The main characters in Ken Burns’ “The American Revolution” aren’t exactly strangers. The new PBS docuseries, which premiered Sunday, spends ample time with George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and so many other stars of U.S. history textbooks. But to tell the complete story of our nation’s unlikely independence, Burns brings in more voices.

“The American Revolution” incorporates nearly 200 historical figures, many oft forgotten in retellings of the rebellion and subsequent war with Great Britain. Several lived or worked in Philadelphia and southern New Jersey. They include a printer, a poet, a reverend and a boy who’d grow up to be a freedom fighter. As Burns’ documentary airs its next pieces through Friday, listen for their words:

MORE: James Garfield, the focus of a new Netflix show, didn’t want to be president. But a Philly man’s ploy put him on the ballotJames Parker

Benjamin Franklin‘s friend and business associate James Parker died before America won its independence, but he was there for the rebellious early rumblings. Born in Woodbridge, New Jersey, he was a prominent printer who established the first printing house in the state. He also spent part of his career in Philadelphia working for Franklin. Before his death in Gloucester in 1770, he helped established colonial periodicals like the Connecticut Gazette. The Constitutional Courant was also printed on his press in Woodbridge. This broadside railed against the 1765 Stamp Act, and included a reprint of Franklin’s famous “Join or Die” cartoon.

Numerous letters between Parker and Franklin survive, including one featured in Burns’ documentary in which Parker chronicles the brewing dissent.

“A black Cloud seems to hang over us; but whether it will blow past, or the Thunder break in upon us all, is what he alone, who guides it, can tell,” he wrote. “But poor America is like to bleed, if the Storm blows not over: Nay, it appears to me, that there will be an End to all Government here, if it does not.”

Hannah Griffitts

Quaker poet Hannah Griffitts rallied colonial women to the cause with her stirring words, which critiqued British rule. She advocated for the boycott of taxed goods in her 1768 poem “The Female Patriots,” which is read in part in the PBS series. It specifically calls out George Grenville, then the prime minister of England.

“Let the Daughters of Liberty nobly arise, and tho’ we’ve no voice, but a negative here,” the poem reads. “…Stand firmly resolved & bid Grenville to see that rather than freedom, we’ll part with our tea.”

Griffitts, the daughter of former Philadelphia mayor Thomas Griffitts, continued writing as war broke out. She also penned verse about the 1793 yellow fever epidemic and odes to deceased family and friends throughout her lengthy life. She died in 1817 at the age of 91.

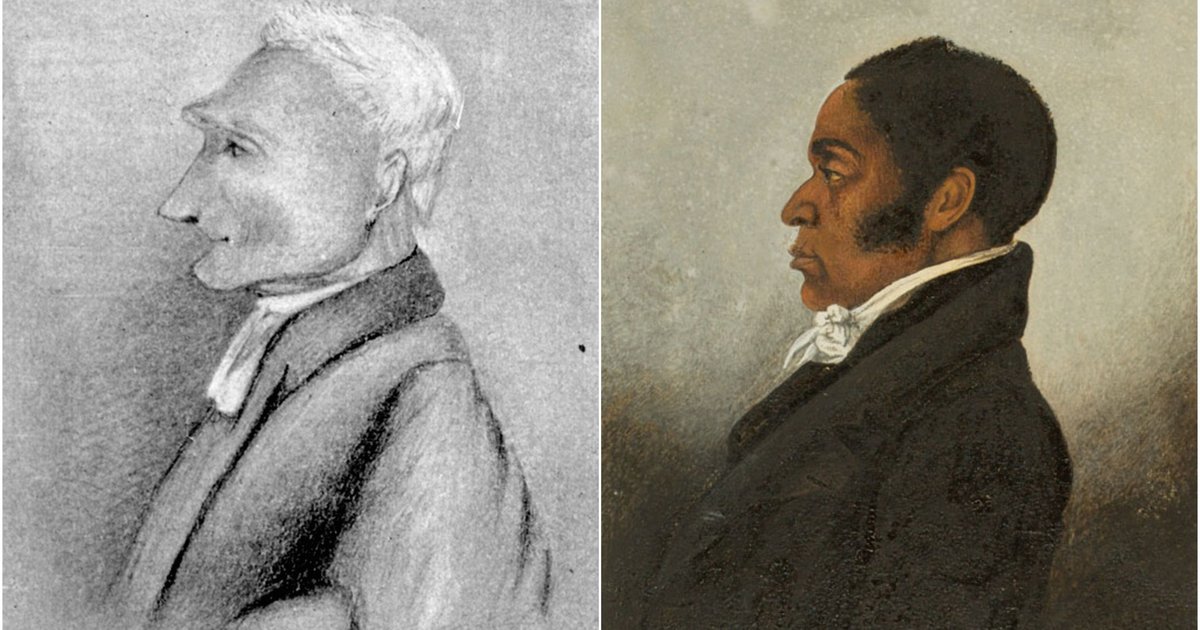

Nicholas Collin

The revolution placed Reverend Nicholas Collin in an awkward position. His congregation in Swedesboro, New Jersey, was politically divided and he, as a Swedish citizen, refused to pledge loyalty to another country. So he attempted to stay out of the conflict, with limited success.

In 1777, the New Jersey militia took Collin prisoner. A friendly doctor advocated for his release, according to the reverend’s diary, but the troops still expected Collin to swear allegiance. He negotiated an amended oath, and returned to his church.

Though he rode out the rest of the war unscathed, Collin occupied an uneasy position. Historian Richard Waldron argues he was likely seen as an English sympathizer, a suspicion only stoked when he prayed over wounded Hessian, not American, soldiers at Fort Mercer. He later served churches in Philadelphia, including the Gloria Dei Old Swedes Episcopal Church. Collin was the last Swedish minister at that house of worship.

James Forten

When American rebels read the Declaration of Independence aloud in the streets of Philadelphia, a young James Forten was listening. He was only a child then, but he’d grow up to be a patriot in his own right.

As a Black man, Forten’s love of country was complicated. He spent most of his life preaching abolition and fighting a movement to send free Black people like himself to Africa. Even still, he was proudly American. When he was taken prisoner by the British as a powder boy aboard the Royal Louis, he chose imprisonment aboard a “floating jail” rather than renounce his country for safe passage to England.

Upon his release from the prison ship, he returned to Philadelphia and started a family of activists. His wife and daughters founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, which lobbied politicians and helped enslaved people to freedom. One of those daughters, Harriet, married the influential abolitionist Robert Purvis; their home became a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.