I first came to know the Adirondack Mountains as a hiker and quickly became obsessed with the place. It is a disease, I have learned, that also afflicted the John Brown family in the 1850s. They called it “Essex fever.”

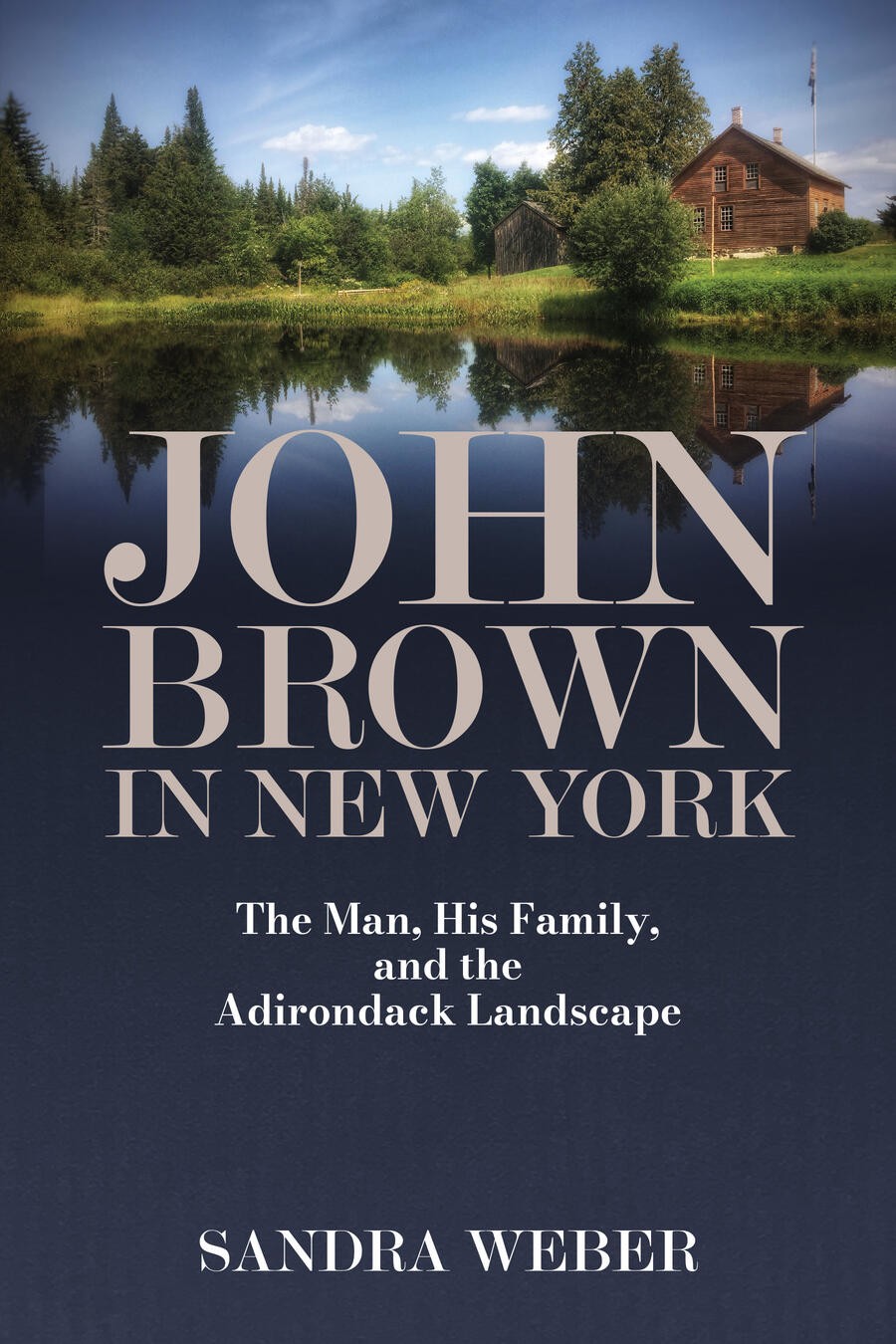

My fever spread from hiking to history to writing. Soon, I made my first foray into book writing, which went merrily astray. Like my subject, Esther Combs, I lost my direction, wandered through the trees, and landed in an unexpected place. Yet, we both were brave and kept following our dream. And now, many books and many years later, I still find my writing going astray, as it did with my latest book, “John Brown in New York: The Man, His Family, and the Adirondack Landscape.”

My focus has tended toward the women of the Adirondack peaks, from Esther Mountain to Mount Jo (Josephine/Jane Scofield), Mount Inez (Inez Milholland), and Grace Peak (Grace Hudowalski). I also wrote about the untold and un-promoted stories of Adirondack women, such as abolitionist Mary Brown, writer/lecturer/reformer Kate Field and photographer Katherine McClelland. Those three remarkable women prompted my entry into the labyrinth of John Brown history. For two decades, I managed to stick to those women and avoid the muddled maze, or so I thought. Then, it dawned on me that Mary had been misleading me; I had strayed right into the trap.

Without realizing it, I had come to know John Brown, the man, through the eyes of his wife. Once again, I had followed a herd path and landed in an unexpected place: writing a John Brown biography.

