By Jack Tomczuk

Philadelphia is moving closer to having to cut ties with a Chester incinerator that currently burns about 30% of the city’s trash.

City Council advanced a proposed law Monday that would prohibit Mayor Cherelle Parker’s administration from hiring companies to incinerate waste. The legislation is nearing a final vote as the city prepares to negotiate new deals with contractors to dispose municipal trash.

“Right now is our chance to chart a healthier, cleaner and greener path,” Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, the bill’s author, said during a hearing.

Lawmakers voted the bill out of committee, defying a request from the Parker administration to delay a preliminary decision.

Current trash contracts and costs

Under the current contract, City Hall pays WM, previously known as Waste Management, and Reworld, formerly Covanta, more than $50 million a year to haul garbage from transfer stations after trash compactors pick it up curbside.

WM dumps around 70% of the trash at a pair of Bucks County landfills, while Reworld takes the rest to the Delaware Valley Resource Recovery Facility, the company’s incinerator in Chester that burns waste for energy, city officials testified.

A 2018 contract with both firms expires in June, at the conclusion of the fiscal year. The city generally signs 4-year deals with three additional single-year options, according to representatives from the Parker administration.

Eliminating incineration could result in a 12% cost increase, equivalent to about $6.5 million annually, as regional landfills begin hitting capacity, said Philadelphia Sanitation Commissioner Crystal Jacobs Shipman.

Shipman and Carlton Williams, Parker’s clean and green director, asked Council to hold the legislation in committee until companies submit applications for the waste contract. The city is planning to conduct its own analysis of disposal methods as part of that process, Williams added.

He noted that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s hierarchy of waste considers waste-to-energy facilities, such as the Chester plant, more sustainable than landfills, though that finding is under review.

“The administration applauds the bill’s efforts to improve air quality and environmental justice concerns for the residents of Chester,” Williams said. “However, there is a need for more objective data to support the claims of this bill in its entirety.”

He expressed hope that the city would receive proposals for more innovative solutions, such as an anaerobic digestion system, which breaks down natural waste to convert it into biogas, fertilizer and other products.

“We don’t need another study to tell us what we already know to be true, to give the city an excuse to kick the can down the road for another seven years,” Gauthier remarked earlier in the hearing.

“Our community is sick”

The Reworld facility, which opened nearly 35 years ago, is the largest incinerator in the nation, Delaware County officials testified. It processes 1.2 million tons of trash a year and produces enough energy to power 51,000 homes, according to the company.

About a third of the trash burned there is shipped from Philadelphia, with the remainder primarily coming from Delaware County and New York City.

