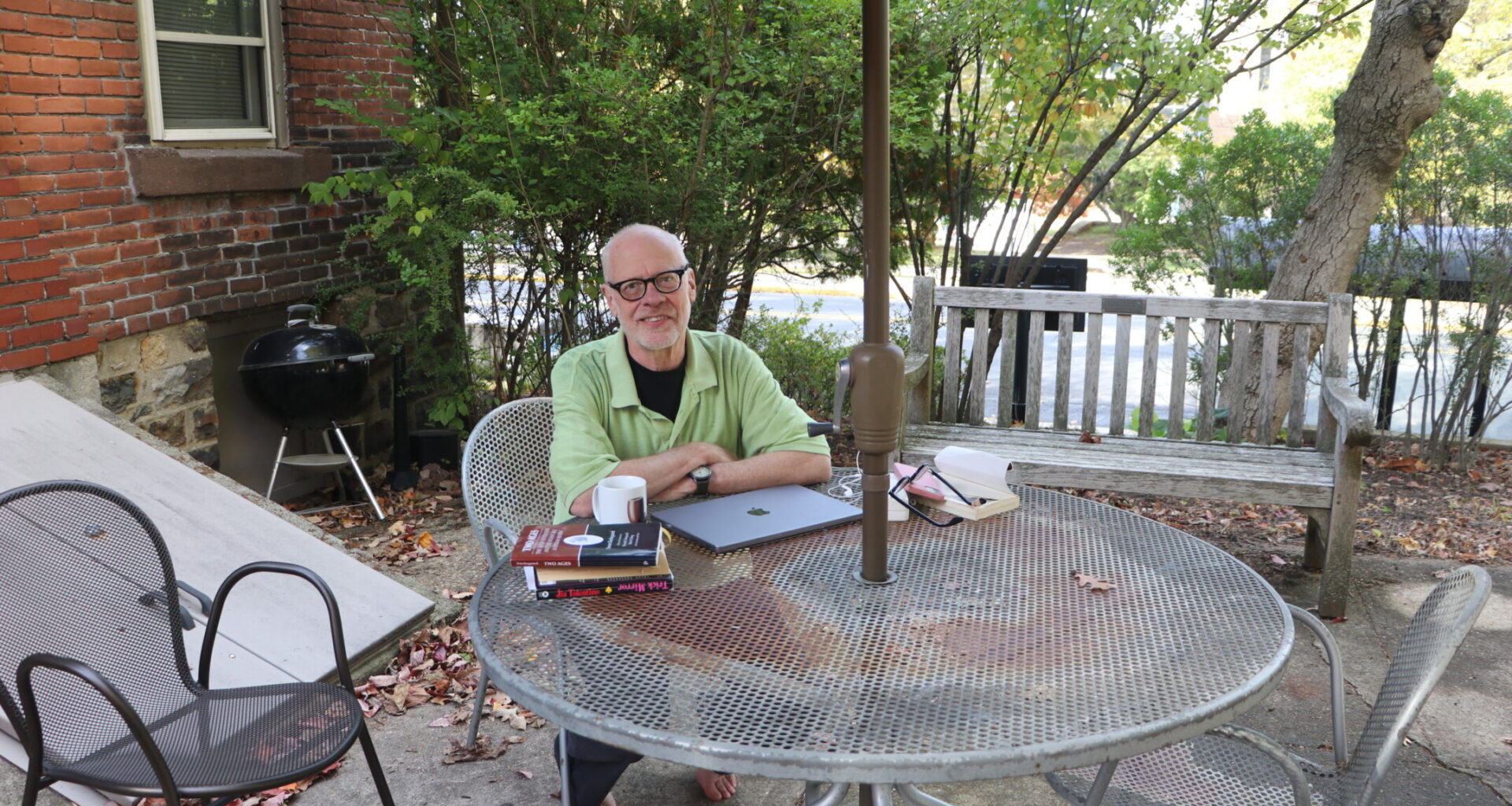

Inside his cottage-esque workspace, Gordon Bearn walks barefoot around tree stumps and branches. He keeps his office windows open to watch the leaves fall.

A cool, crisp breeze fills the air.

The tree stumps are from a maple tree cut down after a hurricane. Bearn collected and saved them as office decor inside the Lehigh University Philosophy Building.

“I like the outside,” Bearn said. “I think it’s sad when they take down trees.”

Gordon Clarence Frederic Bearn — his English father liked long names — has been teaching philosophy at Lehigh since 1986. He said now he’s even teaching the children of students he taught in the beginning of his career.

But with plans to retire in December, this semester will be his last at Lehigh.

Bearn has conducted philosophy research in topics such as esthetics and existentialism. His past projects explore philosophy as a way of life, from his 1997 book “Waking to Wonder: Wittgenstein’s Existential Investigations,” which examined Wittgenstein and Nietzsche, to his 2014 work “Life Drawing: A Deleuzean Aesthetics of Existence,” focused on creating a beautiful life.

Bearn grew up in Manhattan, attending boarding school in New England for high school before heading to Williams College, Oxford and Yale for graduate school.

He started his educational journey as a pre-med student, following in his physician father’s footsteps.

But along the way, he realized philosophy was the subject that encouraged rule-breaking. He liked rule-breaking.

