Man Ray: Forme di Luce

Palazzo Reale

September 24, 2025–January 11, 2026

Milan

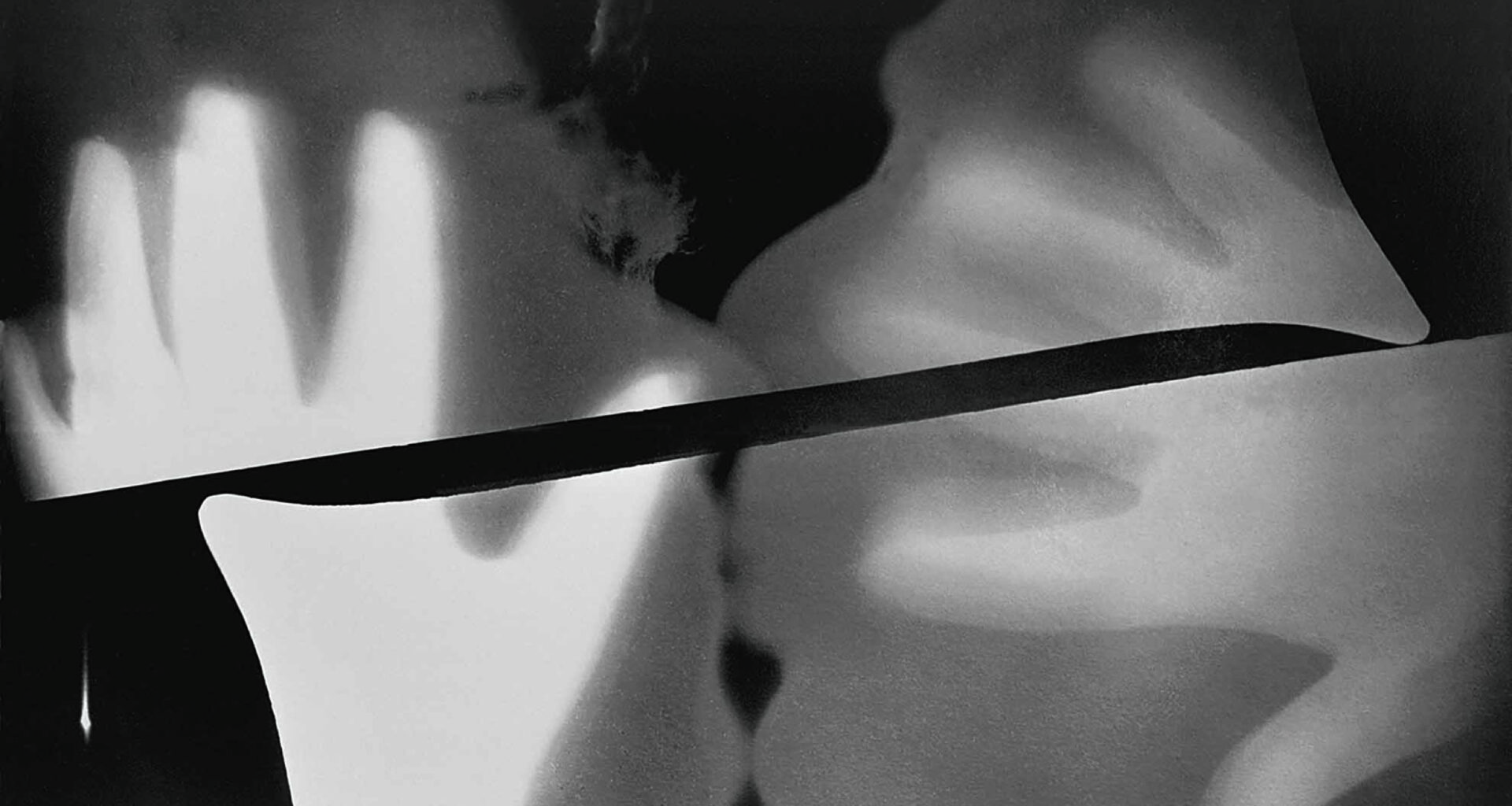

“Many so-called tricks of today become the truths of tomorrow,” wrote Man Ray (1890–1976) in his autobiography. Indeed they do, and nowhere more than in the domain of photography, whose practitioners are constantly coming up with new ways (and reasons) to do old things. Take the much-ballyhooed Rayograph, so-named by Man Ray, who also renamed himself, leaving behind the more ethnic (and Jewish) Pennsylvania birth name Emmanuel Radnitzky. The process—performed by interposing an object between a light source and a sensitized piece of paper and exposing it to create a reverse or negative silhouette—has been around since the birth of the medium, as the photogram. Actually before it, for it requires no camera. It remains with us still, as artists at key moments throughout the history of the medium have resorted to it. The question, always, is why?

Just as the same question is prompted by two major Man Ray exhibitions at the same time, in Milan and New York’s Metropolitan Museum (Man Ray: When Objects Dream) both focusing on his photography. Or rather, why now? This review focuses on the Italian version, but it’s worthwhile making a few broad comparisons. The Met exhibition is both narrower in temporal scope, reaching only to 1931, and more ambitious in art historical attention. Milan is more of a crowd-pleaser. At the Met, an extensive sample of Rayographs stands at the center of a complex argument, linking photography to Man Ray’s other explorations of dimensionality in collage, sculpture and painting. At the same time, the exhibition emphasizes his links to Surrealism and suggests that photography was a way to manifest unconscious desires and manipulate the body in two dimensions. No question that from the moment he met Marcel Duchamp in 1915, Man Ray was committed to the pursuit of surprise and pleasure in his art, and like Duchamp, with whom he would remain friends throughout his life, he was also committed to independence, expressed as artistic game playing. When Duchamp first visited him at his house in New Jersey, the two spoke no common language and so amused themselves, at Man Ray’s instigation, by playing a game of tennis with no net Man Ray imbibed, borrowed, played with whatever intrigued him, made friends in a Parisian milieu that included Dadaists and Surrealists, and avoided the internecine strife. As he writes, “My neutral position was invaluable to all.”

