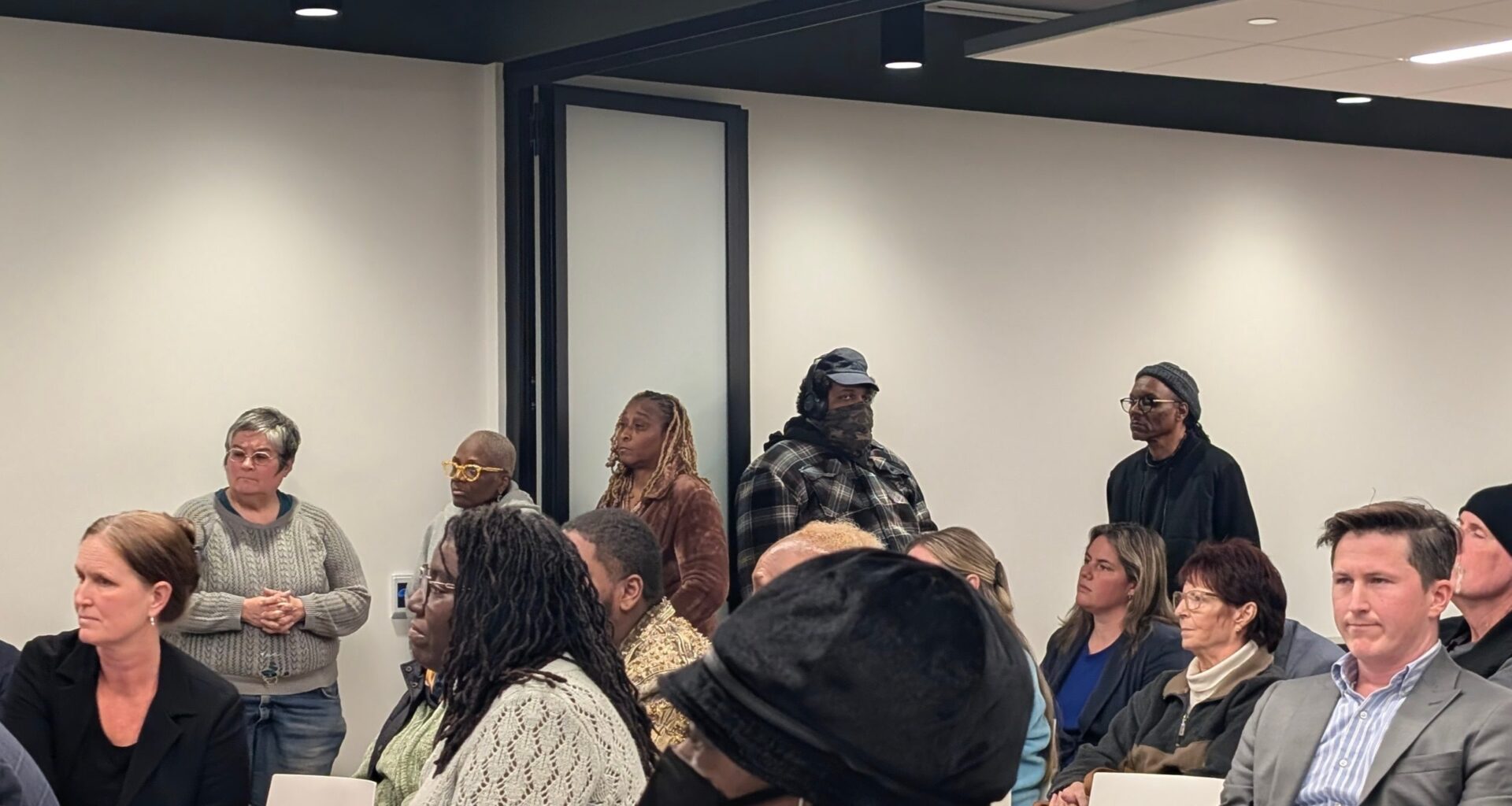

Hazelwood residents painted a dire picture of their neighborhood at the Pittsburgh Planning Commission meeting on Tuesday, Nov. 18.

Residents and their City Council representative, Barb Warwick, say refuse escapes from a recycling facility into the streets, delivery trucks idle outside of homes for hours, salt domes create fine white powder that gets trapped in blankets and couch cushions and a train depot’s overhead lights turn nighttime to day.

“We cannot have our windows open between the noise and the fumes from the trucks,” said Hazelwood resident Theresa Nagy. “It feels like living at a truck stop.”

Since August, Warwick has been seeking to rezone a stretch of Hazelwood’s riverfront area from General Industrial to Industrial Mixed-Use after recycling collection company Republic Services sought to become a garbage transfer station, where waste would be deposited and wait to be transferred to a landfill at a later date.

Warwick said it’s hard to make up for the past environmental injustices put upon lower-income and Black communities in Pittsburgh, but it is possible to keep it from getting worse.

