Missouri Rep. Tricia Byrnes (R-District 63) at a recently-held RECA panel, which included Dr. Amanda Moehlenpah, the RECA Program Manager from U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley’s (R-MO) office; Kisker Road Library Branch Manager Diana Tucker; St. Charles County Director of Elections Kurt Bahr and Recorder of Deeds Mary Dempsey. (Jessica Marie Baumgartner photo)

Jessica Marie Baumgartner photo

Roughly 10 years ago, Missouri Rep. Tricia Byrnes’ son, Chase, was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. Shocked by his diagnosis, she began asking questions about St. Louis’ radioactive past.

Could it be that his cancer was linked to where they lived? Byrnes felt certain that there was a connection to what was buried beneath the earth – and in St. Louis’ history – namely, uranium.

In early 1942, the entire world’s supply of refined uranium consisted of only a few ounces that would fit into a coffee cup, according to a 1996 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) report. But in 1942, the world was at war. Scientists with the Manhattan Engineering District Project were charged with producing the world’s first nuclear weapons. To do so, the scientists calculated that they would need 40 tons of uranium oxide and six tons of uranium metal.

Arthur Holly Compton, a Manhattan Project scientist and Nobel Prize-winning physicist from Washington University in St. Louis, thought he had a solution. He reached out to Edward Mallinckrodt Jr., president of Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, which had a reputation for producing pure chemicals.

In April 1942, Mallinckrodt agreed to help the federal government with its top-secret project. According to the USACE report, it was a handshake deal that was not officially finalized until much of the uranium for the Manhattan Project had already been produced by Mallinckrodt.

By July 1942, one ton (2,204.6 pounds) of pure uranium oxide was produced daily at Mallinckrodt’s facility on Destrehan Street in St. Louis. Between 1942 and 1957, the plant processed more than 50,000 tons of uranium product, according to the USACE website. With that uranium, Manhattan Project scientists achieved their goal: a self-sustained nuclear chain reaction. Their success enabled the federal government to build the atomic bombs that led to Japan’s 1945 surrender in World War II.

Seventy years later, Byrnes wondered if the fallout of World War II uranium production was still claiming lives. When her son’s cancer was diagnosed in 2016, she said she realized that “his chances of winning the lottery twice were better than his chances of getting that cancer.”

She was not alone in the fight. Over the years, residents with health concerns had repeatedly petitioned the federal government to take responsibility.

“My passion for helping them is why I went into office,” Byrnes said. “I had to do what it took in order to make a platform and make the noise we needed.”

Their advocacy and legislative efforts finally paid off in July when federal Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) coverage was expanded to include 21 ZIP codes in St. Louis and St. Charles counties. RECA was first authorized in 1990 to offer financial compensation to those in western states with adverse health effects from uranium mining or nearby atomic bomb testing. But the 1990 bill and future installments didn’t cover the St. Louis area.

“It’s not surprising that the act that is helping people in places like New Mexico and Nevada should also be helping St. Louisans, because they’re very much victims of the same atomic age,” said Don Corrigan, local environmental author and journalist. “I think St. Louis kind of gets lost in the shuffle. But in many ways, they are downwinders just like the people who were close to the atomic test. They may not have been present in the area of the nuclear test, but they were certainly downwind from radioactive contaminants that were dropped in their own neighborhood when the bomb was being developed.”

