The phrase “linguistic justice” can take on several meanings, but at Pitt, it means meeting students where they’re at.

The Oxford Review defines linguistic justice as a set of principles that ensure people have equitable access to communication in the language they know best. Linguistic justice, according to TOR, involves recognizing language as an integral part of identity and culture, though practice varies on an individual basis.

Pitt programs, such as the Positive Racial Identity Development in Early Education, provide resources for how teachers can integrate linguistic justice into lessons. The linguistics department at Pitt also prioritizes research on sociolinguistics, which looks at the connection between language and identity.

Linguistic justice encompasses a variety of groups — including international students who do not speak English as a first language and may feel social and cultural barriers when it comes to classroom participation.

According to the most recent report by the Office of International Services, Pitt has over 3,000 enrolled international students. In classes like “ENGCMP 0200: Seminar in Composition,” students are exposed to academic writing practices and expectations. Classes like “ENGCMP 0152 ESL: Workshop in Composition” are designed specifically for international students.

Tina Cafasso, a part-time instructor in the English department, has taught Seminar in Composition for five years and takes an intentional approach towards including cultural differences.

“We have students coming from so many different countries, and we learn more from them,” Cafasso said. “I don’t want to change who they are. I just try to give them some ideas to make it a little bit stronger.”

Cafasso said she builds her classroom policies around inclusion and creating a community where students learn from each other, rather than fearing judgement.

“I know students from other countries are afraid to talk in class because they might not say [things] 100% correctly,” Cafasso said. “So I don’t [cold-call] on people a lot for that reason.”

Linguistic justice also includes English dialects often excluded from professional or academic settings, such as African American Vernacular English. While the use of AAVE has traditionally been excluded from academic spaces, the dialect has its own historical background, syntax and vocabulary.

