This article was produced as part of the New York Jewish Week’s Teen Journalism Fellowship, a program that works with Jewish teens around New York City to report on issues that affect their lives.

On her Uber app, Sivan’s name is Alexandra. Noa tells people her name is Nina. Michal goes by Micky in car services and when ordering coffee.

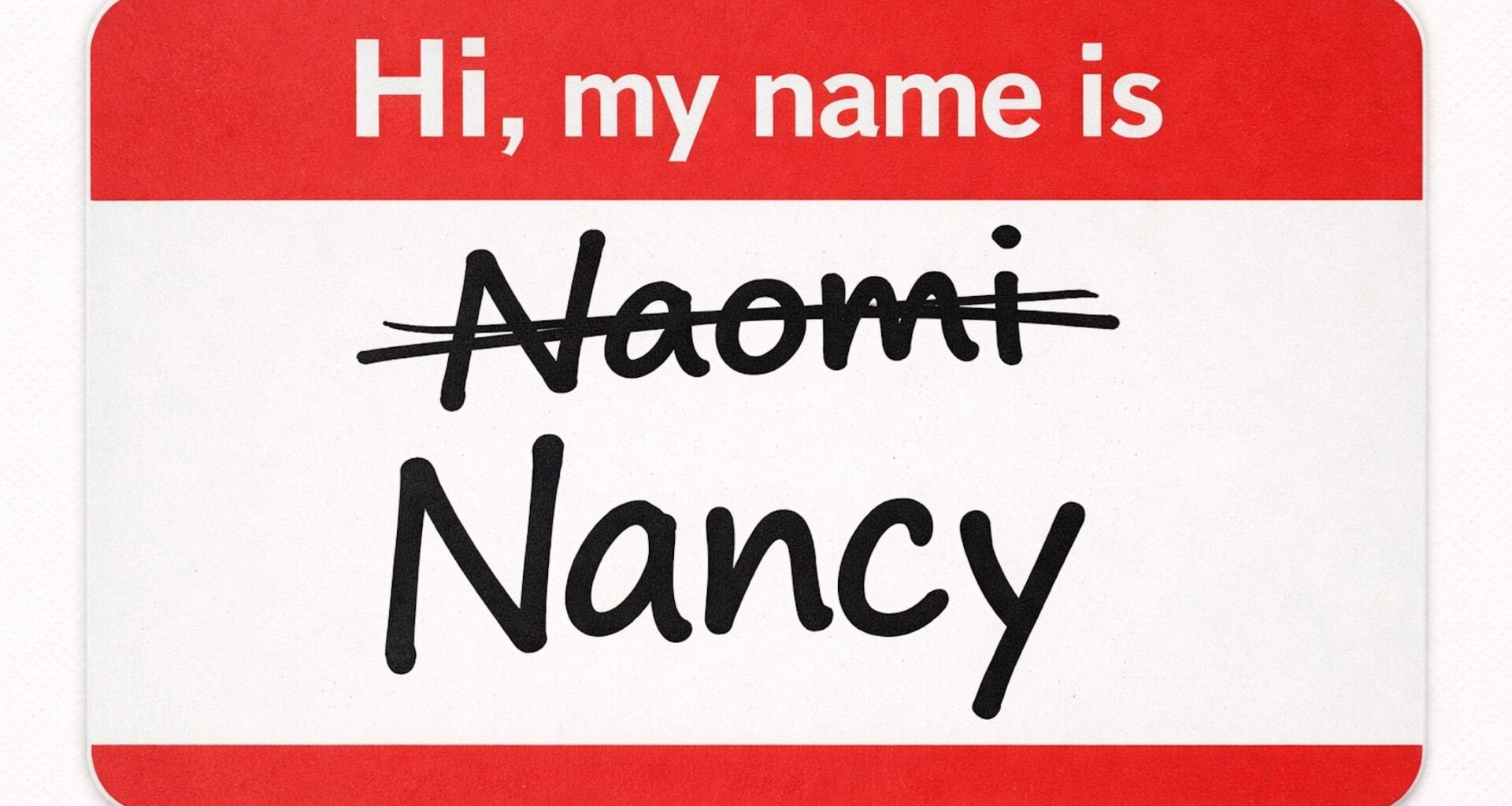

These days, some New Yorkers with Jewish-sounding names are providing fake names when they interact with strangers. They say the motivation is to feel safer around town, given the spike in antisemitism in New York City and elsewhere after Oct. 7. Most wish they didn’t have to hide an important part of themselves, but they do so to protect themselves physically and emotionally.

Sivan, 19, who attended private high school in Manhattan, decided to start using a non-Hebrew name right after Oct 7. She made the decision after hearing a story from her friend, Ellie, who said she was asked by an Uber driver if she was Jewish. When Ellie, to be safe, reflexively lied and said, the driver allegedly responded: “Good, because if you were I would have killed you.”

“I was scared,” said Sivan, who started using her middle name when calling a car service. “It was the first time in my life I was really scared to be Jewish. I had always learned about the Holocaust, but I never thought it would be me.”

