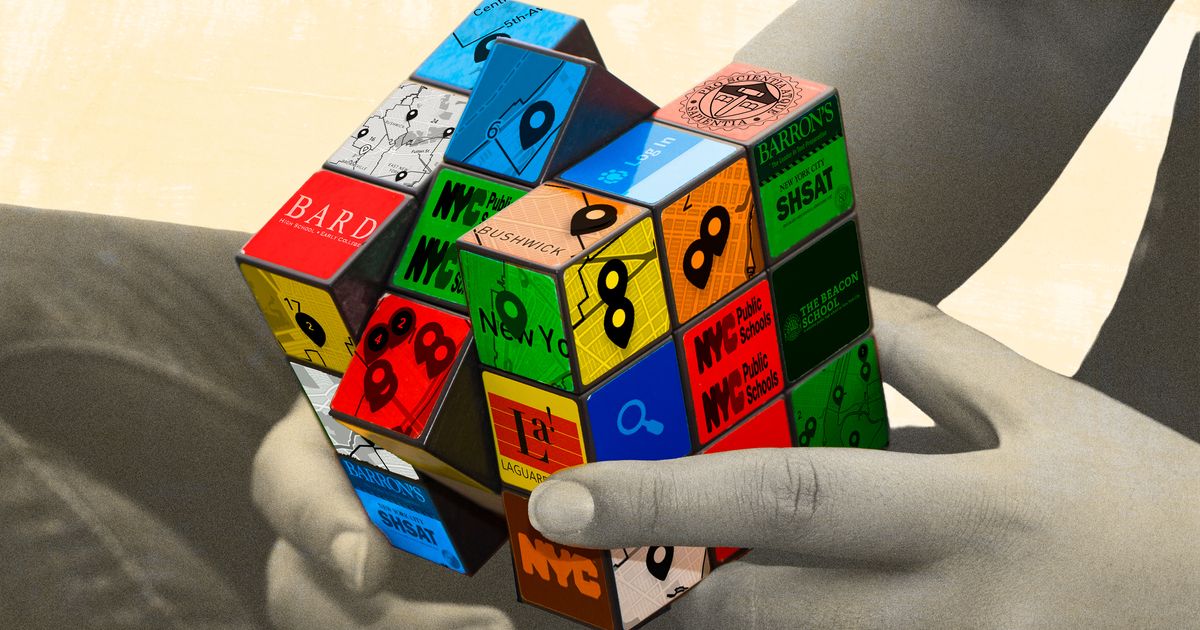

Photo-Illustration: The Cut; Source Pphoto Getty Images

Being furloughed without pay through October and most of November was a nightmare for federal workers across the U.S. But for Emma, who lives in Chelsea with her twin eighth-graders (and asked to use a pseudonym), the break had a silver lining: It gave her the time she needed — though many parents might argue that no amount of time is truly enough — for the singularly painstaking task of applying to New York City’s public high schools.

In some American cities, teenagers seeking a specific curriculum have the option of applying to high schools in lieu of going to the one closest to their home. Only in New York is this process the standard operating procedure for every public school student. The city’s public-education system houses seven categories of admission methods with strangely opaque labels: specialized, screened, screened with assessment, audition, ed opt, open, and zoned. In total, these labels encompass more than 400 schools and more than 900 specific school programs. (A single school can contain multiple programs, each with different pathways to entry.) Building a list of preferred choices — the city’s Department of Education strongly suggests ranking 12, but this year, for the first time, students can rank more — demands and rewards parents who have the time, know-how, and sheer force of will to navigate a labyrinth of madness.

For Emma, the first minute or two of the process went smoothly. On October 7, she logged in to the portal and discovered that both her daughters had been assigned favorable lottery numbers, known as RANs (an abbreviation for “random numbers”). Each RAN is 32 digits long, but inexplicably, only the first two numbers and letters in the sequence matter. Then she looked up her children’s SAGs (for “screened admissions group”), which is based on the average of their grades in English, math, science, and social studies in seventh grade. There are four SAGs, and to get into the much sought-after SAG 1, which grants applicants their first pick of high schools, students must be in the top 15 percent of seventh-graders. This year, that meant earning an average of 94.33 or higher. Emma’s daughters, Sara and Catherine (both pseudonyms), had worked doggedly over the past year and were stellar students at their middle school. But only Sara made SAG 1. Catherine missed the cutoff, with an average of 93.

Emma felt her chest tighten. Twins are allowed to apply to high schools as a unit but being in different SAGs meant the two girls were unlikely to receive the same offer. “One has access to a certain segment of schools that the other one doesn’t,” she explained in tearful disbelief weeks later. “I mean, who would think that a 93 average would not be good enough to get you into these same schools?” Emma’s daughters had been in school together since they were toddlers, so the prospect of spending the next four years apart would be an adjustment for everyone in the family. It has also required Emma to research many more schools than she had originally planned to. When we first spoke in late October, she was signed up for 18 in-person tours.