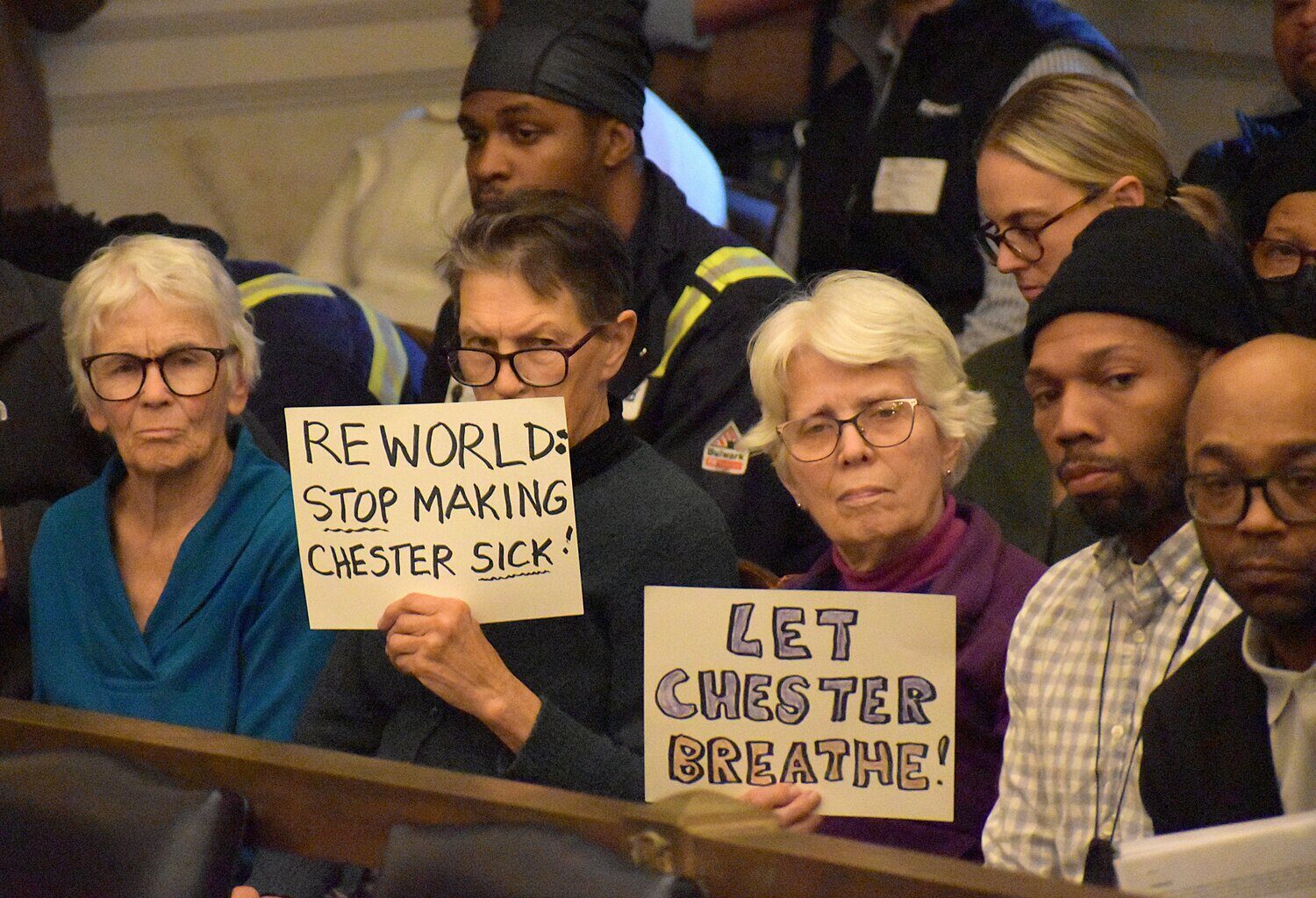

Proponents of the ban cite the plant as a textbook example of environmental racism. Chester’s population of about 33,000 is 71% Black; more than 30% of residents fall under the federal poverty line, and they have a high rate of asthma and other health problems.

“Basically, our community is sick,” said Zulene Mayfield, founder of Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, a group that has advocated against the incinerator. “Our children have asthma, and we are burying members of our community, burying them every day.”

“When Philly went through the trash strike, one side of me, I felt very sad. But the dark side of me was like, Now they can see the crap that they send to my city every single day.”

Kim Bradford, Reworld’s Pennsylvania environmental manager, told lawmakers that the incinerator is a small contributor to overall air quality in Delaware County, where Chester is located.

A 2-page report commissioned by the company and published last month found that the plant’s pollutants fell below federal thresholds and do not “pose unacceptable health risks” to Chester residents. The analysis was based on modeling conducted with real-world emissions data.

Chester Health Commissioner Kristin Ball Motley referred to the report as “a disgrace,” telling legislators that it is an “insult to your intelligence.” That feeling was shared by Councilmember Nina Ahmad, who said, “To me, these numbers mean nothing.” She believes Reworld should complete a study incorporating the actual health outcomes of its neighbors in Chester.

Support for the ban

Elected officials from Delaware County and the City of Chester encourage passage of the incineration ban.

A study conducted on behalf of the county found that sending garbage to the waste-to-energy plant is 2.3 times more harmful than trucking it directly to a landfill, and far worse for localized health impacts.

Delaware County leaders adopted a zero-waste plan in September that commits to weaning off the Reworld incinerator. However, the five-year strategy is reliant on several multimillion-dollar projects to revamp transfer stations and expand a landfill. Its contract with Reworld expires at the end of 2027.

Though Chester receives $5 million a year from the company as part of a benefits agreement, the city’s mayor, Stefan Roots, told Council he would like to see the plant closed and have the waterfront site redeveloped, possibly as part of an expansion of the nearby Philadelphia Union soccer complex.

Council President Kenyatta Johnson did not participate in the preliminary vote, but he was spotted clapping in the body’s meeting room as a motion was made to move the bill out of committee.

Mike Driscoll, of the 6th Council district, was the only member to express opposition during the voice tally. A final vote could be held as soon as Dec. 4.