Aldrich Ames, a CIA counterintelligence officer who committed one of the most damaging breaches in US history by selling out nearly a dozen Soviet, Russian and other officials working for the West, died Monday at the Maryland federal prison where he was serving a life sentence.

He was 84.

Ames pleaded guilty in 1994 to conspiracy to commit espionage and tax evasion, admitting to being paid at least $2.5 million by Moscow in exchange for US secrets between 1985 and Feb. 21, 1994, the day he was arrested outside his Arlington, Va. home.

At the time of his arrest, Ames had been working for the agency for 31 years and had been posted to some of the most sensitive areas of the Cold War — including Turkey, New York, Mexico City, and Rome.

The turncoat’s disclosures to Moscow included the identities of 10 Russian officials and one Eastern European who were spying for the United States or Great Britain — along with spy satellite operations, eavesdropping and general espionage procedures.

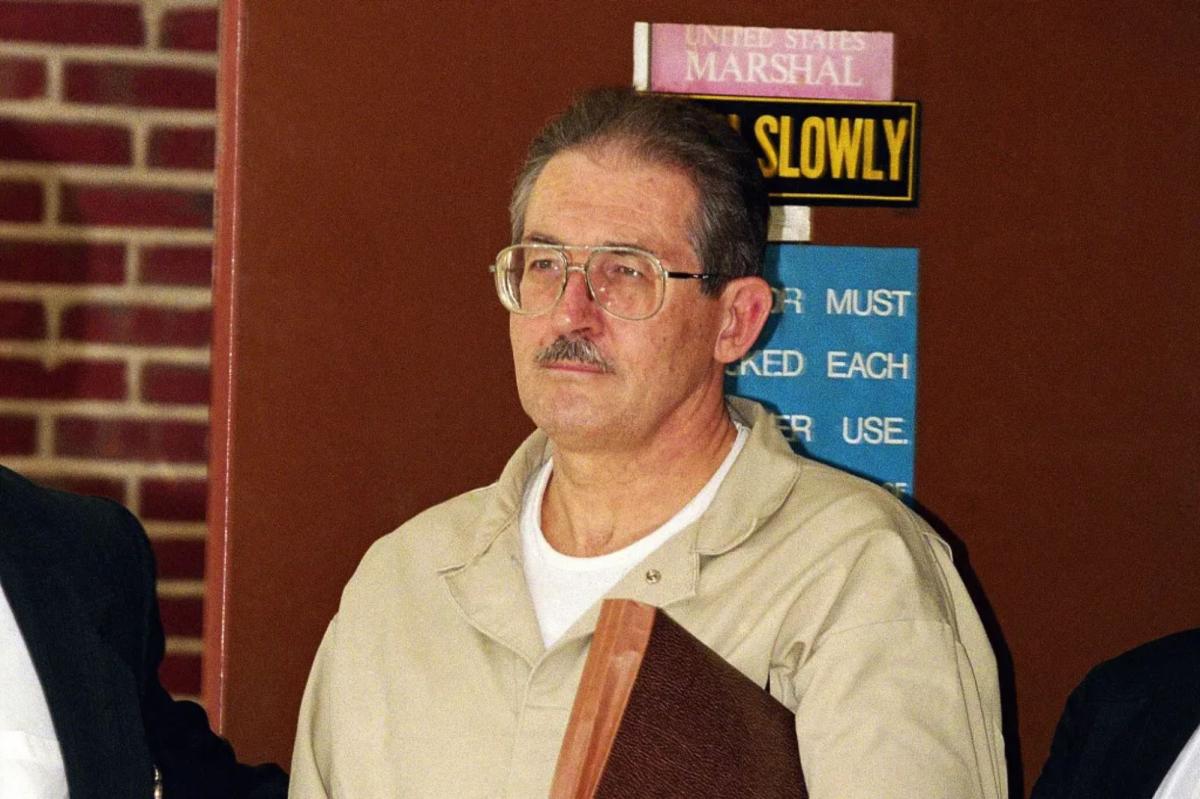

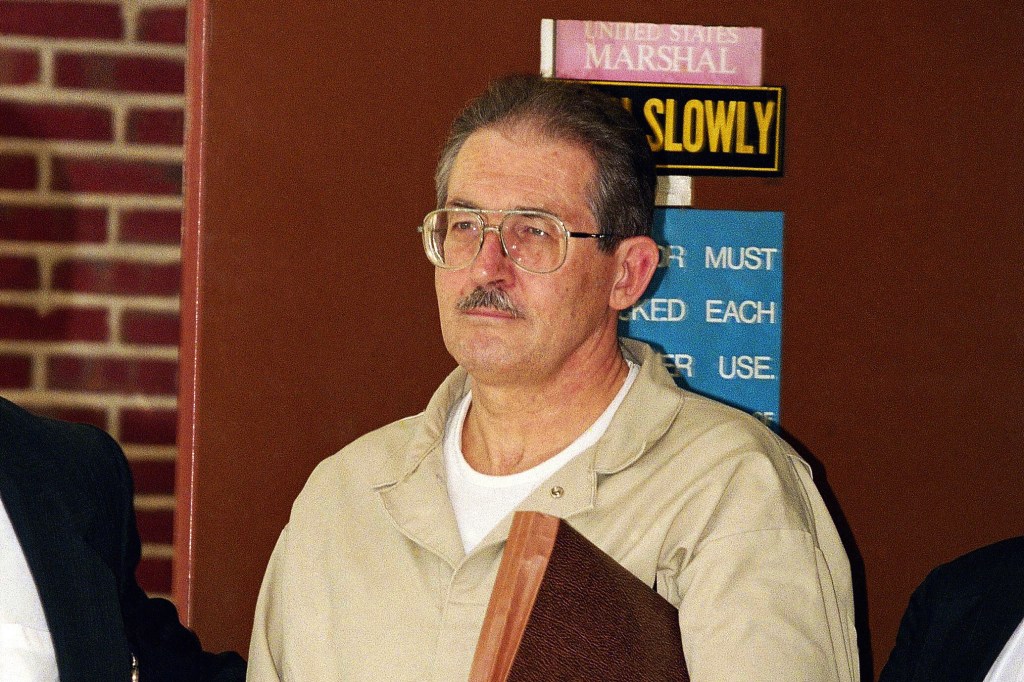

Former CIA agent Aldrich Ames leaves federal court after pleading guilty to espionage and tax evasion conspiracy charges April 28, 1994, in Alexandria, Va. AP

Former CIA agent Aldrich Ames leaves federal court after pleading guilty to espionage and tax evasion conspiracy charges April 28, 1994, in Alexandria, Va. AP

Prosecutors said Ames’ leaks caused the executions of Western agents working behind the Iron Curtain and deprived the United States of valuable intelligence material for years.

Unlike earlier double agents, most of whom turned their back on their country out of ideological sympathy with the Soviets or a misguided belief that Washington and Moscow were allies, Ames acknowledged he had worked with the Russians for money — in large part to fund the spendthrift lifestyle of himself and his second wife, Rosario, a former CIA informant.

“They [Intelligence assets] died because this warped, murdering traitor wanted a bigger house and a Jaguar,” said then-CIA Director James Woolsey, who resigned 10 months after Ames’ arrest amid questions about how he had gone undiscovered for so long.

In court, Ames professed “profound shame and guilt” for “this betrayal of trust, done for the basest motives.” But he downplayed the effect of what he had done, telling the court he did not believe he had “noticeably damaged” the United States or “noticeably aided” Moscow.

“These spy wars are a sideshow which have had no real impact on our significant security interests over the years,” he claimed, questioning the value that leaders of any country derived from vast networks of human spies around the globe.

