You know him from his classic hits of the ’50s and ’60s, both with his early group the Belmonts and later on his own: “I Wonder Why,” “A Teenager in Love,” “Runaround Sue,” “The Wanderer,’ “Ruby Baby,” “Donna the Prima Donna” and many others. But Dion DiMucci, born in The Bronx, New York, on July 18, 1939, is still going strong; he never allowed himself to become an oldies act and has continued exploring new avenues for his music.

Over the past several years, that has meant putting together albums of duets, mostly within the blues genre, with artists he loves and who grew up on his music. Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1989—the fourth class, along with heavyweights like Stevie Wonder and the Rolling Stones—Dion, who usually goes simply by his first name professionally, has often been dubbed “The King of the New York Streets.” He lives in Florida now, but he retains that swagger that he fostered back in the day. Simply put, he’s about as cool as cool gets.

On the eve of the release of his latest album, 2025’s The Rock ‘n’ Roll Philosopher (a companion to his book of the same title), Best Classic Bands spoke with Dion, one of the last remaining survivors among the great early rockers, about those early years and what he’s up to now.

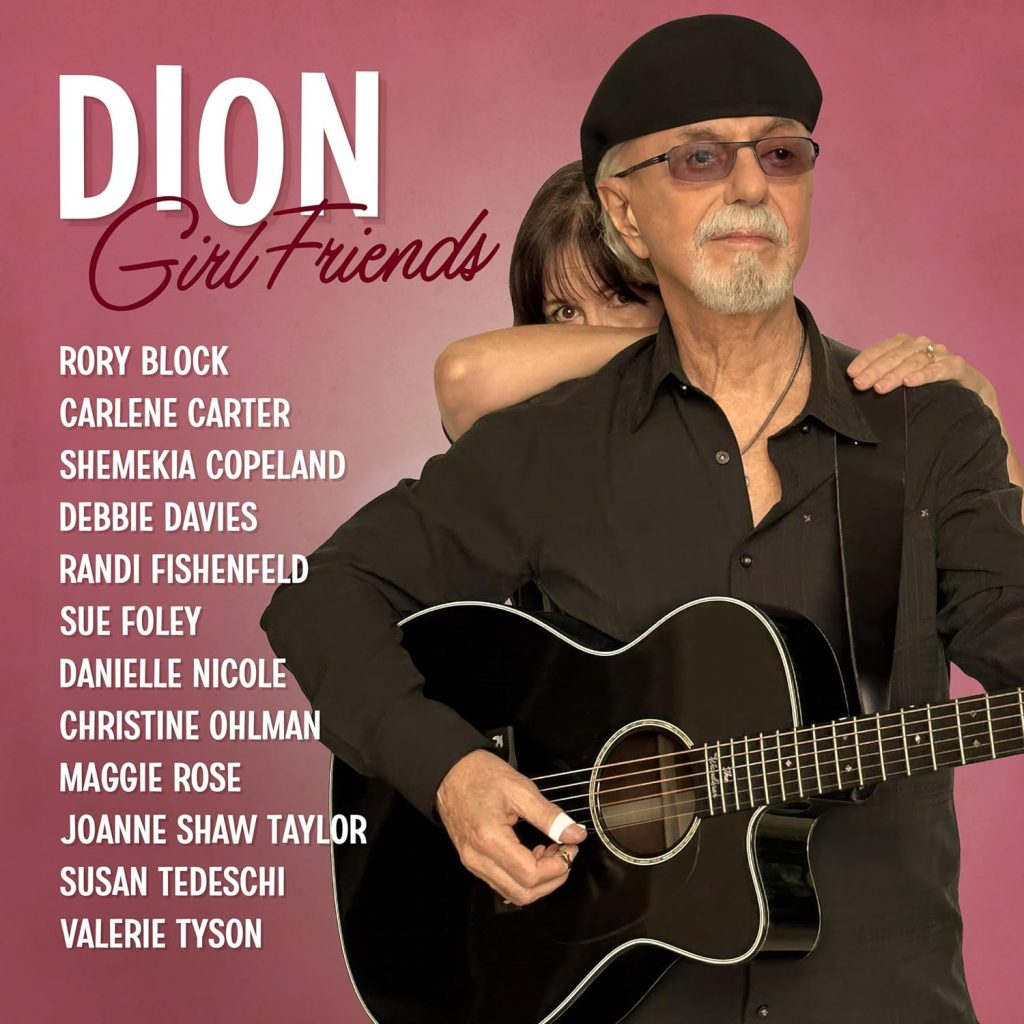

Best Classic Bands: You’re midway into your 80s and still making new music. In 2020 and 2021, you made the albums Blues With Friends and Stomping Ground, which included collaborations with people like the late Jeff Beck, Billy Gibbons, Van Morrison, Peter Frampton, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and Eric Clapton. Your most recent album, 2024’s Girl Friends, features you working with all women artists, including Susan Tedeschi, Carlene Carter, Shemekia Copeland and several others. How did that one come about?

Best Classic Bands: You’re midway into your 80s and still making new music. In 2020 and 2021, you made the albums Blues With Friends and Stomping Ground, which included collaborations with people like the late Jeff Beck, Billy Gibbons, Van Morrison, Peter Frampton, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and Eric Clapton. Your most recent album, 2024’s Girl Friends, features you working with all women artists, including Susan Tedeschi, Carlene Carter, Shemekia Copeland and several others. How did that one come about?

