Free Upper West Side News, Delivered To Your Inbox

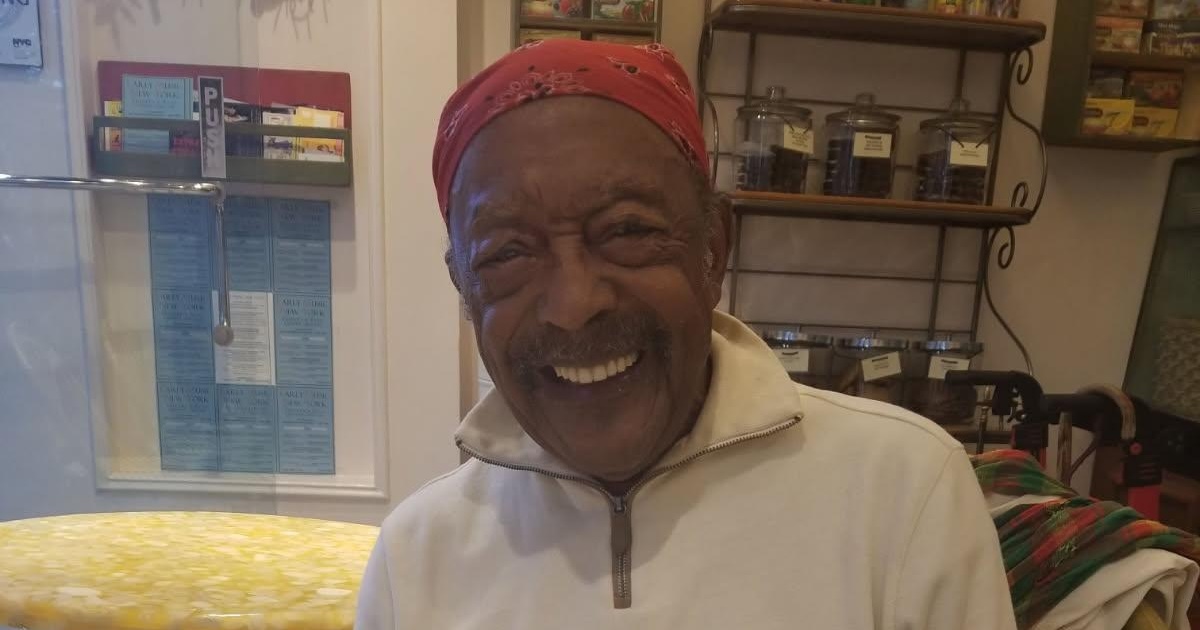

Flowers and a memorial note sat on Theo’s bench at Muffins Café on Friday, November 21. Theodore Dixon, 100, had passed away the day before. The World War II Navy veteran, who attended the distinguished Bruton Heights School in Williamsburg, Virginia, had been briefly hospitalized and was recovering at The Riverside on the Upper West Side before peacefully drifting away in his sleep that morning, without pain. A group text was started by those who loved him to honor a man who was a beloved neighborhood fixture, known for his beautiful spirit, kindness to children and dogs, and wisdom.

“This is the time I would normally call him every day,” said Lezlee Bellanich, trying to hold back tears during a call with ILTUWS at 9 a.m. on Saturday, November 22. Despite moving to St. Augustine, Florida, Bellanich and Dixon never lost touch. When her mother, who was also close with Dixon, passed away from blood cancer, she told Theo to look out for her daughter. “And he took that very seriously. And he kind of became like my dad, you know, my father.” Describing the life event as a “transfer of energy,” the calls with Bellanich and Dixon started weekly, then three times a week, then daily, she remembered. Dixon wanted to know all about her kids, River and Sky, who grew up connecting, like many others, with Theo on the bench at Muffins Café. Theo would also ask about Bellanich’s husband, Captain Rob, and what was happening with their dinner charter yacht in Jacksonville. Being a Navy man, Dixon knew all too well the challenges of maintaining a vessel in salt water.

Before Theo became famous on the Upper West Side, he aspired to train as a Navy pilot but was told that was not an option. He would soon find himself fighting a war on two fronts starting in 1942: “not only combating the enemies in the South Pacific Theater — the Imperial Japanese army — but also encountering extreme racism for the first time in his life within the ranks of the U.S. military,” wrote Susan Wands, a supporter of the 71st Street Block Association who wrote a short biography of Dixon. “After basic training was completed in Chicago, Theo was stationed in San Francisco, where he was shipped out to Pearl Harbor on the ship Japara, to defend the islands in the South Pacific.”