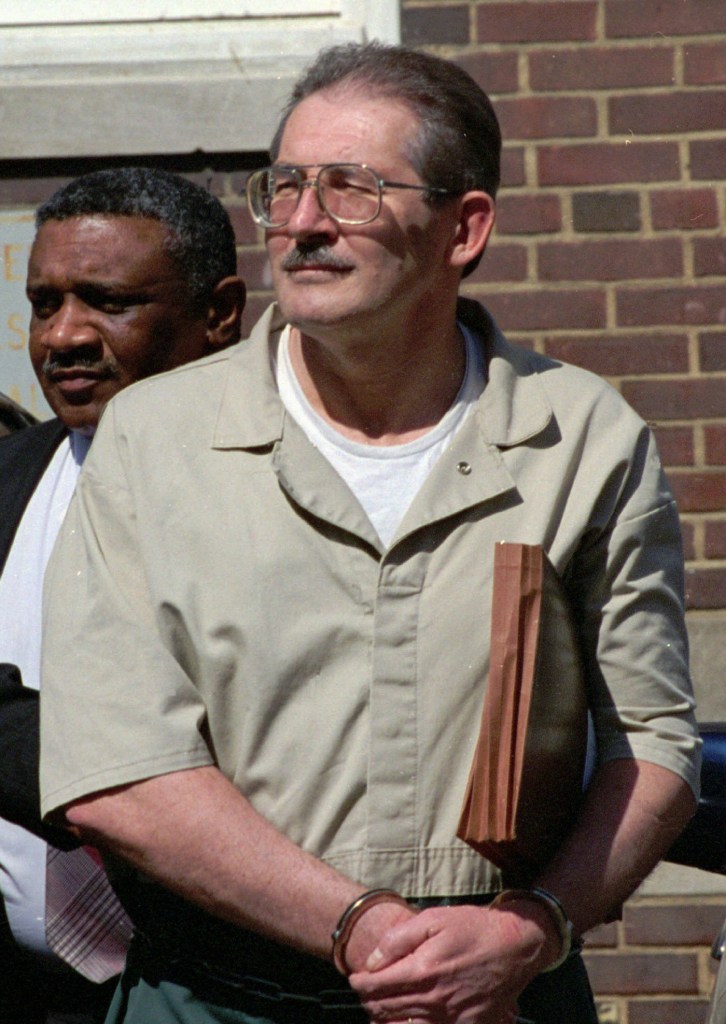

Former CIA agent Aldrich Ames leaves federal court April 28, 1994, in Alexandria, Va. AP

Former CIA agent Aldrich Ames leaves federal court April 28, 1994, in Alexandria, Va. AP

In a jailhouse interview with the New York Times following his sentencing, Ames said: “A number of people throughout the agency’s history have stolen money from the agency and have done terrible things for money. Very few have sold secrets to the KGB, and I think one of the reasons is because many of them would have found — there were a lot of barriers in the way. For me, by 1985, some of those barriers weren’t there any more.”

Ames was working in the Soviet/Eastern European division at the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Va., when he first approached the KGB, according to an FBI history of the case. He continued passing secrets to the Soviets while stationed in Rome for the CIA and after returning to Washington.

“I just passed what I had access to. And I had access to a wide range of stuff, but not to Soviet, sensitive Soviet operations,” Ames claimed to the Times. “Except little bits and pieces. But I had a wide range of other information that the KGB was eager to get, and happy to get … And so I passed a lot of that.”

Start your day with all you need to know

Morning Report delivers the latest news, videos, photos and more.

Thanks for signing up!

Meanwhile, the US intelligence community was frantically trying to figure out why so many agents were getting discovered by Moscow.

“You’ve got two or three or four thousand people running around doing espionage,” Ames told the Times from his jail cell. “You can’t monitor it. You can’t control it. You can’t check it.”

After Ames returned from Rome in 1989, his bosses received reports of his unusual wealth — namely, the new Jaguar and the fact that he had purchased the Arlington home for more than half a million dollars in cash, along with fine tailored suits and cosmetic dental work.

Despite the red flags, an internal investigation crawled along — in one instance, being stalled for months while the lone official on the case underwent a training course — until the FBI got involved in May 1993.

Woolsey himself admitted that “appropriate resources were not dedicated promptly in the Ames case” and partially blamed the agency’s culture, which he likened to “a fraternity … wherein once you are initiated, you’re considered a trusted member for life.”

Ames’s spying overlapped with that of FBI agent Robert Hanssen, who was caught in 2001 and charged with taking $1.4 million in cash and diamonds to sell secrets to Moscow. Hanssen died in prison in 2023 at the age of 79.

Rosario Ames pleaded guilty to lesser espionage charges of assisting her husband’s spying and was sentenced to 63 months in prison. Upon her release, she returned to her native Colombia with her son Paul, whom she shared with Ames.

With Post wires