Dion: With Blues With Friends, I worked with [singer-songwriter-guitarist] Samantha Fish, and it was so much fun working with her. I just loved it. And then on Stomping Ground, I worked with Rickie Lee Jones, which was a trip, and Patti Scialfa. So I came up with this idea. I listen to a lot of music, so I know what people are doing and I know who I like and I know who has soul and I know what I’m listening for. Like, I love the way Susan Tedeschi sings. We made a pact that we’re going to do something vocally together. I started writing songs, and I thought, I’m gonna write songs across the table. I’m talking to these women in all different situations.

Related: Our review of Girl Friends

Is it more challenging to write for a woman’s point of view and for a female voice?

It’s funny. I never thought of writing for a female’s voice. As far as the songs were concerned, no. It gave me new energy and a new creativity to take it from a different angle, to write from another person’s view, and then I’m talking back and she talks back. It’s like a conversation.

Listen to “Soul Force” with Susan Tedeschi from Girl Friends

How do you approach performing with somebody that you’ve never sung with before?

Usually I hear the person that I want to be on the song. For instance, I wrote a song called “Dancing Girl.” I heard Mark Knopfler on it immediately. Jeff Beck was the only guitar player that can make me cry, so he’s gotta go on the ballad. I never thought of asking for help. I used to do everything myself. God forbid I should ask for help.

Watch Dion and Jeff Beck perform “Can’t Start Over Again” from the Blues With Friends album

You’ve been a blues fan since your childhood. But you also listened to country, which nobody would expect of a kid growing up in The Bronx. How were you finding these songs back then?

I got fixated on a radio station out of Newark [WAAT] that played Hank Williams. I used to record the shows on a tape recorder. It took me to a place of enchantment, something I wasn’t experiencing in my home. My parents were always arguing and this thing transcended what I was experiencing. I used to run home from junior high school to get the last half hour of that show. In fact, I called [the disc jockey, Don Larkin] once. I found out he was living in Arizona. This was a while ago. He was an old man.

Watch a rare clip of Dion and the Belmonts performing “Ruby Baby” in the early ’60s

It’s often been said that blues and country music are two sides of the same coin.

Yeah, absolutely. The way I see it is that you take blues and you take country, you get rock and roll out of it. It’s rock. The blues turns into a major key, and then you get “The Wanderer.” You get attitude and all that stuff. I’ve always loved the blues because it has an element to it that I call bragging rights. I love those kind of songs. They’re so over the top, and such fun to sing.