So was his photography. He began to take photographs initially as documentation of his and other artists’ work. Most famously, he photographed Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-23) in long exposure and low angle. This resulted in a purely “factual” but indecipherable image, a lesson about photographic mystery he never forgot. In Paris, copy work would help support him as he tried to set his feet in a competitive art world where he did not speak the language (but one much more likely to appreciate his work than the United States, from which he departed in 1921). Not surprisingly, neither Milan or New York offered examples of his quotidian stuff, except for the image described above. He also began to take photographic portraits of his friends, lovers, and acquaintances. He was fascinated by the appearances of people, especially artists, as if their faces and bearing were somehow clues, and for the next two decades he photographed almost everyone who was anyone, from Duchamp to James Joyce to a nearly deceased Marcel Proust. The exhibition at Palazzo Reale centered on these portraits (minus, alas, the Proust), set up almost as an autobiography of Man Ray. The prints came from a mishmash of sources and iterations, leading to an unevenness in the presentation that made it difficult to put one’s hands on the past, so to speak, but their importance was clear. Man Ray drew a line between most of this work—commercial and ultimately repetitive—and his “art,” yet he constantly sought to import his discoveries in the darkroom and studio into this work. Some results are goofy, like the image of a nude Lee Miller, herself a photographer and Man Ray’s lover, with a metal mesh lampshade for headgear (ca. 1930). Some are happy mistakes in line with the Surrealists’ devotion to chance. The Marquise Casati loved a blurred portrait showing her with four eyes (1922), the result of an unintended long exposure. And some push a strategy to the point of revelation, as in Man Ray’s portrait of composer Igor Stravinsky (1925), caught in an out of focus instant of motion gazing skyward, as if contemplating unseen forces.