Sandra Weber shares how she came to author “John Brown in New York.” Photo provided by Sandra Weber.

Sandra Weber shares how she came to author “John Brown in New York.” Photo provided by Sandra Weber.

It was a humungous task unlike anything I had ever attempted. There was so much material to digest. So many details to analyze, theories to scrutinize, questions to answer. So much puffery and fake news to slog through. The more I learned, the more I knew I needed to learn more. Month by month, the Adirondack perspective of John Brown became clearer, the book’s purpose grew stronger and my uncertainty turned to conviction.

Eventually, as I completed the last of several revisions, a tagline revealed itself: who he is in the Adirondacks is who he is.

That is precisely what Mary Brown showed me. When asked if her husband was insane, Mary said, “I couldn’t say…that my husband was insane—even to save his life; because he wasn’t.” Another time, she said that if John were insane, “he had been consistent in his insanity from the very first moment she knew him.”

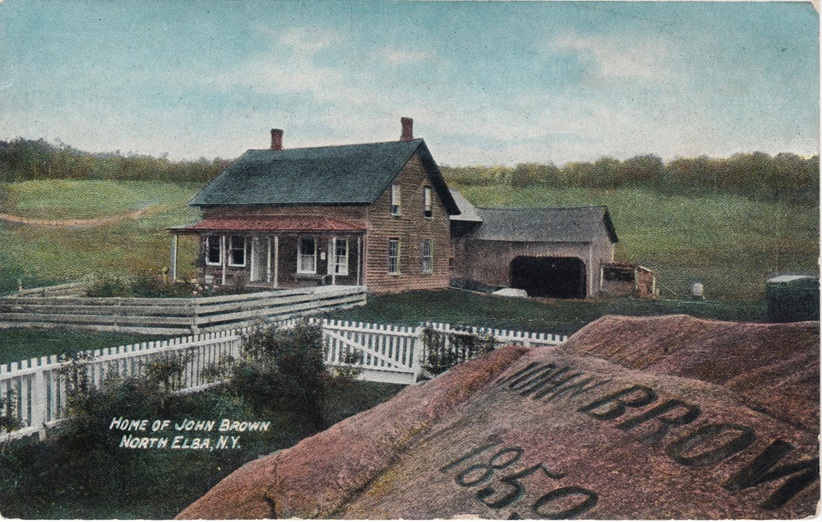

John Brown’s actions and words and convictions at Kansas and Harpers Ferry were consistent with his North Elba character. He believed in the words of the Bible, the Golden Rule and the Declaration of Independence—and put them into daily practice. He was a family patriarch, good Christian, common farmer and helpful neighbor with extraordinary egalitarianism and moral virtues. He hated oppression, injustice and slavery. He loved family, God and country and was willing to sacrifice comfort, safety and life to execute his duty and responsibility. Wealth, fame and power held no appeal for him. John Brown was not confused or duplicitous or erratic; his conscience was clear.

However, in big actions as in small deeds, John Brown had a propensity for delay, a quirky sense of humor, an endless supply of optimism and a heap of advice in even the tiniest details. He delayed his move to the Adirondacks in 1849, and his return in 1855. As Adirondack winter set in, he suggested the Black settlers should “busy themselves in cutting plenty of hard wood…they need not fear getting too much wood provided.” (No joke in the Adirondacks.) When he was away from home, he often wrote to those in North Elba: “try to be cheerful,” “hope in God” and “encourage each other.” That could be difficult at times; son Owen said, “on the 6th of June we could not clear away the manure from the Barn because it was half Ice yet.”

When John Brown discussed placement of his house, he suggested it be level with, or even below, the water source. “I would be at a good deal of pains to avoid lugging water up a steep place,” he said. He also wanted his house “to stand square with the world, longest East and West with doors opening through it North and South.” (Quintessential John Brown.) To keep the cold out of the new house, John suggested son Watson cover the exterior with “cheap straight-edged boards.” He advised him to run the boards from the ground to the eaves “barn fashion” and hammer the nails only partway so the boards could be removed later and re-used.

Brown stood frugal, and resolute. He intended to bring a lawsuit to recover a $3 tax he paid on grazing land (even though the lawyer fees might amount to $10.) He told son Wason how to sign a money draft (“across the back…about two inches from the top end”) and Mary how to mail letters (“I need not say, do all your directing and sealing at home, and not at the post-office.”) Even while preparing for his greatest action in Harpers Ferry, John inquired about the crops at the farm and asked the women to help the boys pick up stones and sticks on the meadows before the grass grew too high. He also instructed them to sow cloverseed and Hungarian grass seed on 1/16 of an acre as an experiment, which he would never see to fruition.

What occurred in the Adirondacks would resound in Harpers Ferry. In one of her final letters to her husband, Mary Brown wrote: “You know that Moses was not allowed to go into the land of Canaan; so you are not allowed to see your desire carried out.” Virginia hanged John Brown on December 2, 1859. Nevertheless, the seeds he planted would culminate in the freeing of millions of enslaved people.

For more information about “John Brown in New York: The Man, His Family, and the Adirondack Landscape” and the author, see John Brown in New York preview and www.johnbrownNY.com.