This article is the second in a series about Western Penitentiary’s history and impending demolition. Read the first installment here.

After serving as a global model for two decades, there was little room for Western State Penitentiary to do anything but decline. The system would crumble as the one thing holding it up came under fire.

According to Doug MacGregor, the author of “Western State Penitentiary/SCI Pittsburgh: A History,” local business owners had complained about prison labor since its inception, as a prison’s lack of labor costs allowed them to undercut their competition. Legislators often put them down, saying prison labor was crucial to the continued funding of prisons.

But, in true Pittsburgh fashion, steel brought new opportunities. Braddock’s Edgar Thomson Steel Works opened in 1875. Close behind came the rise of unions.

Once politicians began to see how massive a voting bloc unions created, they were eager to get a piece.

“What the unions wanted was ‘get rid of prison labor,’” MacGregor says.

In June 1897, Act 141 — “The Muehlbronner Act” — was signed into law. Created by Allegheny County Rep. Charles Muehlbronner, it eliminated the use of machinery for prison labor and limited the number of inmates who could work.

“From that point onward, prisons are no longer going to pay for themselves, and they’re going to be a massive burden,” MacGregor says.

While county building projects afforded work to some inmates, less than 10% were involved in labor by 1922, according to MacGregor’s book.

The loss of income limited funding for good food and building repairs. Simultaneously, prisoners were left locked in their cells with nothing to do.

“Over time, they give them less and less liberties, so it’s like you’re building a pressure bomb until something explodes,” MacGregor says.

Riots over the prison’s poor conditions literally flared up in 1921 and 1924; Western Pen’s interior was left in shambles and on fire after both events.

Some pressure was alleviated when Pennsylvania’s license plate factory moved to the site in 1925. But Western Pen was a shell of its former self.

To close or not to close

The ongoing chaos did not leave a positive impression on Pittsburghers and Pennsylvania leaders. Many wanted Western Pen gone.

In 1956, developers interested in what’s now the Marshall-Shadeland neighborhood wanted the penitentiary demolished — it was a blight to the locality. The prison remained open, but shortly after, the Department of Corrections tried to assuage similar concerns through rebranding.

Western Pen was renamed State Correctional Institution at Pittsburgh — colloquially known as SCI Pittsburgh — on Nov. 24, 1959. Terms like “warden” and “guard” were swapped for “superintendent” and “correctional officer,” MacGregor adds.

But the calls for closure wouldn’t cease.

“Keep out” signs posted at the northern entrance of Western State Penitentiary. The prison closed for the final time in June 2017. Photo by Roman Hladio.

“Keep out” signs posted at the northern entrance of Western State Penitentiary. The prison closed for the final time in June 2017. Photo by Roman Hladio.

In 1961, State Attorney General Anne Alpern called for the site’s abandonment following escape attempts at Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary. About a decade later, in 1973, then-Gov. Milton Shapp revived the debate, claiming that SCI Pittsburgh’s “ancient architecture” aided in prison escapes.

Both situations spurred investigations of the site, but they ended the same: State officials forwent demolition for site improvements or expansions. The latter attempt led to the construction of the so-called “A” and “B” blocks, which were essentially floors of cell pods with shared living spaces not dissimilar to some dormitory designs, MacGregor says. They were a major improvement over narrow stone cells.

While Pennsylvanians debated whether the prison should exist, inmates “were suing left and right,” MacGregor says.

The lawsuits served as an indictment of the conditions at SCI Pittsburgh, which worsened throughout the 1960s and 1970s. One suit from the 1970s won inmates the right to two hours of exercise a day — until then, they were receiving one hour or less.

In the 70-some years since the Muehlbronner Act, inmates had little to do aside from sit in their cells while the prison deteriorated around them.

Robert Faruq Wideman landed in Western Pen in 1976. He was sentenced to life after serving as an accomplice in a robbery-turned-murder the year prior, though he’s arguably better known for his part in the 1984 memoir “Brothers and Keepers,” by John Edgar Wideman — his brother — or the historic commutation of his sentence in 2019.

Wideman calls the prison during this period “wild.” Drugs and gambling were king, fights occurred often, and inmates often had the run of the place while guards opted to linger by desks.

“For about the first 10 years, I was pretty wild,” Wideman says. “We were trying to get out of there any way we could, and we were still wild into the drugs.”

Racism, he adds, ran the prison.

“There were guards that … just wanted to start trouble, just grab people up because they didn’t like them,” Wideman says. “They started more trouble than a lot of the inmates. Racism, hatred — we were prisoners, we were murderers and people that did robberies. So they didn’t like us, and, at that time, when we were young, we didn’t like them.”

During riots, inmates would throw furniture from the upper levels of Western Pen, smashing it on the first floor. This photo was taken after one such riot in 1953. Photo courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

During riots, inmates would throw furniture from the upper levels of Western Pen, smashing it on the first floor. This photo was taken after one such riot in 1953. Photo courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

With the prison already lacking funding, the ongoing lawsuits exacerbated its issues, MacGregor says.

“These prisons are doing whatever they can to cut corners,” MacGregor says. “They’re cutting food here, they’re cutting things there, and finally … there are many, many riots, escape attempts, several times where guards are attacked and killed, taken hostage.”

It wouldn’t be until after one such riot in 1987 that a lawsuit over the appalling state of the prison would be taken seriously.

“The judge forced a number of changes on the prison, which the prison just couldn’t comply with,” MacGregor says. “They tried as much as they could.”

Pre-mortem surge

Closure seemed imminent, yet SCI Pittsburgh would remain open for three more decades.