“Boarding school taught me that rules were there to be broken, because what’s a teenager away from home going to do at an institution with a bunch of rules?” Bearn said. “It didn’t make me a rule follower, and philosophy is kind of like the same thing.”

In high school, Bearn worked in an immunology lab, which made him used to people talking about the meaning of their research, rather than simply memorizing facts.

He said it turned out well for him that philosophy was similar. Not only could he ask important questions like “What is justice” or “What makes a good life,” but he could also question his teachers on the first day and maybe even be right.

“Students are being hosed down with facts they don’t question,” Bearn said. “Socrates just wandered around town, found important people and asked them questions. He would find a general and say, ‘You’re a general, so what does courage mean?’ And it turned out no one ever thought about the concepts they used. Socrates would make them look foolish, and that was why I was first attracted to philosophy.”

He met philosophy at a time when he and his classmates weren’t so worried about employment. He recalled that students felt less financial pressure then, and the economy was better post-Vietnam war. People were hopeful.

Studying philosophy, particularly the notion of being able to challenge those around him and ask questions, has become integrated into Bearn’s character.

“I think it’s made me not a team player,” Bearn said. “I’m in here for myself. I’m not here to work on somebody else’s project. So I think it’s made me a bad disciple of the people I work with. I’m a follower for a while, and then I pull away.”

In his mind, philosophy and university principles clash with one another. From first-year to senior year, students are taught to work through problems more efficiently as they continue on.

Philosophy, however, has the same difficult questions in the beginning — like the nature of a good life and justice — as it does in the end. And Bearn said these are not problems that can be solved quickly.

“I’ve just recently begun thinking that we’re kind of like guerrillas in universities,” Bearn said. “Our job is to wonder what gets lost, when instead of thinking, we get answers from large language models. The university doesn’t really teach students to use thinking if it’s asking you to answer questions faster and faster.”

Bearn wants his classroom to be a safe-space to discuss taboo topics. He said in politically-fraught times, once the door of his classroom closes, students can ask questions they can’t ask their friends in their dorm rooms.

Dario Rivellini, ‘26, has taken one of Bearn’s existentialism courses. He said he would best describe his teaching style as priming students to educate themselves.

“He’s quite eccentric, so you never get a pretentious or stuffy feeling from him,” Rivellini said. “When you sit in a seat in his class, you don’t feel like there’s a professor there lecturing you, but rather an engaging discussion with friends around you.”

Bearn doesn’t believe exams are a true indicator of intellect because he says thinking can’t be examined. He said if one unplugs the urgency to come up with a solution, they won’t dread the act of thinking the way they may dread an upcoming exam. He wants his students to think.

“Thinking is more ungrounded than puzzles,” Bearn said. “Puzzles have solutions, but they are still fun because there is an aspect of play. With thinking, there is even more play because with puzzles, there are a bunch of rules like soccer. Playing without rules is what children do before they are taught the rule games.”

Bearn is increasingly pondering the idea of play after recently becoming a grandfather. He bought his grandson a toy, yet the child played with the box that housed the toy instead. This fascinated him.

He believes we should all lead our lives to try to find ways to “play” with everything around us, despite it being a direct paradox to the way items are designed with the purpose of efficiency and productivity.

“It’s like a platitude,” Bearn said. “You buy the fancy thing for the kid and they play with the box, because the fancy thing is designed by somebody with an advanced degree in what children like to do, but the box has almost more possibilities. You can go in it, hide behind it, rip it apart.”

Rivellini recalls one day Bearn walked into class, took off his shoes — which he never wears when teaching — and gave his students a branch he found on his commute to class.

They proceeded to pass around the branch and spent the first few minutes of class just looking at and discussing the branch. Now students collect sticks, branches and leaves that populate his philosophy hut.

To Bearn, these sticks and elements of nature are ways he can find play in everyday life.

“It’s part of feeling like everything is a toy,” Bearn said. “You don’t have to do anything special but be able to communicate with things. You may want to get away from something, but you need something else drawing you. I had a student once tell me the reason they like sticks so much is because they never yell at you for doing the wrong thing.”

Bearn also believes in magic. He said when he told his students this, they initially laughed at him. It wasn’t until he heard a track athlete in his class tell a story about his special socks that made his class realize he wasn’t crazy.

“I started believing in magic because I remember thinking, ‘Those people who say they feel better when the weather’s good — what’s up with them?’” Bearn said. “Now I realize that the weather is magic.”

Bearn’s ability to ponder abstract topics and find play in everyday life is not just an individual enigma, but one he tries to share with his students.

Abby Azar, ‘29, is also in one of Bearn’s philosophy classes. She said she likes that he is student-centric, and when a student speaks, he opens the discussion to the entire class.

“He told us a story about a family member being sick; he and his family were drinking gin and tonics, and his sick relative also wanted one but could only drink through a feeding tube,” Azar said. “So he told us that he had to shoot the gin and tonic through the feeding tube.”

After retiring in December, Bearn plans to move to Atlanta to live near his grandson.

He didn’t grow up with his grandparents nearby, but when his daughter and her wife asked him and his wife to move near them, it made him happy.

Bearn said his goal is to share a “wilder freedom” with students, feelings of play, beauty and thinking, which he says is what draws him to philosophy the most.