“I don’t know how I would manage this and work full time,” she told me. She knows being an involved parent can make a significant difference in helping her children find schools where they’ll thrive, which, for many parents, also means gaining admission to a top college. Still, this knowledge fails to make muscling through the ordeal any easier. Although the admissions process for the specialized elite schools like Stuyvesant and Bronx Science tends to dominate headlines about high school in New York, the order of operations for average kids is a trial of its own — one that’s arguably even more difficult to maneuver.

There are a few helpful resources for parents navigating the process. The New York City Public Schools site and a school-finder tool called NYC-SIFT, which was created by New York dad Adrian Liang when one of his children was applying to high school two years ago, contain information on all the schools’ demographics and graduation rates, and both have admissions-predictor tools that take a child’s SAG, RAN, and address into account to help them decipher where they’ll likely get in. But many parents told me that getting through the process confidently was really only possible thanks to the wisdom and emotional support they found in the Applying to High School in NYC Facebook group. It has over 16,000 members and five moderators, all of whom are veterans of the application procedure. The page was founded in 2021 “on a whim” by Leslie Rubin, a mother navigating the application system at the height of the COVID lockdown. In the realm of parental Facebook groups, which can be snake pits of sanctimony, judgment and flexing, this one is an oasis. “There is a culture here that embraces being really kind, passionate, and devoted to always learning new nuances of this crazy process,” the moderators said to me in a communally written email.

Posts go up multiple times an hour, all seeking opinions and advice on everything from basic definitions of DOE terminology to how to rank a list of schools for a particular kid to whether the accommodations and services promised to students with disabilities or individualized education plans live up to their stated promises. The process is full of bewildering exceptions and seemingly unsolvable conundrums. For example, to promote academic diversity, ed opt (short for educational option) programs save one-third of their seats for students in equal measure grouped into three buckets based on their grade point average in seventh grade. As one parent explained, it’s not unlike the student-body makeup, in an academic sense, of a typical suburban public high school. But parents comparing these schools to screened options sometimes question whether their SAG 1 or SAG 2 child’s academic experience could be compromised by remedial learners. (In the Facebook group, other parents regularly chime in to assure them this is not the case). New York also has open and zoned schools, where admission may be strictly RAN-based, open to anyone throughout the city, or prioritize students with specific addresses. At some screened schools, SAG and RAN numbers determine the priority with which applicants will get seats — SAG 1 students are considered first, and if there are more applicants in the group than available seats, offers are determined by their RAN. But there are anomalies among these schools, too.

This year, the iSchool in Soho, which has around 470 students, has abandoned SAG numbers in favor of its own process, which requires students to submit a short essay expressing their specific interest in the program. Beacon, a self-described “selective” high school in Hell’s Kitchen; Bard, an early-college high school with campuses in Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens; and a small handful of other schools also require additional essays and assessments on top of the standard application. At Bard, when an applicant scores high enough on their Bard-specific assessment, they get invited in for an interview, the results of which are weighed much more heavily than the student’s SAG number.

Still other schools, like the famous La Guardia High School of Music and Art on the Upper West Side (and other fine- and performing-arts schools), require applicants to submit an audition video or a visual portfolio and don’t look at students’ RAN or SAG numbers at all. The same goes for the city’s eight specialized high schools, including Brooklyn Tech, Bronx Science, and Stuyvesant High School. There, admission is based solely on the results of the three-hour SHSAT exam, which covers both English and math skills. (Registration for the test closed on October 31, and scores will be released on March 7.)

Last year, of the approximately 26,000 eighth-graders who took the test, only about 4,000 received a school offer. For some students, the process gives a reprieve from the somewhat arbitrary SAG cutoffs. But of course, it’s also unfair in a way all its own. Those who have access to SHSAT prep tutors (a parent in Harlem told me she was quoted $10,000 for a test-prep course) have the advantage. The city also offers a free SHSAT intensive in the spring and fall on Saturdays and a five-week SHSAT intensive camp over the summer, called the DREAM program, but it’s available only to applicants who meet a certain minimum grade-point average as well as household income or neighborhood requirements. And even then, there are no guarantees. Last year, only 3 percent of specialized-school offers went to Black students, and just 6.9 percent went to Hispanic students.