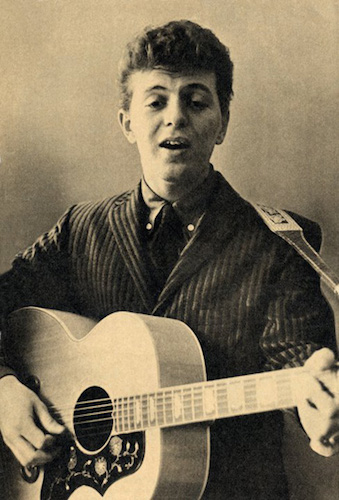

Dion in the ’60s (Photo from his website)

So you’re in your room listening to Hank Williams and blues records, and then you’re on the street corner singing doo-wop. Did your friends think, what the hell’s up with this guy?

Well, the thing is, I was never purely doo-wop, but I could get into it. I could get into anything as long as it was good. But I really liked [bluesman] Jimmy Reed. “The Wanderer” or “Ruby Baby,” some of those songs, I used to cop the sax riffs at the Apollo [Theater in Harlem] and just put ’em behind what I was doing. I guess they called it doo-wop, but I used to be creative with the guys on the street, guys’ voices. I used to give them parts, like in “Runaround Sue.” I would cop the riffs, and just give it to the guys.

Did you ever play the Apollo yourself?

Yeah. Oh, it was great. They loved us, man. They loved us. They just took to us, man. “I Wonder Why,” they loved. And they loved the backside of it, “No One Knows.” They loved that. People don’t know this, but at the Apollo, we were doing a rendition of “Honky Tonk.”

The 1956 Bill Doggett hit?

Yeah, an instrumental, with guitars. [Belmonts members] Carlo [Mastrangelo] was a great drummer, and Angelo [D’Aleo] could play bass. We would do this stuff. So we had a good time there.

How did you make that transition from a guy listening to this music coming over the radio to doing it yourself and actually getting discovered?

I couldn’t plan it if I tried. I was just into Hank Williams. I knew a lot of his songs. I knew all his Luke the Drifter songs. [Note: Luke the Drifter was an alias sometimes used by Williams.] I’ve been trying to recreate Jimmy Reed and Hank Williams and transmit that feeling to other people.

Listen to Dion sing Robert Johnson’s “Travelin’ Riverside Blues”

Was there a single moment when you knew this was what you were going to do with your life?

That music jumped out of the radio and embraced me, man. I knew it was serious. I was serious. I’m singing at the local dance or here and there, I’m not thinking of anything other than that. And this guy in the neighborhood said, “I’d like to take you down to a record company that started up. It’s in Manhattan.” So I went down there and I played a few songs for them, and they signed me immediately. They called my parents; I was 17.

Yeah. And off we went. They put me with a group called the Timberlands. They were so hokey. They were like theatrical singers, like “Oklahoma.” I said, “Nah, nah, nah, nah. If you want me to sing with guys, I’ll go back to my neighborhood. I’ll recruit some guys. I know guys who sing up at the pool rooms.” So I got the three best singers I knew and I brought them down there, and that’s how Dion and the Belmonts started up.

When you look back at those early records, do they still hold up for you?

It’s a funny thing. I was always so down on the song “Teenager in Love.” You can’t sing it at my age. But we had a play on Broadway [The Wanderer], and there’s a scene where the girl who plays my wife, she sings “Teenager in Love,” acapella. And, oh my God. I was sitting in the audience and I said, “I really understand what this song is about.” Now, after singing it all these years, for some reason she made it make sense to me. And I felt good that I sang it.

Dion (l.) with Doc Pomus (Photo courtesy of Dion)

You were close to Doc Pomus, who co-wrote that song with Mort Shuman. What was Doc like?

He was the greatest. I have a picture of me and him. He was like my dad. I met him with Mort. I love Shuman and Doc. Doc Pomus kind of took me under his wing and took the place of my dad. Like I had a second chance of growing up.