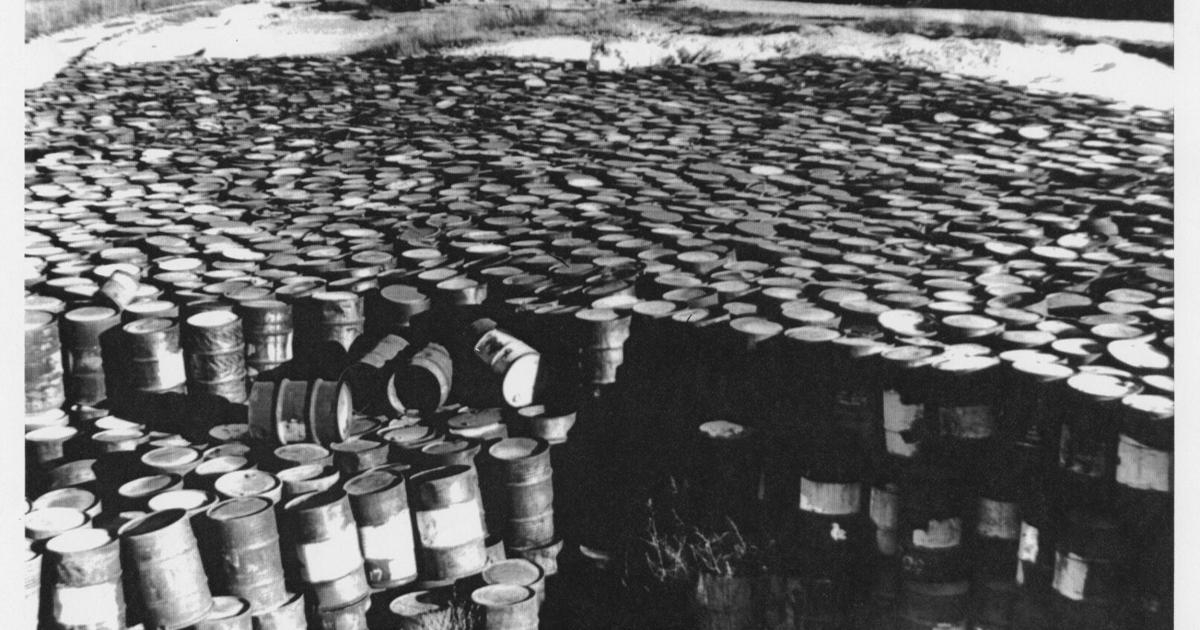

A photo taken in the 1960s of barrels filled with radioactive waste stored at the St. Louis Airport Storage Site (Photo courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection)

Photo courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection

Fighting for recognition

When Byrnes and other advocates were met with pushback, they pointed to federal documentation on the dangers of sites like and Mallinckrodt Chemical Company and the St. Louis Airport Storage Site (SLAPS or SLAPPS), which was used as a place to store residues from the Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, beginning in 1946.

“You want to prove this stuff kills people, they have their own data. They know exactly how this is killing their own workers. So if you’re a thousand feet from the same material, and you have the same injuries, it’s not much of a leap,” Byrnes said.

In 2023, Byrnes sponsored a resolution requesting the federal government to compensate Missourians affected by radioactive waste. In support of the legislation, she said nearly 200 people attended a 2023 Missouri House of Representatives committee hearing. Advocates and affected residents testified for about five hours in support of the resolution. It passed in the Missouri House and Senate.

“That committee hearing forever changed this for our region because it got the full support of Missouri behind us,” Byrnes said. “It felt like the mountain moved that day.”

Later that year, legislation sponsored by U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) to extend RECA coverage to St. Louis-area residents passed in the U.S. Senate but failed to make its way through the House. Hawley tried again in 2024, but that measure also failed. Finally, legislation to revive and expand RECA as part of the “One Big, Beautiful Bill” passed in July 2025.

“The federal government dumped nuclear waste in the backyards of Missourians for decades, and then lied about it,” Hawley said in a press release. “Reviving RECA means acknowledging the debts we owe these good Americans and delivering them the justice and overdue compensation they deserve.”

Like most St. Louis area residents, Byrnes had no idea that she had grown up and played in places contaminated with radioactive waste. Then, two of her playmates died from cancer, and her son was diagnosed.

In October, Byrnes hosted a meeting to provide information on applying for RECA. People who lived in the approved ZIP codes for at least two years and contracted certain cancers are eligible for financial compensation to offset medical expenses, and people who worked or attended school in these areas may be eligible.

Those who meet those criteria can learn more at justice.gov/civil/reca.

The threat didn’t end with World War II

Uranium production in St. Louis didn’t end with World War II.

“The ‘Cold War’ led to a build-up of nuclear arms in a race against the Soviet Union. The result of this new struggle to have the largest nuclear weapons stockpile again affected St. Louis,” the USACE report states.

It quotes Mallinckrodt Radiation Safety Officer Mont Mason as saying, “In the 24 years Mallinckrodt operated uranium facilities in St. Louis and St. Charles County, more than 3,300 employees produced in excess of 100,000 tons of purified natural uranium materials.”

In 1957, uranium processing was moved to the former Weldon Spring Ordnance Works in St. Charles County, which had been a U.S. Army TNT production site. Production happened at a chemical plant, and the resulting radioactive waste was disposed of in an abandoned rock quarry, all on about 230 acres. Waste byproduct called raffinate was also stored in four raffinate pits at the site. Production stopped in 1966, according to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

“During operations, the buildings, equipment, immediate terrain, process sewer system, and drainage easement to the Missouri River became contaminated with uranium, thorium and their decay products,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documents state.

Manhattan Project waste was stored at SLAPS on 21.7 acres of condemned land near Lambert Airport.