En route to Honolulu, Theo and other Black Navy men discovered their barracks were segregated and they were not allowed to go through the white living quarters to eat in the dining hall. There was an uprising and lives were lost, leading to the ship’s population being confined until the military could sort out what happened. The soldiers were then put on another ship back to San Francisco, which had separate dining and sleeping quarters for the Black soldiers.

Cue Tokyo Rose, the name Allied troops in the South Pacific gave to a group of female English-speaking radio broadcasters who spread Japanese propaganda aimed at demoralizing Allied forces during the war. “He would talk about Tokyo Rose,” said Bellanich. “She was a propagandist. She spoke English, and she was trying to get a lot of the Black soldiers to defect. She would say, ‘Why are you fighting for a country that doesn’t even give you rights?’” While some Black soldiers abandoned their posts, Dixon did not, despite being treated poorly. “He was loyal to our country.”

While enlisted, Theo spent thirty days in a submerged submarine, but the experience confirmed his desire to fight above water. “In 1943, Theo was stationed on Saipan, the largest of the Northern Mariana Islands, the scene of terrible military battles,” wrote Wands. “The capture of Saipan pierced the Japanese inner defense and left Japan vulnerable to strategic bombing.” This lost foothold pushed the Japanese government to inform its citizens that the war was not going according to plan — Japan was in trouble. “The battle claimed more than 46,000 military casualties and at least 8,000 civilian deaths.”

Dixon’s duties included upkeep of the Enola Gay, which dropped the atomic bomb “Little Boy” on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Once the bomb was dropped, Theo was assigned to the radioactive battlegrounds before carrying heavy photography equipment for the Pathe film company so they could record a newsreel, face-to-face in the nuclear aftermath, to document the cataclysmic destruction. “Theo wore a mask and some heavy clothes, but there was little done for protection to keep the exposure down from the high levels of radioactivity for the film crew and the soldiers,” wrote Wands.

One horrific sight after another, as the Japanese government emphasized death over dishonor, and official wartime directives prohibited surrender. “You shall not undergo the shame of being taken alive,” was one such order. Dixon laid eyes on Japanese soldiers taking their lives by the ritual of seppuku, also known as hara-kiri. “You literally take a knife and you go through your body and your intestines,” Bellanich told ILTUWS. “Yeah, these are the things he saw. And he saw things that are unspeakable; a lot of the people would take the metal (off the soldiers) and things like teeth, you know, that they needed to survive.”

Serving his country heroically, the war ended on December 29, 1945. Theo came back to New York City with an honorable discharge and quickly established himself as a fixture on Sugar Hill, in the heart of Harlem. He had aspirations of becoming a lawyer but was discouraged because of his race, being told he would struggle to succeed in the field, perhaps only handling low-level cases. He attended City College and several other schools, earning degrees in early childhood education, psychology, and sociology. Dixon worked for the New York City Environmental Protection Agency during the Lindsay administration and later sold commodities. After living on 57th Street in Manhattan, he moved to 71st Street, where he became a cherished resident and honorary “Mayor of the Block.”

Theodore Dixon, 98, inducted into New York State Senate Veterans Hall of Fame

Dixon is now a legend, known to greet children and dogs on the street when they passed by Muffins Café. “He spent many, many years coming pretty much every day, in the morning when kids were going to school, and in the afternoon, when they were coming back,” said Biba Naouai, owner of Muffins with her husband Ali. “He would greet the kids he knew, all of them as they were growing up. And he would also like to hold on to the dogs as the owners went into our café to get their stuff. Anyone who sat next to him, you know, he would be drawn into a conversation about keeping love alive, and he would share his philosophy.” Naouai said she’s part of the group that became Theo’s adopted family when he started using a wheelchair and needed more help from personal care assistants. “But he would still come when he could, and sit either right next to the Muffins shop or on the corner and greet the kids who were increasingly kids who, you know, didn’t know him, because his visits became less frequent. But there are kids who have grown up knowing who he is.”

Those who knew Dixon best understood that he prided himself on being a veteran and someone who never shied away from adversity in any form. He also loved the ladies.

“Despite the message of love that he was spreading, he was kind of a tough guy, you know. He called himself a gangster and hinted at some shady activity in his past,” said the Muffins Café owner. The movie American Gangster, starring Denzel Washington, touches on elements of the era when Dixon was a member of the Sugar Hill Gang (not the rap group), during which he supplied narcotics to people like “Ray Charles and some of the brilliant jazz musicians who did get hooked on drugs or used them for creative purposes — but he wanted to make sure that they were safe, you know, that they weren’t going to overdose,” said Bellanich, who added that she recorded countless hours of her conversations with Dixon over the years. Upper West Sider Ruth Nerken also made a seven-minute documentary about Dixon that she plans to enter at film festivals.