Its “saving grace,” so to speak, was something much darker than eleventh-hour state funding: Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, the United States entered an era of mass incarceration.

Following the Civil Rights Movement, politicians began to promote “law and order” messaging, according to the Vera Institute of Justice, and the national prison population would grow by about 400% between 1970 and 2000 due, in part, to harsher drug laws and longer sentencing.

Black Pittsburghers were already being arrested at a disproportionate rate throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. According to a 2018 Allegheny County Department of Human Services report, three times more Black people than white people were arrested for “less serious crimes” — like simple assault, vandalism, drug violations or drunkenness, among others — between 2001 and 2015.

That rose to five times more Black people than white people for more serious offenses.

From inside SCI Pittsburgh, the story was different.

“It was more racist in the ’70s,” Wideman says. “It didn’t go away in the ’80s, ’90s and 2000s, but it wasn’t as blatant as it was in the ’70s — just like in America. People began to look at each other in a different way after the Civil Rights Era.”

Robert Wideman having dinner at Tana’s Ethiopian Cuisine. Photo by Tony Norman.

Robert Wideman having dinner at Tana’s Ethiopian Cuisine. Photo by Tony Norman.

For example, Wideman recalls the so-called “Chow Hall” having two food lines, each with its own seating area. It wasn’t segregated, but throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, inmates instinctively separated themselves by race.

In any case, the surge of arrests led the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to build more correctional institutions in Mercer, Fayette and Greene counties.

Amid the growth, state leaders still deemed SCI Pittsburgh archaic. In 2005, word came that the prison’s oldest sections would be closed. Its newest blocks would temporarily be used for inmate intake and would eventually follow suit.

But in 2007 — two years later — they rescinded the plan.

“The inmate population just kept going crazy,” MacGregor says. “It started with just 70 guys in A and B blocks to, within three years, almost 2,000 guys again. We’re going to open up all the old blocks, so we’re running full tilt again.”

SCI Pittsburgh was meant to be open for only three to five more years. It persisted for 10.

The final superintendent

During that period, MacGregor worked alongside Superintendent Mark Capozza, who started in October 2012 and would go down as the last superintendent in SCI Pittsburgh history.

Even though the circumstances of the prison’s continued operations were dire, Capozza calls it the best prison he’s worked at in his 40-year career at correctional facilities.

“I miss the place,” he says.

After SCI Pittsburgh “closed” in 2005, inmates who had been serving life sentences there were sent to correctional institutions in Mercer, Greene or Fayette counties. When the Pittsburgh facility reopened, many of those so-called “lifers” were allowed to return so that they could be in a familiar place and closer to their families.

Once it was up and running, the Department of Corrections realized it could make further use of the site’s fully operational hospital facilities, which were equipped with units for chemotherapy, mental health crises and special needs and behavioral issues.

“So you had that core group of 40, 50 [life sentence] inmates that were the stabilizing force,” Capozza says. “Then you had your extreme behavioral challenges that were there, medical challenges, the mental health unit, and then you had the rest of the inmates, which was by far the bulk of our population [and they] were doing short sentences.”

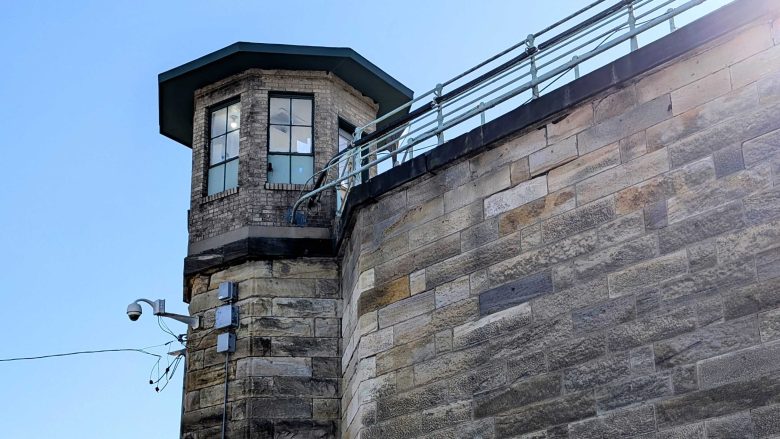

One light bulb remains visible in one of Western State Penitentiary’s northern towers. While the site had been used for filming earlier this year, no crews were present on Tuesday, Oct. 28 — the date the photo was taken. Photo by Roman Hladio.

One light bulb remains visible in one of Western State Penitentiary’s northern towers. While the site had been used for filming earlier this year, no crews were present on Tuesday, Oct. 28 — the date the photo was taken. Photo by Roman Hladio.

SCI Pittsburgh employees were also called upon to watch over inmates from rural correctional facilities who had been sent to Pittsburgh hospitals. Guards from an inmate’s respective prison would drive them to local medical facilities, where local officers would take over.

“There would be times where there were 10 inmates at outside hospitals, and we’d have two staff on every one of those inmates,” Capozza says.

Wideman, likewise, has positive memories of that stretch.

Capozza and his predecessor, Bill Stickman, “were people who didn’t just dislike inmates because they were inmates,” he says. “They treated you more like a person as long as you gave them that treatment back.”

On Jan. 26, 2017, Department of Corrections Commissioner John Wetzel announced the penitentiary’s closure, WHYY reports, praising the site’s potential for repurposing. To Capozza, SCI Pittsburgh’s 2017 closure was surprising, since its operations were unique compared to other local prisons.

The last inmate left on May 19, 2017, and soon after, the site was turned over to the Pennsylvania Department of General Services.

Since then, it’s sat vacant.