“It makes me sad that we live in a world where you can’t use your name because you’re scared of being killed,” Sivan added. (While real first names are used in this article, the interviewees requested that any personal identifying information, including their last names, not be published, highlighting just how unsafe some Jewish teens in New York City feel.)

This year alone, the Anti-Defamation League reported over 1,000 antisemitic incidents in New York City – the highest count of antisemitic incidents in any U.S. city since the organization began recording these instances in 1979. Specifically, the report showed a spike in antisemitism and harsh anti-Israel rhetoric targeting those who are visibly Jewish.

Antisemitism is hardly a problem exclusive to New York City. More than half of Jewish Americans report experiencing some form of antisemitism last year (2024-2025). The ADL reports that antisemitic incidents in the USA hit a new high in 2024 — more than 25 antisemitic incidents a day.

Recently, the Slovakian-Canadian model Miriam Mottova was kicked out of an Uber in Toronto after the driver assumed Mottova was Jewish based on a phone call she was having in the car. According to Mottova, the driver said she “does not drive Jewish people.” Since going public with her story, Mottova claims that “scores of people” have reached out to her with similar stories about Uber.

Last year, Lindsay Friedmann, the New Orleans-based director of the ADL’s South Central Region, “received reports of Uber drivers canceling rides after learning their passengers were Jewish or refusing to drive to Jewish locations,” according to The Media Line. Many of those masking their Jewish identities were students at Tulane University.

Friedmann, too, shortened her name on her Uber profile, using only her last initial. According to the publication, a ride with “a driver displaying a Palestinian flag confirmed her decision.”

While neither Uber nor Lyft has a phone number riders can call if they experience harassment, riders can file complaints on the car services’ apps. According to an Uber spokesperson, “our specialized teams carefully review reports of this nature and take appropriate action, which includes removing individuals from the platform.”

In New York, despite regulations meant to protect New York City residents from “prejudice, intolerance, bigotry, and discrimination, bias-related violence or harassment,” many Jewish teens living in New York City feel unsafe. According to an ADL report from October, the antisemitic trends in 2025 “provide evidence of a sustained pattern of harassment, intimidation and violence that threatens Jewish New Yorkers’ sense of safety and belonging.”

A Washington Post poll conducted in early September found that about 42% of Jewish Americans reported avoiding publicly wearing, carrying or displaying anything that might identify them as Jewish in the previous year, a notable rise from similar questions in earlier years.

The issue is a family matter for 14-year-old Rowan, an eighth grader who lives in Yorkville, and his mom, Michal. Michal recently heard a story about an Uber driver who asked a friend’s teenager if he was Jewish; when the son lied and said “no” to avoid any confrontation, the driver revealed he would have kicked the friend out if he was.

Rowan does not feel a need to hide his name because it is not a typical Jewish-sounding name. His mom still advises him to remain vigilant for his safety and not to invite problems by revealing his Jewish identity.

