Pittsburgh is a city of firsts: movie theaters (nickelodeons), AC electricity, commercial radio broadcasts, gas stations, the polio vaccine and … showboats. All but the latter persist into the 21st century.

Showboats became one of the nation’s most popular entertainment industries, but they are among Pittsburgh’s least recognized contributions to American history. Pittsburgh’s showboats and people were fertile sources for novelist Edna Ferber, whose 1926 book “Showboat” became a runaway hit in print, on Broadway and in movie theaters.

One 20th century showboat trailblazer, Ralph Emerson Gaches, was born here. The Reynolds family was a three-generation showboat dynasty based in a harbor near the Glenwood Bridge. Their histories, and others, flow downstream from the early 1800s and are upstream from Pittsburgh’s current river entertainment economies that include the Gateway Clipper fleet and Rivers Casino.

“A showboat would be like a barge, a theater barge,” says Donald Sanders, a retired riverboat captain and author of the 2023 book “The River: River Rat to Steamboatman.” Sanders, a Northern Kentucky native who now lives along the Ohio River in Indiana, went to work on the rivers in the 1950s. “It’d be like a theater built on a barge … you go inside and there would be the stage and there would be auditorium.”

Showboats offered people in big cities, small towns and farming communities live theater, music and comedy acts in an era before radio, television and the internet. They featured scripted plays with actors and custom-built sets, vaudeville and band and orchestra performances. Some were even made into floating movie theaters.

The Island Queen was one of many steamboats that traveled between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Based in Cincinnati, the excursion boat exploded in the Monongahela River in 1947. Courtesy of the Heinz History Center Detre Library and Archives.

The Island Queen was one of many steamboats that traveled between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati. Based in Cincinnati, the excursion boat exploded in the Monongahela River in 1947. Courtesy of the Heinz History Center Detre Library and Archives.

Sanders once captained the Delta Queen, now a National Historic Landmark permanently moored in Louisiana. Built in 1927, it is one of the nation’s last excursion steamboats. Pittsburgh was the end of the line for the Delta Queen’s runs, which began service to the Steel City in 1946 and last visited in 2008.

Sanders has many memories of Pittsburgh. One of the most enduring is the time he was part of the steamboat Avalon’s crew. They arrived during the 1960 World Series and experienced the Bucs defeating the New York Yankees as the raucous celebrations spilled out from Forbes Field and across the city.

But the Delta Queen, the Gateway Clipper fleet and the cruise ships that now make their way to Pittsburgh are very different types of boats from their showboat kin. Showboats relied on towboats to move them from landing to landing, and today’s excursion boats, except for a few historic survivors, are not steam powered. People on shore aren’t treated to regular carillon music.

“A showboat is non-propelled,” says Sanders. They usually have to have an assist, like a towboat, something to push it.” The earliest showboats simply drifted downriver.

Showboats and Pittsburgh

In 1831, William Chapman’s Floating Theater cast off from Pittsburgh and floated down the Ohio River. The Floating Theater was the first purpose-built showboat. By the turn of the 20th century, Pittsburgh boatyards and river men had built dozens of showboats. Harbors along the Monongahela and Ohio rivers became destinations and home bases for them.

Though there were many small boatyards in Pittsburgh’s history, two local companies stood out for the number of boats produced and the distinguished careers they had: the Dravo Corp.’s shipyards on Neville Island and the John Eichleay Jr. Co.’s Hays boatyard.

The Manitou, left, docked at the John Eichleay Jr. Hays boatyard in the late 1920s. Courtesy the Murphy Library Special Collections/ARC, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

The Manitou, left, docked at the John Eichleay Jr. Hays boatyard in the late 1920s. Courtesy the Murphy Library Special Collections/ARC, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Some showboat owners built their own — Capt. Thomas Reynolds was one of them. Born in West Virginia in 1888, he grew up on a shantyboat and began his floating entertainment business with a floating movie theater.

Boatyard near the Glenwood Bridge, undated photo. Photo Courtesy of Rivers of Steel.

Boatyard near the Glenwood Bridge, undated photo. Photo Courtesy of Rivers of Steel.