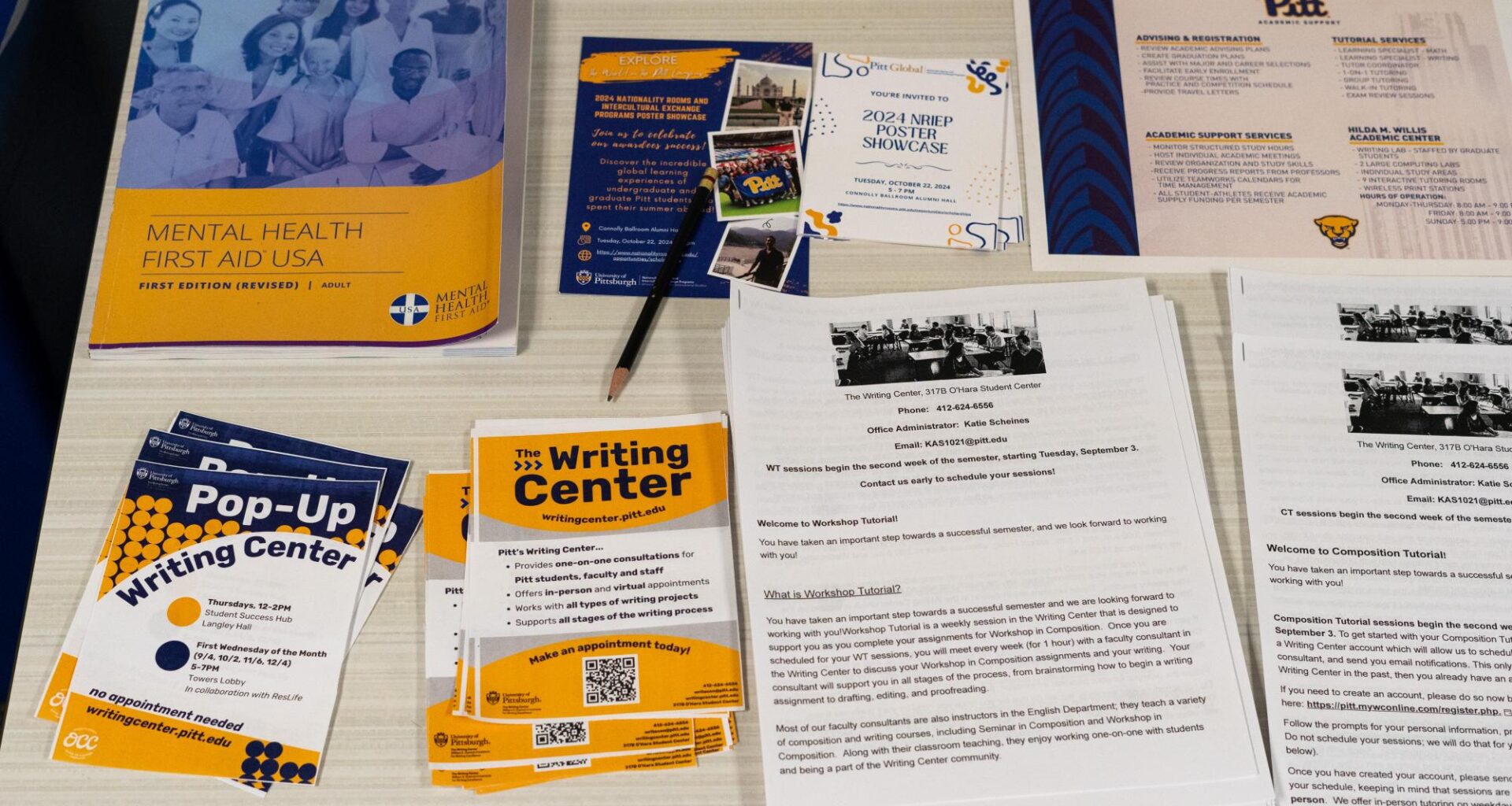

The Writing Center at Pitt prioritizes linguistic justice as one of its values, especially when thinking about traditional language standards. According to Angela Farkas, director of the Writing Center at Pitt, linguistic justice means “challenging language discrimination.”

“It means advocacy, it means allowing students to use their home language as a resource,” Farkas said. “It’s really important that we have conversations with students and try to get to know their linguistic backgrounds.”

Farkas noted how important language is to a student’s identity.

“None of us wants to be unintentionally perpetuating harms associated with discriminatory practices,” Farkas said. “It’s just important to let people know we believe language is identity, and it’s important not to erase identity or to make students hide their identities.”

Incoming international students are evaluated by the Test of English as a Foreign Language/Duolingo/International English Language Testing System Institute for English language placement. The Writing Center has consultants for international students learning English as a second language who might be adjusting to American educational expectations.

“We all, as a group, are respectful of differences and don’t automatically assume, for example, if we see an accent in writing, that’s an error,” Farkas said. “We don’t automatically see different varieties of English or accented English as an error or a problem unless it interferes with meaning with a particular context.”

According to Farkas, representation is a core part of linguistic justice at Pitt.

“We want to make it possible to have many voices in the University,” Farkas said.

Aizha Castellano, a junior teacher education major and peer tutor in the Writing Center, spoke about her experience with linguistic justice in the “ENGCMP 1210: Tutoring Peer Writers” course — a prerequisite for the peer tutor internship with the Writing Center.

“We explore what [linguistic justice] is and why it’s necessary to acknowledge social privilege, structures of power and linguistic validity,” Castellano said.

Farkas said students are essential when looking towards a more inclusive linguistic future.

“[The peer tutors are] usually in the forefront of pushing for more actions and advocacy from us for linguistic justice,” Farkas said.

Castellano encourages Pitt educators and programs to take a deeper look into practices of social justice in writing. Castellano said initial training “shouldn’t be the end of the conversation.”

“Being aware of an injustice doesn’t suddenly push people into action,” Castellano said. “There needs to be more intentionality to the approach, and [it has to be] made a daily part of our lives, just as linguistic injustice is a daily lived experience for people.”

Cafasso believes effective communication and taking the time to learn from peers is essential in pursuing linguistic justice in the classroom.

“Everyone’s welcome to the table. Your opinion matters,” Cafasso said. “And who’s to say just because someone’s lived here forever and knows the English we expect that their answer is 100% correct?”