“Just the idea that something that harmful would come to this community that has already been so incredibly harmed by all the industry happening right next to it, you ask yourself, ‘What can we do?’” she told NEXTpittsburgh ahead of the meeting.

Part of the city’s tool kit in scenarios like this, she said, is zoning.

A map of Hazelwood’s zoning district. The dark blue portion, outlined in lighter blue, is the stretch of land that City Councilmember Barb Warwick seeks to rezone. Image courtesy of Barb Warwick.

A map of Hazelwood’s zoning district. The dark blue portion, outlined in lighter blue, is the stretch of land that City Councilmember Barb Warwick seeks to rezone. Image courtesy of Barb Warwick.

According to city documents, Riverfront General Industrial zoning is meant for “heavier industrial uses that may produce external impacts such as smoke, noise, glare or vibration.” Riverfront Industrial Mixed-Use diversifies this to include “light industrial, commercial and high density residential development.”

Hazelwood’s pitch for rezoning previously went to Hearing and Action on Tuesday, Oct. 7, but was tabled until the Nov. 18 meeting after Republic Services representatives and lawyers, alongside lawyers representing Allegheny Valley Railroad and CSX pushed back. They claimed they didn’t have proper notice of the changes and that the changes are an attempt to “zone out” the railroad and existing businesses.

Since then, the idea that rezoning would affect railroads has been put to rest, as federal preemptions — essentially, a railroad company’s ability to supersede specific local laws — allow their continuance. But at the Nov. 18 meeting, railroad attorneys again argued that rezoning was an effort to remove them from the property.

Lights above a Duquesne Light Co. station seen from a home on Langhorn Street. Photo courtesy of Barb Warwick.

Lights above a Duquesne Light Co. station seen from a home on Langhorn Street. Photo courtesy of Barb Warwick.

“We have a difficult time, on the one hand, hearing, ‘Well, there’s railroad preemption. We can’t do anything,’ and then this process continues and continues, and statements are made of, ‘Wish we could get rid of the uses that are there,’” said Brendan O’Donnell, an attorney representing Allegheny Valley Railroad.

O’Donnell’s comment referenced a statement made by Warwick earlier in the evening.

“Look, if I could change the operations that are down there now, trust me, I would,” she said. “If I could get rid of some of the facilities that are down there now that are harming residents of those communities, I would. But, unfortunately, I can’t. We cannot zone existing operations out of where they are. All we can do is make zoning changes that will impact where we can go.”

Republic Services also made the case that it was the previous owners of the waste collection facility that had allowed garbage to spread throughout the neighborhood. Republic Services has been the property owner since February.

Mark Duncan, the site’s operations manager and a Penn Hills resident, has worked at the site for 10 years under three different administrators. He said trash used to touch the property’s fence line, but is now all kept inside its central warehouse.

“I’m here to tell you that it has changed; there is a difference,” Duncan said. “That smell — I’m going back there when I leave here. You want to come? You won’t be able to smell nothing.”

But Hazelwood residents didn’t agree with Duncan’s view.

“I can’t sit on my porch without the fumes from the trash,” said Denise Johnson, who lives on nearby Gertrude Street. “Maybe he’s immune to it because he works there, and you can’t smell it, but I say come move to our neighborhood and you’ll be able to smell it.”

Republic Services waste storage warehouse and nearby Hazelwood homes. Photo courtesy of Barb Warwick.

Republic Services waste storage warehouse and nearby Hazelwood homes. Photo courtesy of Barb Warwick.

As the meeting came to a close, commissioners seemed hesitant to put it up for a vote. Even before the presentation had begun or testimony was accepted, they toyed with the idea of taking an extension to confer with city lawyers.

Many commissioners agreed that they’d rather see a continued dialogue between Republic Services, railroad companies and City District 5 residents rather than an immediate zoning change, as most of the concerns raised — light and sound pollution, excessive smells and the presence of rodents at the nearby facilities — do not stand to be addressed by a zoning change.

Assuming no legal action is raised, existing properties are allowed to remain as non-conforming structures in the new zoning district and will continue to operate as usual. New uses — like a waste transfer station — could not be added, though.

After deliberation, commission Vice Chairwoman Rachel O’Neill put the question to Warwick: “Do you want us to go to a vote today, or do you want some time to negotiate some sort of agreement like that?” O’Neill asked.

Warwick replied that she’d prefer a vote.

O’Neill, alongside Commissioners Jean Holland Dick, Dina Blackwell and Phillip Wu voted in the proposal’s favor, while Chairwoman LaShawn Burton-Faulk and Steve Mazza dissented. Commissioners Mel Ngami, Pedro Quintanilla and Monica Ruiz were not present for the vote.

With Planning Commission approval, the effort now heads to City Council and will face a public hearing process, though no dates for either are set.