Based in Point Pleasant, W. Va., Reynolds and his extended family wintered in Pittsburgh. Their local harbor was an old coal landing that belonged to the Clyde Coal Co. The landing was downstream from the Glenwood Bridge on the north bank of the Monongahela River, where Reynolds began building the showboat Majestic in 1922.

Capt.Thomas Reynolds built the Showboat Majestic in Pittsburgh in 1922. After a long career working the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, the boat was retired in Cincinnati where it became a university-owned theater. Courtesy the Murphy Library Special Collections/ARC, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Capt.Thomas Reynolds built the Showboat Majestic in Pittsburgh in 1922. After a long career working the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, the boat was retired in Cincinnati where it became a university-owned theater. Courtesy the Murphy Library Special Collections/ARC, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

The first Reynolds showboat, the Illinois, sank after burning in 1916. Reynolds replaced it with two showboats, the America and the Superior. Construction began on the Majestic in 1922. Three generations of Reynolds family pitched in or watched its construction.

Catherine Reynolds King, who chronicled her family’s history, was born in 1918. “Although I was only 4 years old that winter, I have vivid recollections of sitting by our living room and kitchen windows aboard the America watching as they built the new showboat,” King wrote in her 1992 memoir, “Cargo of Memories.”

While her family lived in Pittsburgh, King attended school in Glenwood. “I learned to perform a variety of acrobatic stunts in gym class at the Township Peebles School,” King wrote.

Showboats were a family business. The Reynolds family was one of many with boats built in Pittsburgh and who regularly plied the three rivers entertaining people. King was one of several Reynolds children who worked on the boat and who performed in its shows until 1956; Reynolds sold the boat in 1959.

Barnum of the Rivers

Ralph and Beatrice Gaches didn’t have any children, but they became a showboat power couple.

