes this year, according to town assessor Sandra Aery. The state would have paid about $148,720 on the same parcels—a 323% increase.

TAHAWUS TRACT. Known as the southern gateway to the High Peaks, this 11,200-acre property contains Preston Ponds, Henderson Lake (the source of the Hudson River) and the 3,540-foot Mount Adams. Nearly all of it lies in the town of Newcomb, where the owner, NL Industries, paid $150,830 in taxes, according to Essex County records. Without exemptions, NL would have paid $168,000—an 11% increase.

FORMER IP LANDS. Last year, the Adirondack Nature Conservancy bought 26,500 acres of International Paper land that includes several canoe waterways: Round Lake, Round Lake Outlet, Bog Lake, Clear Pond and Shingle Shanty Brook. The conservancy intends to sell some of the land to the state. The entire property now generates $122,720 in taxes, according to Jennings. The tax bill without exemptions would have been about $136,800—an 11% increase.

DOMTAR INDUSTRIES. The Canadian timber company has been trying for years to sell the state conservation easements on 105,000 acres in the northeastern Adirondacks. Under easements, the state would own recreational and development rights to the land and pay most of the taxes, but the company could continue logging. Data for all of Domtar’s land were unavailable, but the company paid $149,900 in taxes on its 31,400 acres in Clinton County. In a typical easement, the state might pick up 75% of the tax bill, and this portion would be ineligible for exemptions. Using this figure, the state would have paid $173,040 on the same parcels—a 15% increase, without even buying the land. Presumably, localities would see similar tax benefits on the other 73,600 acres.

In each case, some or all of the property receives exemptions under 480 or 480a of the Real Property Tax Law. Under 480, timber is not assessed for tax purposes, which greatly reduces the overall tax burden, and the assessment is frozen until there is a townwide revaluation of property. Although this program was closed to new applicants in 1974, it remains in effect for lands enrolled before the cutoff date. Under 480a, which replaced the earlier program, owners who adhere to a 10-year forest-management plan may qualify for an 80% exemption. The exemptions can vary from owner to owner, depending on a number of variables, such as the amount of waterfront and the percentage of land enrolled in the program.

The tax breaks are granted only for land kept in timber production. Since timberland can sit for decades without being logged, owners might otherwise be tempted to sell their idle land to pay taxes. Preservationists support the exemptions as a way of discouraging fragmentation and development in the backcountry.

Although exact figures are unavailable, the amount of Adirondack land enrolled in the forestry programs is substantial. In Hamilton County, which includes Whitney Park and extensive IP holdings, more than a third of the private land qualifies for exemptions. Although these lands account for just 3% of the county’s total assessment, most are concentrated in two towns, Long Lake and Morehouse. On average, these timberland owners receive a 43% tax break. The difference in taxation can be striking. The state, which owns nearly 70% of the land in the county, pays an average of $14.34 per acre in taxes. Whitney pays $6.10 per acre. International Paper paid $4.25 per acre on the land sold to the Nature Conservancy (which also qualifies for exemptions).

The disparity is due not only to the forestry programs. Forest Preserve lands are usually assessed higher than private timberlands: Because the state land is not logged, it often contains more timber, or it will as the trees mature. The difference in timber value can easily translate into a doubling of the taxes on a piece of property. Assessments of state land reflect the timber’s value even though, by law, trees cannot be harvested in the Forest Preserve.

More important, the state also pays “transition assessments” in the Adirondacks on top of its regular taxes. These are intended to keep the state’s share of the tax base at a more or less constant level. Let’s say, for example, that state land once accounted for 30% of a town’s assessed value. If a revaluation reveals that the state land now accounts for only 25% of the assessed value, owing to the rise in value of other property, the state will make up all of the difference in the first year. That is, it will pay taxes as if its land were still worth 30% of the town’s assessed value. Thereafter, it will pay smaller transition assessments for a number of years. If the town does another revaluation down the road, the process will start anew.

In Essex and Hamilton counties, the only two counties lying entirely within the Park, the state paid roughly $9.1 million in transition assessments last year, according to figures provided by the state Office of Real Property Service (ORPS). These payments accounted for 38% of the state’s tax bill in the two counties.

Perhaps no community is reaping the benefits of transition assessments more than the town of Newcomb (population 481) in the central Adirondacks. Last year, the state paid about $809,000 in regular taxes and $3.1 million in transition assessments, according to ORPS. On average, the state paid $63 an acre. In contrast, Finch, Pruyn & Co., which owns 53,000 acres of timberland in the town, paid less than $4 an acre. Nevertheless, the company is suing to lower its taxes, which prompted Newcomb Assessor Lowell Stringer to suggest recently that the town would be better off if the state bought Finch, Pruyn’s land.