After the Laurie sides, you went to Columbia Records and had some more hits and then, for most of us, you disappeared for a while. I know you were having some rough times. How did you pick yourself up and get out of that?

Well, I was very addicted. I was a junkie in the mid-’60s. I was using heroin for about 14 years. I used to hang out with Frankie Lymon. We used to do drugs, unfortunately, and, he died in February of 1968. That’s what got me strong. You realize that drugs and alcohol have nothing to do with being creative. They’ll just kill you. And I know that because the last three or four years, I’ve written 30 of the best songs I’ve ever written. So it has nothing to do with drugs or anything.

I want to ask about your wife, Susan. When you came out with “Runaround Sue,” did she say, “Hey, man, how about making that Runaround Barbara”?

That’s a strange thing, that song, because I didn’t know Susan too long at the time. And it just landed right, the name. Barbara wouldn’t have. It’s kind of a funny situation. I always loved the song, especially when I was on the streets doing it. When I made the record, the guys in the neighborhood said, “You ruined it.” It was so good at parties and stuff. It was so raw.

When you look back at pictures and videos of yourself from that period, do you relate to that guy? Do you look at the 25-year-old Dion and go, who is that guy?

Well, there’s something about the young kid that’s still in there. But I’ve changed. My friends in California, they go, “You reinvented yourself.” I go, “No, no, no. I didn’t.” First of all, I didn’t create myself in the first place, so I’m not gonna recreate myself. I said, “I’m just evolving. I’m developing. That’s all. I’m maturing.”

The only time I really felt that you were recreating yourself was in 1968 when you came out with “Abraham, Martin and John.” Most of us hadn’t seen you since you had a big pompadour and here you are singing this serious song and you’re wearing John Lennon glasses. Is that really the same guy? It was just a different kind of vibe.

The only time I really felt that you were recreating yourself was in 1968 when you came out with “Abraham, Martin and John.” Most of us hadn’t seen you since you had a big pompadour and here you are singing this serious song and you’re wearing John Lennon glasses. Is that really the same guy? It was just a different kind of vibe.

Even when I played “Purple Haze” for Jimi Hendrix, I was frightened of what he might say. But he said, “No, you’re going to the same place I’m going. It’s just a different approach.”

Related: The story of “Abraham, Martin and John”

I’ve never heard the word retirement come out of your mouth. Is that off the table for you?

If you are looking to retire you’ve probably been in the wrong job. I do what I love now. I was never really a road guy, that I had to be on the road, although I love the audiences and performing; it’s a lot of fun. But I just like creating. I talked about this to Frankie Valli. I don’t think he wrote a song, but I like putting something there that’s never been there. I like creating something that never was physically. It’s in your head.

Watch the official music video for “Abraham, Martin and John,” filmed in 2025 for the new Dion album, The Rock ‘n’ Roll Philosopher

Dion published his book The Rock ‘n’ Roll Philosopher in early 2025. It’s available in the U.S. here, in Canada here in the U.K. here. The companion album, of the same title, will be released on October 24, 2025. It’s available for pre-order in the U.S. here, in Canada here and in the U.K. here.

Best Classic Bands Editor Jeff Tamarkin has been a prolific music journalist for nearly five decades. He is formerly the editor of Goldmine, CMJ and Relix magazines, has written for dozens of other publications and has authored liner notes for more than 80 CDs. Jeff has also served on the Nominating Committee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and as a consultant to the Grammys. His first book was ‘Got a Revolution! The Turbulent Flight of Jefferson Airplane.’ He is also the co-author of ‘Shell Shocked: My Life with the Turtles, Flo and Eddie, and Frank Zappa, etc.,’ with Howard Kaylan, and ‘Carlos Santana: Love, Devotion, Surrender: The Illustrated Story of Santana’s Musical Journey.’

Latest posts by Jeff Tamarkin (see all)

Latest posts by Jeff Tamarkin (see all)