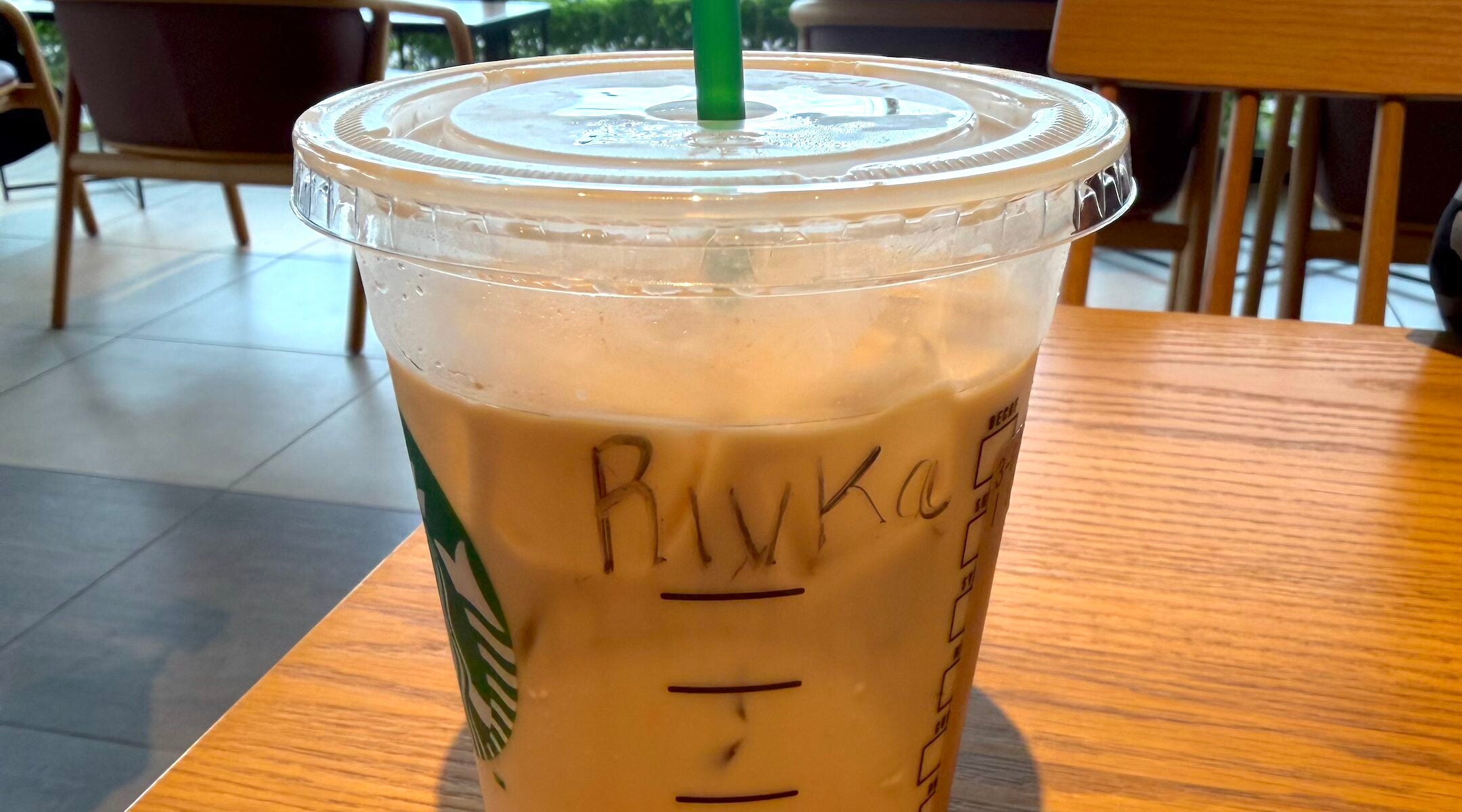

Rather than hide her Jewish identity, Rebecca said she’ll use the Hebrew version of her name when ordering coffee in order to make a statement against antisemitism. (Courtesy)

“If anyone asks if he’s Jewish, he should say no,” Michal said she told her son, who uses Ubers frequently with friends. “I’d rather [he] be safe than have pride, or do whatever [he] thinks is the right thing.” As for her own safety, Michal uses the name Micky in car services and in coffee shops.

Michal has also urged Rowan not to display his Star of David on sidewalks and subways for fear of violence. Rowan partly agrees with his mom. “I understand why my mom asked me to hide my Magen David necklace. It’s not right to have to repress your identity, but also you don’t want to put yourself in danger,” he says.

The decision to hide her real name was not an easy one for Sivan, who was named, in part, after her great-uncle Sonny. Normally, her name — Hebrew for “season” and the ninth month on the Jewish calendar — serves as a conversation starter. “I can make immediate connections with people when they learn my name,” she said. “It’s obviously a very Jewish-sounding name.”

Meanwhile, Sivan’s sister, Noa, 24, uses the name Nina when she takes a car service in New York City. “When I would go into an Uber and they would see a girl with my name and no ‘H,’ it was kind of obvious it was a very Israeli name,” she said.

Families anglicizing their Jewish-sounding names is not a new phenomenon, of course. For hundreds of years Jews in New York City have changed their names to avoid prejudice. By 1932, nearly 65% of name-changes in New York City were requested by Jewish families, many of whom were hoping to provide opportunities for their children and prevent harassment, especially in schools, according to Kirsten Lise Fermaglich in her 2018 book, “A Rosenberg by Any Other Name.”

Notably, generations of Jews believed — and some still believe — that their names were altered on Ellis Island as a clerical error or “easy shorthand.” Scholars have shown that Ellis Island clerks did not have the ability to change last names, leading some authors — including the novelist and essayist Dara Horn — to argue that Jews perpetuated this myth to mask the shame of having obscured their Jewish identity.

But not all people feel the need to adopt non-Jewish sounding pseudonyms. Rebecca, 20, who was living on the Upper East Side when Oct. 7 broke out, said that since then she sometimes takes the opposite approach: She deliberately uses her Hebrew name in public. “If I go into a Starbucks and hear something antisemitic, I would say my name is Rivka,” said Rebecca. (Immediately following Oct. 7, Starbucks Workers United – which includes employees in many New York City locations – took to social media to celebrate Hamas, voice solidarity with Palestine and condemn Israel. Starbucks quickly disavowed the union’s statements.)

Another teen boy, who asked to remain anonymous for fear his speaking out would impact his future, said that even after being thrown out of an Uber with his dad on the Upper East Side on Yom Kippur this fall because the driver discovered they were Jewish, he refuses to “closet” his Jewish identity and that tie to his family and cultural history.

“I use my name because in the Jewish religion it acknowledges the individuality of each person,” he said. “It makes you, you.”

Being named after his great-grandfather, he feels a deep connection to his own name. He added: “He might not be with us in body, but he can live on in spirit — and through my name.”