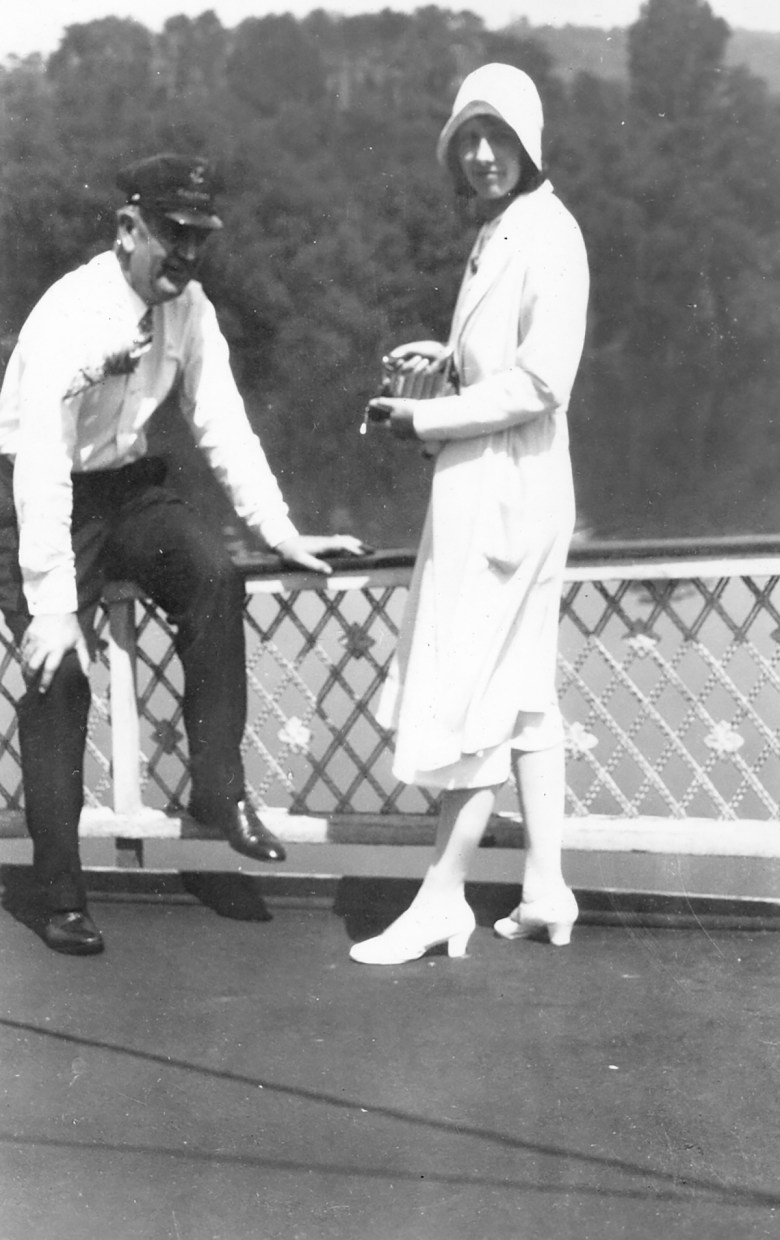

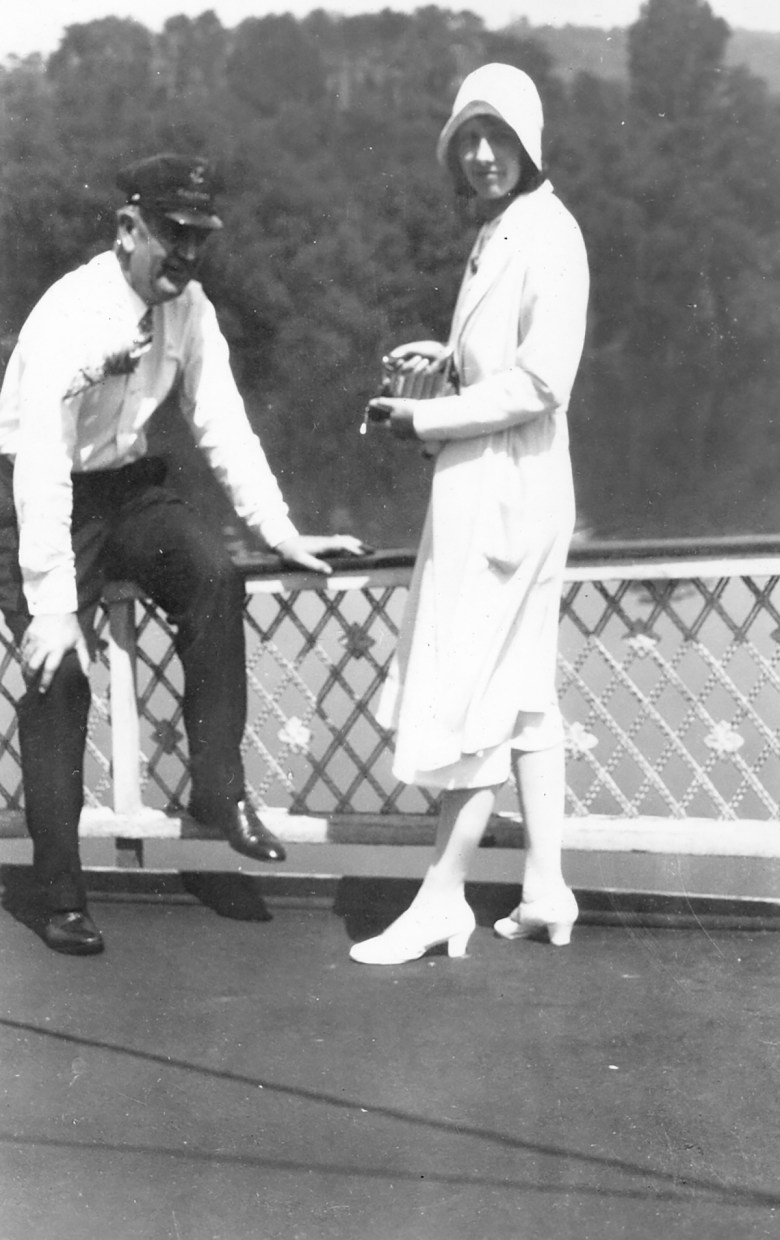

Ralph and Beatrice Gaches in an undated photo. Photo courtesy the Cincinnati Public Library.

Ralph and Beatrice Gaches in an undated photo. Photo courtesy the Cincinnati Public Library.

