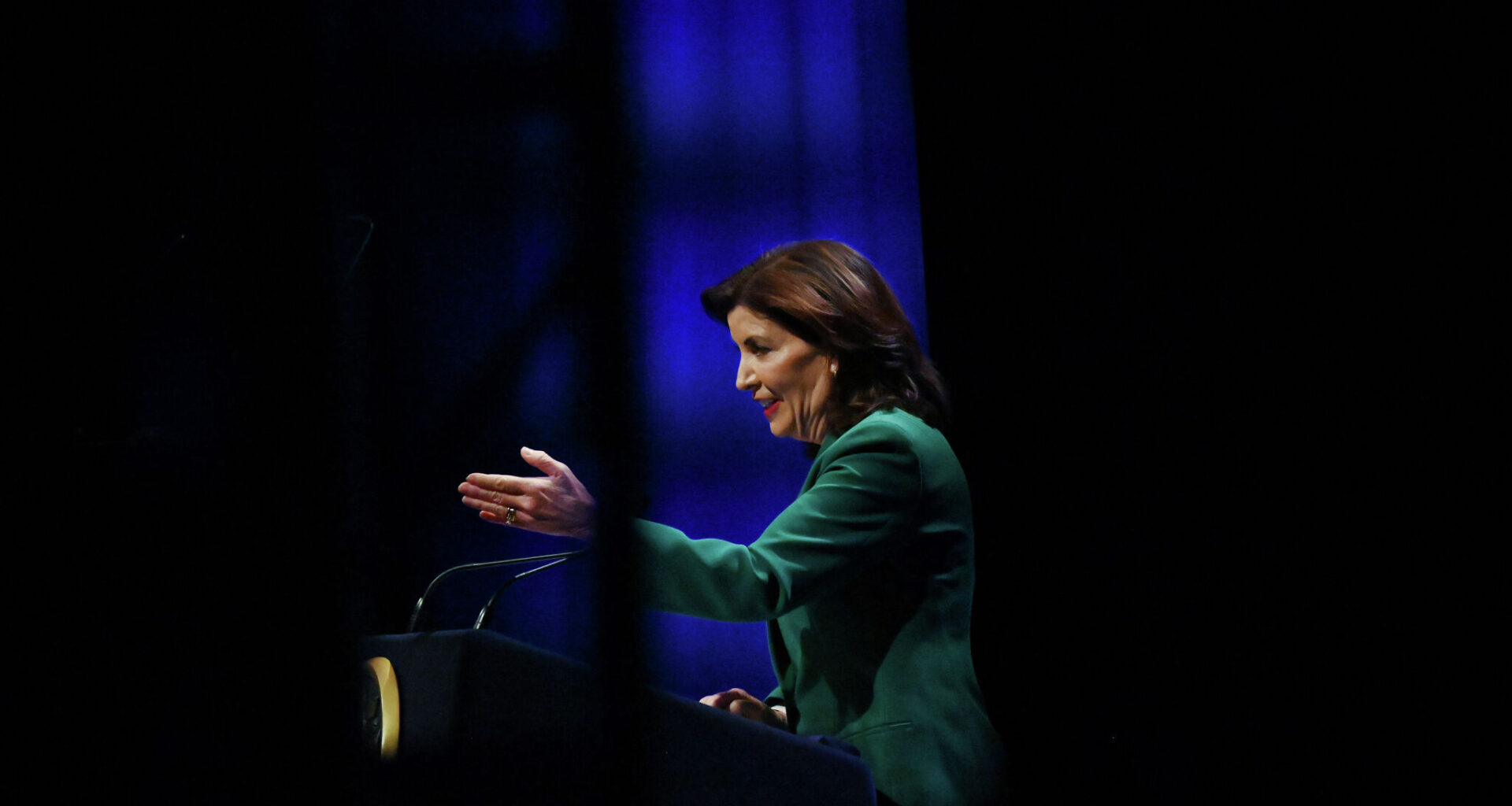

Gov. Kathy Hochul grabbed headlines in November for saying that North Country Rep. and likely gubernatorial candidate Elise Stefanik was “full of sh–.” (Will Waldron/Times Union)

Will Waldron | Times Union/Times Union

ALBANY — Lawmakers mincing words in Albany? You’ve lost your damn mind.

Don’t expect to hear New York senators and Assembly members say “darn it,” “straight to heck,” or “H.E. double hockey sticks” in the opulent surroundings of the historic Capitol.

Article continues below this ad

In Albany, you’ll occasionally hear an elected official use more colorful rhetoric, including a four-letter word that shares letters with and rhymes with fire truck.

“Damn” appears to be the most commonly used curse word during the last two legislative sessions, and lawmakers here are fond of using “crap” to describe things they don’t like, according to a review of committee meetings and floor debates.