Local officials remain skeptical

Despite the apparent benefits, most Adirondack politicians remain leery of or hostile toward state acquisition, which they say stifles economic growth. Newcomb Supervisor George Canon, for example, does not want to see the state buy either the Tahawus Tract or the Finch-Pruyn lands. He notes that logging jobs would be lost if the lands were added to the Forest Preserve. He also yearns for the day when the NL iron-ore mine is opened again—an option that would be precluded if the state owned the property.

Canon said the town would not necessarily see a spike in tax revenue if the state bought the Tahawus Tract, because a $1 million lodge on the property might then be torn down. In any event, he argues that the state should be required to pay localities to make up the tax breaks given timberland owners. The state legislature was poised to pass a bill for that purpose last year, he said, but it got shelved in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks.

“It’s off the table until the governor feels he can afford it, but we’re going to keep pushing,” said Canon, who is also president of the Adirondack Association of Towns and Villages. Environmental groups also support the bill, which has been kicking around for years, even though it would moot one of the economic arguments for state-land acquisition.

Long Lake Supervisor Christine Snide said she would rather see Whitney Park developed than sold to the state. “I get very nervous when the state’s share of property keeps increasing,” she said. “Slowly, we’re being squeezed out of here, and I don’t like that feeling.”

In Harrietstown, Supervisor Larry Miller said he didn’t know, without studying the matter, whether he would favor the state’s acquiring Follensby Pond, but he generally is opposed to expanding the Forest Preserve. The state already owns three-fourths of the land in the town, and Miller said there is little room left for growth.

Likewise, town supervisors in the northeast Adirondacks expressed reservations about a Domtar deal. “We’re concerned about the state buying up land,” said Mary Ellen Keith of Franklin. She added, however, that she is unsure whether the deal would be good or bad for her town.

Economic study finds nuanced picture

Adirondack officials often claim that when the state purchases land or development rights, the local economy is hurt in two ways: forestry jobs are lost and more land is closed to development. Preservationists counter that the economic future of the Park lies in tourism, not forestry or backcountry development. A 2000 study by three economists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute suggests that the truth lies somewhere in between.

Jon Erickson, one of the study’s authors, notes that the forest-products industry in the North Country has been struggling in an increasingly global marketplace, with paper-mill closures and layoffs and large tracts of land changing hands. The study attempts to answer the question: When timber companies sell their holdings, what can be done to fill the hole in the Park’s economy?

The study estimates that 200,000 acres of active timberland contributes just over $100 million in income to the Adirondack economy. If this amount of land were taken out of timber and paper production, the study says, developers could not build enough houses under current zoning regulations to make up for the long-term economic loss. Likewise, if the state purchased the land, the number of additional tourists required to break even might be unattainable, especially in remote parts of the Park.

Nevertheless, if the choice is between development and state acquisition, Erickson said, localities would be better off in the long run if the land were added to the Forest Preserve at full taxable value and managed for tourism. One reason for this, he said, is that state land does not encumber communities with the costs of services, such as water, roads and schooling, that accompany new homes and population growth.

An even better outcome, from an economic standpoint, occurs when the state strikes a deal that divides the land between easements and acquisitions, Erickson said. In the Champion International deal a few years ago, for example, the state purchased only the choice recreational lands, such as river corridors, ponds and a summit, and acquired easements on the remaining land to allow logging to continue. Thus, localities can enjoy the benefits of both tourist expenditures and forestry. In addition, the timber companies benefit by shifting most of their tax burden to the state, which helps them stay in business. Finally, the communities will see a jump in their overall tax revenue if the lands had been enrolled in the 480 or 480a programs prior to state acquisition.

For all these reasons, Erickson believes that the Domtar deal would be “a good thing” for the economy of the northeastern Adirondacks, a corner of the Park where public land is scarce. He cautioned, however, that communities will not reap the full benefits unless the state makes the land accessible by building trails, parking lots, canoe launches and other facilities. He said he could not comment on the merits of the other potential deals without knowing more details.

Canon remains unconvinced that public ownership is better than development. He said Newcomb sees few tourist dollars from hikers and others who use the neighboring High Peaks Wilderness. Yet, he said the construction of 250 homes on Goodnow Flow added $20 million to the assessment rolls “at little or no cost to the town.”

“I don’t buy his conclusions,” Canon said.

Some observers doubt that Adirondackers would ever concede that state land can be beneficial, even if it were demonstrated by a Euclidean proof. “They’ve been told so much that it will hurt them that they have come to believe it,” said George Davis, who served as executive director of Gov. Mario Cuomo’s Commission on the Adirondacks in the 21st Century, which called for more public acquisition of land. “They just don’t like the state. They don’t like big government. It’s us against them.”