Ralph Emerson Gaches — later in life he called himself Ralph Waldo Emerson — was born in Pittsburgh in 1873. “He dropped his surname because he insisted no one could pronounce it and because Emerson was a distinguished name,” wrote showboat owner Billy Bryant in a 1936 memoir, “Children of Ol’ Man River.”

The son of a popular railroad conductor who had moved the family from Pittsburgh to West Virginia, Ralph Gaches ran away from home as a teenager. He signed on with a riverboat in the mid-1890s and quickly worked his way up to pilot and captain.

While managing Capt. Billy Price’s showboat, the Water Queen, Ralph Gaches bought his first showboat. Later historians hailed Gaches’ Grand Floating Palace as a premier showboat. “Its name became synonymous with the best in the entertainment world,” wrote historian Carl Bogardus in a 1979 Kentucky newspaper feature on Ohio River showboats.

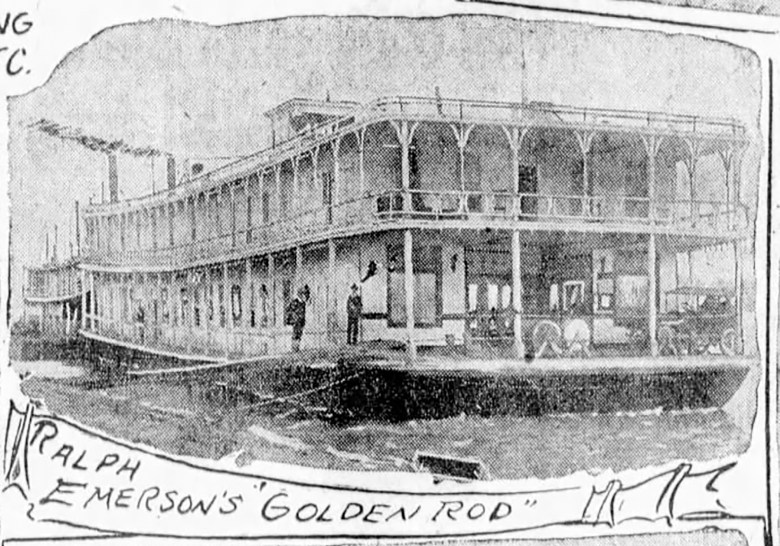

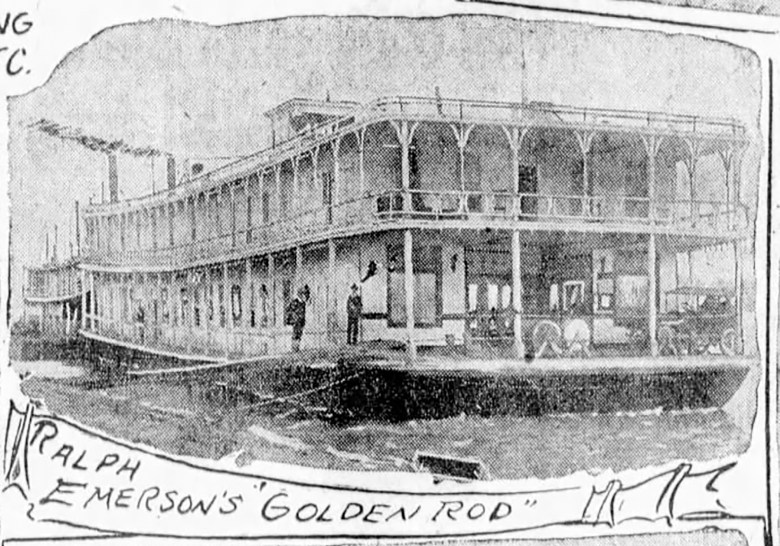

Ralph Gaches went on to own as many as nine showboats (and their tow boats), including some of the biggest names in floating entertainment, including the Goldenrod, the Cotton Blossom and the Manitou.

The Manitou showboat in an undated photo. Public domain.

The Manitou showboat in an undated photo. Public domain.

Dubbed the Barnum of the Rivers by his contemporaries, Ralph Gaches worked the Mississippi and Ohio rivers between the 1890s and 1930. As a promoter, he set the standard for all who followed in his wake.