Sometimes the colorful language spills into the Assembly chamber or other official gatherings, including when Gov. Kathy Hochul said that “rent is too damn high” during her most recent State of the State address in January. In her speech, Hochul also recounted the last phone call with her father before he died. She was on her way to Israel after the Oct. 7 attacks, and he told her to “keep your goddamn head down.”

Make the Times Union a Preferred Source on Google to see more of our journalism when you search.

Add Preferred Source

In April, during last session’s contentious budget debate, Republican Assemblyman Chris Tague raised his voice to harp on New York democracy, or an apparent lack thereof, after Democrats refused to call a floor vote on a bill meant to strengthen partnerships between community colleges and the private sector.

Article continues below this ad

“And you all talk about democracy,” Tague said. “Democracy, my ass. Democracy, my ass. I will say it again.”

Profanity in politics isn’t as taboo as it once was, although there have been many notable pottymouths stretching back to the nation’s founding fathers. John Adams, the nation’s second president, memorably referred to Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. secretary of the treasury, as a “bastard brat” during the throes of their bitter political rivalry.

And who could forget presidents Lyndon B. Johnson’s and Richard Nixon’s extensive use of profanity, revealed through White House tapes.

In Albany, New York governors, many of whom have had their political careers burst into flames, have also been known through the years to let curses fly, especially in private settings.

Article continues below this ad

Former Gov. Eliot Spitzer used explicit language to describe his governing style early in his tenure, calling himself a “f—ing steamroller.” Andrew M. Cuomo was also known to use coarse language and to berate staff.

Former Gov. Eliot Spitzer used explicit language to describe his governing style early in his tenure, calling himself a “f—ing steamroller.”

Stephen Chernin | AP Photo/AP

But their salty rhetoric was often largely out of the public’s view.

In the Assembly during the last two legislative sessions, only one lawmaker used profanity that would violate the Federal Communications Commission standards, the Times Union found. That was Assemblyman Edward Gibbs, a Manhattan Democrat.

Article continues below this ad

Gibbs’ remarks came during a May 14 hearing on safety, transparency and accountability within state correctional facilities. The first formerly incarcerated person to serve in the state Legislature, Gibbs used five choice four-letter words as he described the violence, racism and lack of accountability that he said continues to define New York’s prison system.

“I’m getting all the f—ing questions out,” he said.

E.J. McMahon, an adjunct fellow at the Manhattan Institute and founder of the Empire Center for Public Policy, has worked in Albany as a policy analyst for the last three decades and covered Albany politics as a reporter and columnist in the 1970s.

He said that in years past, it was rare, if ever, to hear a politician curse, even in private. He doesn’t like the shift in language.

Article continues below this ad

“This is cringe,” McMahon said. “It ain’t pleasant. They think it’s the only way to be authentic, but it’s simple-minded. They demean themselves and lower the tone of political discourse that is low enough already.”

Political pottymouths on the rise?

There’s some evidence to suggest that public swearing by politicians has risen since around 2015. It has likely been influenced by the rise of social media platforms such as Twitter, which became a political tool that shifted discourse during President Donald J. Trump’s inaugural campaign for president, said Ben Bergan, an associate dean of the school of social sciences at the University of California San Diego. He is also the author of the 2016 book “What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains and Ourselves.”

Bergan said that the public may be more desensitized as foul language has permeated cable television shows, podcasts, satellite radio and even the “mainstream media.”

Article continues below this ad

During a May hearing on correctional facilities, Assemblyman Edward Gibbs, center, used curse words to describe his opinion of the violence, racism and lack of accountability in New York’s prison system.

Will Waldron | Times Union/Times Union

“In general, the run of the mill profanity — the ‘f— s,’ the ‘sh–s’ and things that these politicians are now producing — is judged to be less offensive now than it was,” Bergan said. “And that’s probably part and parcel of this prevalence of profanity in public discourse.”

Younger, less religious, city dwellers tend to be less offended by profanity, making it a potentially effective way for politicians to sound more relatable to certain groups, he added.

“Politicians often try to seem similar to their electorate,” Bergan said. “To the extent that they are speaking to an electorate who uses informal language, including profanity, and the way that’s reflected in what they see in the politician, that can be effective.”

Article continues below this ad

But spicy language can also be used as political fodder.

In May, author Michael Levin penned a column for Fox News with the headline, “What the F—? Democrats turn to profanity instead of policy.” Levin said the party was embracing profanity as a way to try and reconnect with voters after heavy losses in the 2024 presidential election.

“The Democrats would be better advised to stop trying to sound authentic and start trying to figure out why they should remain in business,” Levin wrote.