“The methodology for storing the waste at the SLAPSS was haphazard and would not be considered safe by today’s standards. Much of the waste was hauled by dump trucks to the SLAPSS and stored uncovered in piles. No consideration was given to controls for groundwater, surface water, exposure pathways, or other basic safety standards which are observed today,” the USACE report states. It adds that the workers’ understanding of the radiation danger was “incomprehensible” by today’s standards.

“One worker, uttering what has became (sic) a classic statement, is alleged to have said, ‘I don’t know what this stuff is, but they tell me it’s radioactive – so it must be for radios,’” the report states.

It adds that the attitude of the workers to radioactive materials was nonchalant, with workers handling it with bare hands and spilling uranium dust on themselves. So too was their handling of radioactive waste.

Coldwater Creek, Westlake & the Weldon Spring Remediation site

SLAPS was bordered by a railroad track, McDonnell Boulevard and Coldwater Creek. Wastes were discovered eroding into Coldwater Creek in the early 1980s, according to the report, and the DOE in 1985 constructed a gabion wall on the creek bank to prevent further erosion of waste into the creek.

In 1966, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, forerunner of the DOE, sold some of the material at SLAPS to the Continental Mining and Milling Co. The company transported some of the waste residues to a location about a half-mile away at 9200 Latty Avenue in Hazelwood, contaminating haul routes, according to the USACE report. This site became known as the Hazelwood Interim Storage Site (HISS).

Cotter Corporation purchased the remaining materials at HISS in 1969, about 115,200 tons of material according to the USACE. The company shipped most of the material to its mill in Colorado, leaving 8,700 tons of barium sulfate waste at the HISS site.

In 1973, Cotter Corp. dumped this waste on about 16 acres at the Westlake Landfill in St. Louis County, contaminating it and haul routes. The waste was diluted with an estimated 39,000 tons of topsoil, according to the USACE, and buried under three feet of soil.

“The transfer of the Cotter wastes to the Westlake Landfill was the culmination of almost 40 years of careless management, inadequate containment, and careless transportation practices,” the USACE report states. “The activities of this 40-year period resulted in the contamination of the banks of the Mississippi River, the river itself, numerous roadways and railroad right-of-ways, over 100 vicinity properties, a major urban stream (Coldwater Creek), and groundwater in the vicinity.”

The Weldon Spring quarry, chemical plant, and raffinate pits were added to the EPA’s National Priorities List in 1987. The SLDS site along with the SLAPS site and HISS site were added as the St. Louis sites in 1989, and the Westlake Landfill was added in 1990.

Excavation of the radiologically impacted material at the Westlake Landfill is expected to begin in 2027, according to an April EPA update. Remediation plans include excavating radiologically-impacted materials greater than 52.9 picocurries per gram generally down to 12 feet and transporting them to an off-site permitted disposal facility, according to the EPA. A landfill cover installation is also included in the plans.

At the St. Louis sites, remedial action at HISS was completed in 2013, and investigation and excavation are in progress at other areas, according to the EPA.

The planned remedy for the site includes excavation and disposal of contaminated soils, dredging contaminated sediments from Coldwater Creek and long-term groundwater monitoring in areas. The site is expected to be transferred to the Department of Energy’s Legacy Management Program in 2038, according to the EPA.

“That date marks the complete remediation of the site,” an April EPA update states, “as well as placement of land use controls on properties where accessibility did not allow complete cleanup to target levels.”

The Weldon Spring site was transferred to the Office of Legacy Management in 2003, according to the DOE.

“Remedial activities at the Chemical Plant and the Quarry have been completed with the exception of long-term groundwater restoration at both locations,” the EPA’s website states.

Groundwater is monitored at the site. The most recently published five-year review of the site showed the groundwater remedy is working as expected across the majority of the site, with the exception of uranium concentrations not decreasing in monitoring wells in two locations, according to the DOE. Concentrations are not increasing, and the water is contained to the wells, meaning residual contamination does not affect drinking water, according to DOE documents.

An on-site disposal cell was constructed to contain the site’s contaminated waste.

“The 41-acre disposal cell completely secures the waste materials, which are solid, dense, and tightly compacted,” a DOE frequently asked questions document for the site states. “The system was designed to last for 1,000 years, but in reality, the construction materials and technologies extend the cell’s life for much longer.”

Eighty years after uranium first flowed from Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, the contamination it left behind is still being uncovered, cleaned and contested. But Byrnes said there is work still to be done.

Although affected regional residents can now seek financial relief under RECA, she said, more ZIP codes and diseases need to be added to the next installment of RECA.

“We need more advocates and more people who are going to be outspoken,” she said. “Our foot is in the door for RECA. That took decades. Now the hardest part is over.”