“Each of the big-boat operators has left the distinct impress of his personality and his achievement as an inheritance to the rivers,” showboat historian Philip Graham wrote in 1951. “There was one man among these big-time operators who seemed to have the qualities of them all … he was Ralph W. Emerson. His name weaves itself in and out of almost every important showboat of the era.”

Photo of the Goldenrod published in the Evansville Courier, June 13, 1920. Via Newspapers.com.

Photo of the Goldenrod published in the Evansville Courier, June 13, 1920. Via Newspapers.com.

Key among Ralph Gaches’ contributions to showboat history were his skills as a huckster. “Ralph Emerson was a good advertising man,” wrote Graham. While managing the Water Queen, Gaches changed the ways showboats advertised their arrival. Gaches went ashore miles ahead of the next stop and used bicycles and cars to go to the next landing where he plastered show bills around the towns.

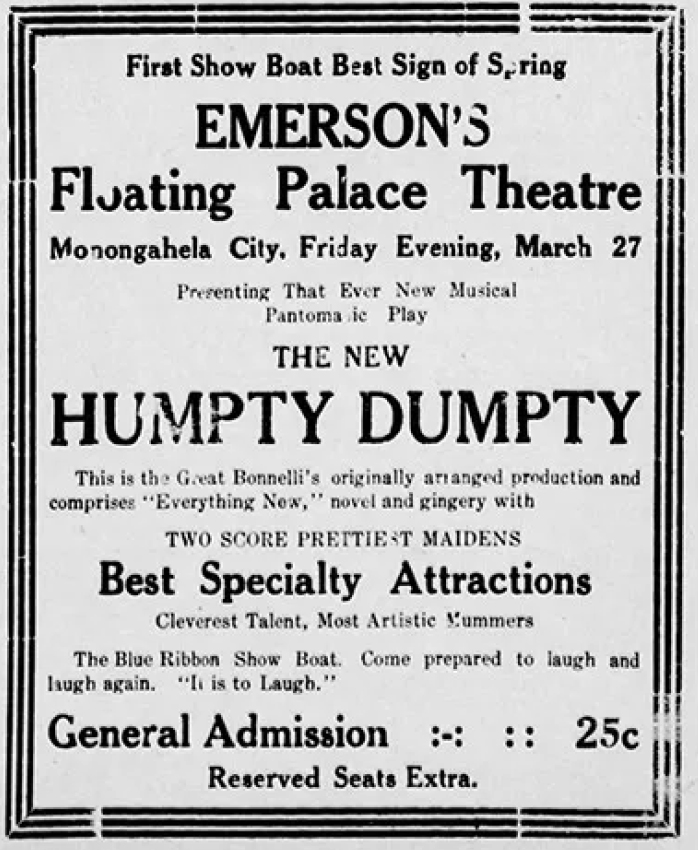

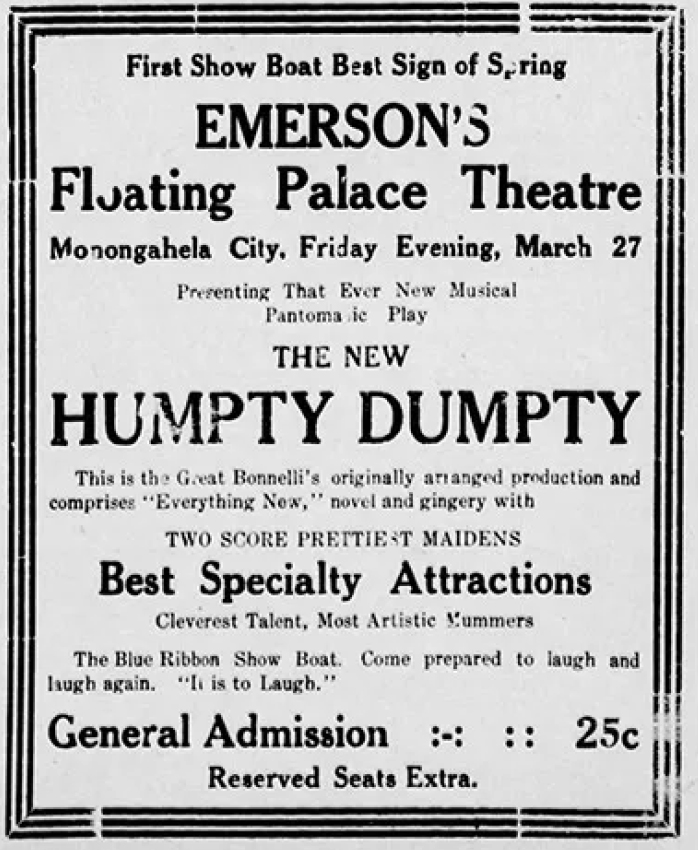

Ad for Emerson’s Floating Palace published in the Monongahela, Pennsylvania, Daily Republican March 26, 1908. Via Newspapers.com.

Ad for Emerson’s Floating Palace published in the Monongahela, Pennsylvania, Daily Republican March 26, 1908. Via Newspapers.com.

Part of the Gaches legend was his fondness for baseball. His former employees and other riverboat people recalled that Gaches recruited actors who were good players onstage and on a baseball diamond. The Gaches showboat crew played local ball teams in towns up and down the Ohio River.

Ralph and Beatrice Gaches were married in 1898. She was the daughter of a Meigs County, Ohio, judge. Despite having no children of her own, Beatrice taught the children of other showboat owners in makeshift classrooms aboard the showboats. “I attended school on the Water Queen. Mrs. Ralph Emerson Gaches was with the troupe that summer and every day she held school on the stage,” wrote Capt. Billy Bryant in his memoir.

Cincinnati home where Ralph and Beatrice Gaches lived in the early 1920s. Photo by David S. Rotenstein.