U.S. Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer, who two years ago said he was “shocked” by reports of a Republican lawmaker cursing out teenage Senate pages, has more recently raised eyebrows for his use of coarse language.

Article continues below this ad

In an August interview with Aaron Parnas, the New York senator said there was “no f—ing way” Congress would approve an extension of Trump’s deployment of National Guard troops in Washington, D.C. He used the phrase again in October in a video he posted on X in which he said Democrats would not agree to end the shutdown of the federal government.

U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who in 2020 took to the House floor to admonish vulgar insults hurled at her from a Republican lawmaker from Florida, has herself had some notable outbursts.

That same year, the congresswoman who represents parts of the Bronx and Queens flung curses Trump’s way in a Vanity Fair interview for his alleged tax maneuvers and revelations in the New York Times that he had only paid $750 in federal income taxes.

“These are the same people saying that we can’t have tuition-free public colleges because there’s no money, when these motherf—–s are only paying $750 a year in taxes,” Ocasio-Cortez said.

Article continues below this ad

Trump, born and raised in Queens, emphatically dropped the f-bomb on camera in June when he expressed frustration that Israel and Iran appeared to be violating a ceasefire he helped broker. While Trump has been known to use vulgarities in speeches and other public appearances, his deliberate use of the f-word broke a presidential norm, NPR reported.

Before that, the word was most commonly dropped on a hot mic when presidents didn’t know they were being recorded. When touring hurricane damage in 2022, former President Joe Biden was caught saying, “No one f—s with a Biden.”

McMahon characterized politicians’ use of curse words as a performance.

Consider Schumer, he said, who has been in public life almost his entire adult life and had once been carefully disciplined and conditioned not to use vulgarities in public.

Article continues below this ad

“So when he uses vulgarity in public, he’s making a conscious decision to break with a 50-year-old habit for effect because apparently it is being seen as something one does,” McMahon said. “I just think it’s a negative thing. One should not commend or smile at this. Who are you trying to impress? You know better.”

Profanity and the race for governor

Hochul’s cursing should not come as a surprise. According to a recent analysis from the word wizards at WordTips, the city of Buffalo, which is Hochul’s hometown, is among the most foul-mouthed cities in the country.

State Senate Minority Leader Rob Oritt, who represents nearby Niagara County, has demonstrated that cursing can be bipartisan. Last year, in an Instagram post, Ortt said, “I am damn proud to be an American” as he expressed pride in his military service.

Article continues below this ad

After Hochul killed a special elections bill in February that would have allowed her and future governors to delay congressional and state elections until November during vacancies, Ortt said that Democrats were “full of sh–.”

“Damn” appears to be Hochul’s favorite curse word and she uses it often on social media.

Last year, in an Instagram post, state Senate Minority Leader Rob Ortt, center, said, “I am damn proud to be an American” when discussing his military service.

Will Waldron | Times Union/Times Union

Republican U.S. Rep. Elise Stefanik, who is running for governor, doesn’t appear to curse in her social media posts or public comments. However, the congresswoman is no stranger to name-calling. She’s doubled down on her characterization of New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamani as a “jihadist,” accusing him of harboring antisemitic views.

Article continues below this ad

In response, Hochul grabbed headlines in November for saying that Stefanik was “full of sh–” in a live interview on MS NOW. Hochul’s campaign has repeated the phrase in campaign text messages.

Swearing also interacts with gender expectations, Bergan said. Women are judged more harshly than men for using the same profane language.

Because Hochul has presented herself as a mature womanly figure, there might be an “extra element of shock when she says something like ‘sh–,’” said Julie Novkov, dean of the University at Albany’s Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy.

“’Damn’ won’t raise a lot of eyebrows, but if you get into ‘sh–‘ and ‘f-bombs,’ depending on the person and public persona, that’s going to create a lot more emphasis,” Novkov said.

Article continues below this ad

Should both candidates become their party’s nominee, Novkov said, it will be interesting to see how Hochul and Stefanik navigate gendered expectations for what a woman can and cannot say in politics, and what happens if they intentionally break that norm.

Stefanik finds herself in a difficult situation because she will have to “be a bit of a fire breather to resonate with the most activated Republicans in the state,” said Novkov.

That may accumulate a record that will then be easy for Democrats in the general election to play clips of her saying things that resonate with the hardcore Republican base but don’t with broader New York and the country, Novkov said.

Article continues below this ad

There’s some science to back that up. According to Bergan, swearing can sometimes influence how the public perceives a speaker in ways that may help or hurt a politician.

“From a variety of studies, we know that when a person swears, others judge that person to be more honest,” he said. “They also judge that person to be less well-educated. They judge them to be less of a rule follower. All of those things could play into, positively or negatively, the kind of image that a politician or any public figure is trying to engender.”