Dixon served time in Attica prison after apparently upsetting the judge during his trial, we’re told. “He was treated better in Attica as a prisoner than he was in World War II. He talked about Attica fondly, which shocked me,” Bellanich said, noting that Theo definitely dealt with post-traumatic stress disorder after the war. “Theo’s life experience — Theo deserves a book written about him. And if it’s not me, I have to be part of the source, because I lived his stories. I can see them all. I can see Penniman Road. I can see Williamsburg. I can see him.”

Dixon’s parents, Eliza and “Black George” Dixon, and his younger sister Ruth grew up on a farm in Virginia with pigs, chickens, and a big red rooster, where fresh food was plentiful. They valued a good education.

Theo’s family in Virginia

When Dixon was with us on the Upper West Side, he brought his best self, carrying all the wisdom he had learned along the way, preaching love and what many would now famously call his “Theo-Isms”:

– “I’m here for a reason, not just a season.”

– “We’re just passing through on borrowed time.”

– “Children have pristine minds.”

– “Life is a cabaret, you’re supposed to enjoy it.”

– “A good name is worth silver and gold.”

– “I’m here to keep love alive.”

– “Keep your mind happy, and think positive.”

“Theo has to be celebrated,” said Jane Meehan, who lived in the same building as Theo, The Hargrave House on West 71st Street, where she helped take care of him in his later years but knew him for decades. She also praised Theo for his excellent style and attire. On Friday, November 21, while flowers and a memorial note were left on Theo’s bench, ILTUWS went to Muffins Café and spoke with employees and customers, who were all together mourning and honoring the passing of a great man. “We both shared a ferocious pride that we were both Leos,” said Felina. “He really personified what it meant to be a part of the neighborhood. He was lovely.”

Raquel, a Muffins employee who knew Theo for 25 years, said she’s going to miss him asking, “Who’s got my hot chocolate?” — his favorite menu item along with their lemon yogurt cake. Biba, the Muffins owner, told us, “Before he graduated to hot chocolate, he would get a coffee with a little milk and one sugar, and he would never want the, you know, the cup holder. He would always just want a couple of napkins.” She explained that Theo didn’t want a cup holder sleeve because he didn’t want to be conventional. Bibi, another Muffins employee who also works at their sister shop, Epices, was in the café that day and remembered how the children at Blessed Sacrament would always come running over to see him after school. She also pointed out Dixon’s style: “He was flying.”

ILTUWS’s contact info was shared in the group text of those who knew Theo. Susan Wands, who penned the Dixon biography and was a next-door neighbor of Theo’s, texted us, “When he first came to the block, people didn’t know quite what to make of this outspoken person who would cheer on children going to their first day of school in front of the Muffins Café. ‘You’re our future!’ he would tell children on their way to or from school. Children now going to college remember his cheering them on. Regardless of where they are living now, they think back to the times when Theo Dixon would tell them that they were our future. And now they are.”

Gabi Motintan texted us her favorite “Theo-isms” before mentioning how Theo helped her “adopted” grandma, Iuliana. “He would think of her as a mother figure, even his own mom. And he really played that role of protector.” She also noted that when Theo’s son, Scoop, would visit the Upper West Side, he too would help without hesitation. “Theo was indeed, through his actions, as big as his beautiful quotes!”

Steven Colbert of The Colbert Show actually ran from the stage during the taping of one of his episodes, when Theo was 98, to shake his hand and take a picture. Dixon, the veteran, was an audience member with Bellanich, who made sure to mention that Klein and Felice, currently abroad, are all kindred spirits and family who looked out for Theo — and vice versa. Katina Ellison, co-president of the 71st Street Block Association, told us, “Theo was one of the first and certainly the most loyal members of our block association, sometimes accompanying us to community board or police council meetings to share our concerns.” Ellison gave Theo some Greek worry beads, which he kept in his pocket at all times. “He clearly lived out that motto as he greeted everyone, including dogs, with warm and lively conversation! A light has gone out in our neighborhood, but his memory and words of love live on.”

Theo’s son, Scoop, currently in San Diego, said to us, “He will be dearly missed. He was my favorite mobster as far back as I can remember, and he’ll live on as the chief in my book.” He wanted to let everyone on the Upper West Side know, “Thank you for being a friend to him. He was loved and respected in the neighborhood because of people like you.”

Have a news tip? Send it to us here!