Cincinnati home where Ralph and Beatrice Gaches lived in the early 1920s. Photo by David S. Rotenstein.

Ralph and Beatrice Gaches split in the 1920s. He remained on the rivers and she built a small real estate business in Cincinnati. The number of showboats dwindled in the 1920s as radio and movie theaters spread across the country. The Depression that began in 1929 was a major economic blow to the showboat business.

Ralph Gaches went ashore, and by 1930 he was living in Chicago working in advertising and real estate. There, he briefly operated two showboats. Gaches bought one and renamed it the Cotton Blossom after his earlier boat. He commissioned another from a Wisconsin boat builder, which he named the Dixiana. Gaches ended his boating and entertainment career in 1934 when he sold the Dixiana.

After Gaches died in 1956 at age 75, obituary writers around the country connected his career to Ferber’s “Showboat.” Ferber wrote “Showboat” after spending several weeks on the Goldenrod. She named her fictional floating theater the Cotton Blossom after one of Gaches’ former boats.

Later Showboat spinoffs

Starting during Prohibition, Pittsburgh entertainment and hospitality entrepreneurs used showboats as a model to open floating casinos, speakeasies and nightclubs. In 1923, Downtown restaurant owner Frank Bongiovanni opened his Floating Palace on the Mon Wharf. Built by the John Eichleay Jr. company in Hays, Bongiovanni’s boat had a colorful history, especially after later operators renamed it the Show Boat in 1929. A raid by federal agents the following year made headlines for months and became a Pittsburgh organized crime legend.

The John Eichleay Jr. Co. built Bongiovanni’s Floating Palace in 1922. Bongiovanni tipped his hat to showboats by using a popular showboat name. Courtesy of the Heinz History Center Detre Library and Archives.

The John Eichleay Jr. Co. built Bongiovanni’s Floating Palace in 1922. Bongiovanni tipped his hat to showboats by using a popular showboat name. Courtesy of the Heinz History Center Detre Library and Archives.