Ian an attempt to describe what the process has been like, Melissa, a mom in Brooklyn, told me, “It’s like trying to explain what an anxiety attack feels like with someone who has never had one before.” Her daughter is a vocalist casting a wide net. She auditioned for performing-arts schools like La Guardia and Frank Sinatra in Queens and applied to a mix of screened and ed opt schools, including Richard R. Green, which offers both a teacher-preparation academy and a liberal-arts academy in the Financial District, and University Neighborhood, an early-college high school on the Lower East Side that has both ed opt and screened pathways to admission.

“You have to ask your own questions and be your own thinker and be adventurous enough to really go outside of the lines,” Melissa told me. She says she sees many kids apply to the same ten or so schools, largely because they’ve heard other kids are applying to them — which gives the schools a kind of tacit endorsement.

Emma’s daughters have wildly different interests. Catherine wants to study filmmaking, while Sara hopes to attend a school specializing in STEM. Their enthusiasm for the admissions process has also been uneven. Emma told me that Catherine, who is in SAG 2, was willing to participate in the open houses, while Sara, who struggles with anxiety, was fairly deferential to her mom. “I really have to drag Sara to some of these open houses. She’s like, ‘I just want science, Mom, and no sports.’” To attend tours and open houses, eighth-graders often have to miss parts of their school day and give up their evenings and weekend afternoons, even when they have homework and SHSAT studying to do.

Many take a multipronged approach — auditioning, taking the SHSATs, and writing essays for screened schools. Some students who audition or assemble portfolios intend to pursue art as a career, but others are well aware that it’s not their lifelong interest. Still, they want the option of an arts-focused high school because the instruction and environment may be superior to other schools.

Arie, an eighth-grader in Brooklyn who has dyslexia, is auditioning for the theater program at La Guardia and studying for the SHSAT (he wants to go to Brooklyn Tech). He’s also very busy preparing for his bar mitzvah. “My main thing is that I want a school that gives me more advanced stuff than my middle school does. But if I do wind up going to a more academic school, I want opportunities for me to still do art stuff,” he explained. He said he and his parents are aligned on the schools he has ranked but the workload has been stressful for him.

I also spoke with Max, an eighth-grader in Manhattan who loves to draw and play violin. He was in the midst of assembling a visual portfolio, which required a still-life of three objects, a self-portrait, and a figure drawing, all in graphite, as well as something La Guardia calls a “fantastical sandwich.” The application prompts the student to fill a page with a drawing of the most bizarre sandwich (and the scenario in which it would exist) they can imagine. Max was still in the planning stages when we spoke in October. He told me his ultimate goal for high school is to end up at a place “where I’m going to enjoy it and have friends and do well.”

Then there’s Connor, an eighth-grader in Queens who doesn’t know whether college is in his future and therefore has his own definition of what makes a school “the best.” Having been in Catholic school all his life, he is going to public school for the first time, so he’s approaching his search with making new friends in mind (few of his classmates are following his path). He is prioritizing schools with vibrant student clubs and schools that are a short subway or bus ride from his home. He also wants a strong career- or technical-education program that centers on his interests — architecture, construction, and veterinary science. “I really want to work at something where AI can’t take my job,” he told me. When I spoke to Connor and his mother, they were quibbling over which school to rank as his first choice. He likes John Bowne High School, an ed opt school in Flushing with an animal, plant, and agriscience institute, but his mom, Wendy, “can’t stop talking about” Newtown High School, a zoned school in Elmhurst that has pre-engineering, architecture, and HVAC-installation programs. “Newtown has a lot of the programs that can lead him into either a trade or something outside of college that he could fall back on if he doesn’t choose the college route,” Wendy said.

As for Emma, after investigating more than 30 schools — in the end, she saw 22 in person and eight online — both girls’ lists changed considerably. Schools with good reputations, even the specialized ones, were not as compelling as others they saw. “Some of the smaller, more ‘prestigious’ schools were also not as interesting as I expected,” she said. She was particularly struck by how few schools had an art requirement or a dedicated artmaking space.

The application portal closes today, and the high schools will all send out their offer letters on March 5, 2026. After that, families navigate the wait lists. “This can be an almost nine- or even ten-month process,” said Lisa Leingang, a Manhattan mom who went through it two years ago. “My daughter got offers off the wait list in July.” In other words, the end of the application process is both near and far.

Still, parents told me there’s considerable comfort in knowing the open houses are over, the SHSATs and other assessments have been taken, and the auditions and portfolios are complete. Emma and her daughters settled on their lists of schools — each girl is ranking nine, a mix of screened and ed opt, with three or four overlaps between them. They feel good about their choices, and with the government shutdown finally over, Emma has returned to work. Life is almost back to normal.

But it has been a very long, very draining fall. “I’m so exhausted I feel like I’m going to cry all the time. I actually started taking medication for anxiety due to this process,” said Emma. “I don’t think I will fully relax until March, when the offers are made.”

Related