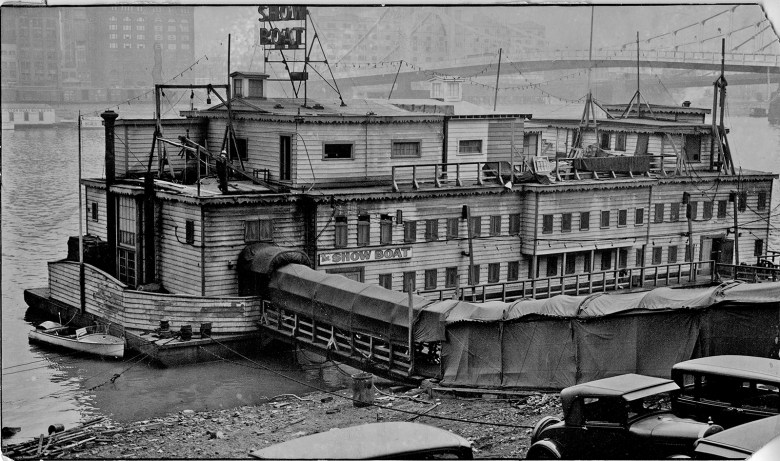

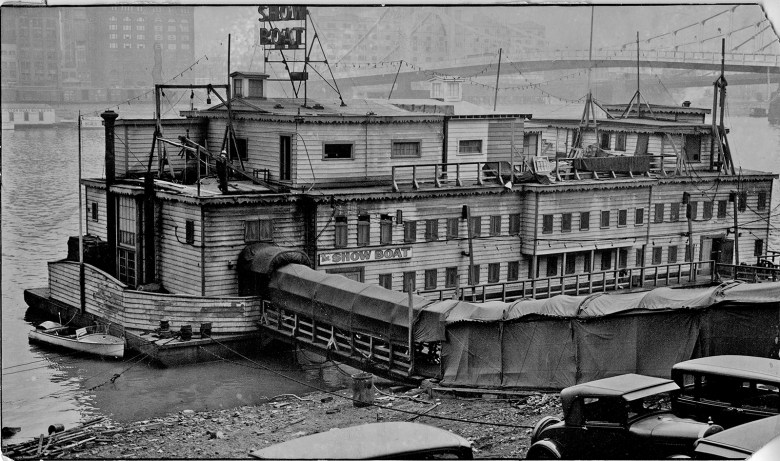

After gamblers George Jaffe and Art Rooney Sr. in 1929 took over the floating nightclub on Bongiovanni’s former Floating Palace, they renamed their floating casino and speakeasy the Show Boat. Courtesy the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

After gamblers George Jaffe and Art Rooney Sr. in 1929 took over the floating nightclub on Bongiovanni’s former Floating Palace, they renamed their floating casino and speakeasy the Show Boat. Courtesy the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

One week before the Show Boat raid, Allegheny County police raided the Manitou. Gaches had sold the boat to Walter Eichleay a few years earlier. The 1930 raid yielded multiple arrests on pornography charges.

Journalist Walter Liggett penned a colorful description of goings on aboard the Manitou. “There isn’t a form of depravity that hasn’t been put on a dividend-bearing basis in Pittsburgh, and even perversion is made to pay a profit,” Liggett wrote in a widely read 1930 magazine article. “For months a boat called the Manitou, which docked in the Monongahela River near the foot of Wood Street, pulled out into the river every night with from three hundred to five hundred cash customers aboard and a nightly ‘show’ was put on which consisted of naked dancing and indescribably vile motion pictures.”

Bobby Whites’ floating nightclub moored in the Allegheny River. Photo courtesy Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh Libraries via historicpittsburgh.org.

Bobby Whites’ floating nightclub moored in the Allegheny River. Photo courtesy Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh Libraries via historicpittsburgh.org.

In the mid-1930s, Bobby Whites followed the Show Boat. A simple barge with a building on its deck moored in the Allegheny River, Bobby Whites was a floating satellite to its owner’s North Side café and speakeasy.

The Ship Hotel was another Allegheny River establishment. It operated between 1938 and 1954 and offered barbecue, music, dancing and cheap rooms.

Ship Hotel moored in the Allegheny River. Photo courtesy Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh Libraries via historicpittsburgh.org.

Ship Hotel moored in the Allegheny River. Photo courtesy Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh Libraries via historicpittsburgh.org.

In Blawnox, entrepreneur Tom Lugen docked a retired steamboat next to the old Montrose Hotel in 1963. He called the new place the Thunderbird Boatel. The “boatel” featured local and national bands. During its decade-long run it became a popular regional party destination.

Even Jim Zubik, the son of legendary river salvage boat business owner Charles Zubik (best known for his fleet of abandoned boats that for decades littered the three rivers), got into the showboat business. In 1951, he launched a short-lived venture he called the Showboat Café. Moored in the Allegheny River near the Ninth Street (Rachel Carson) Bridge, the nightclub featured live music and steak dinners.

Fast forward to the 1990s when plans were floated to allow riverboat gambling. Though a proposed riverboat casino at Station Square never materialized, in 2009 Rivers Casino became the city’s first legal gambling complex.

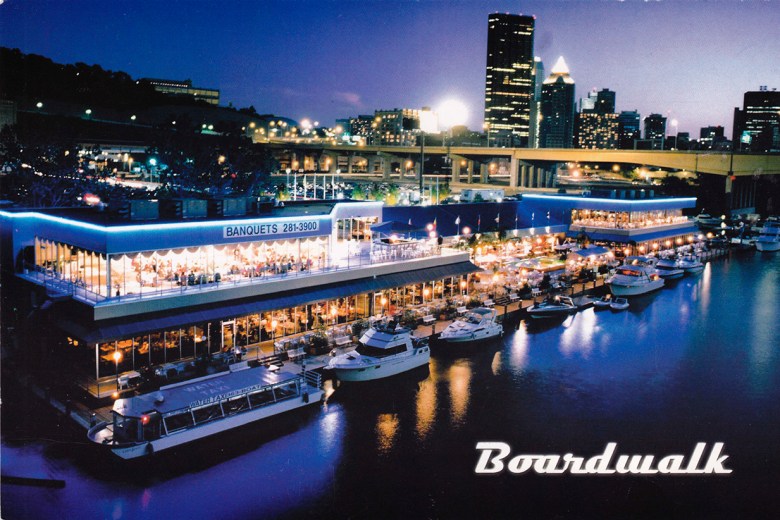

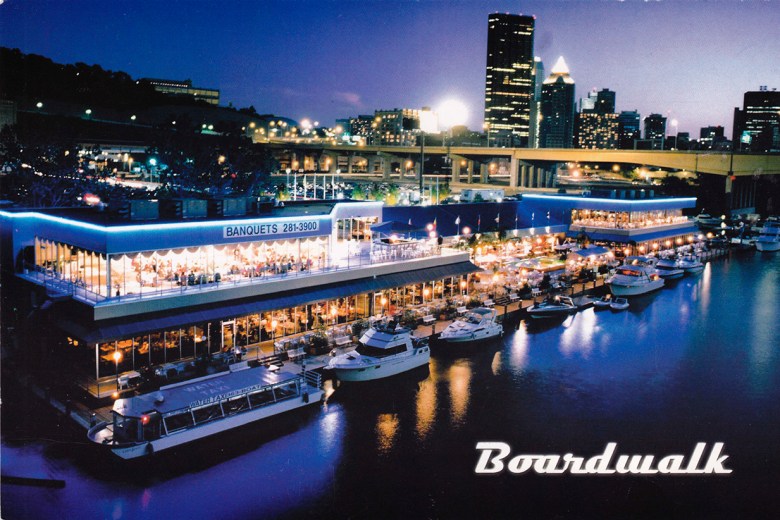

Pittsburgh’s last grand floating entertainment experiment ended in 2007 when the Boardwalk complex closed after going bankrupt. “I built a huge place — it was built out of four jumbo deck barges,” recalled owner Tom Jayson in a 2024 interview.

Postcard advertising the sale of the Boardwalk complex. Courtesy of Maggie Jayson.

Postcard advertising the sale of the Boardwalk complex. Courtesy of Maggie Jayson.

Located in the Strip District at the foot of 15th Street, the Boardwalk opened in 1991. Its clubs included Donzi’s, Crewsers and Buster’s Crab.

Earlier this year, Riverlife launched Pittsburgh’s latest floating recreational space, Shore Thing, on the Allegheny River between the Roberto Clemente and Andy Warhol bridges. Though it lacks the atmosphere and colorful characters that once marked Pittsburgh’s floating pleasure palaces, Shore Thing builds on a popular formula that leverages one of the city’s strongest assets: its rivers.