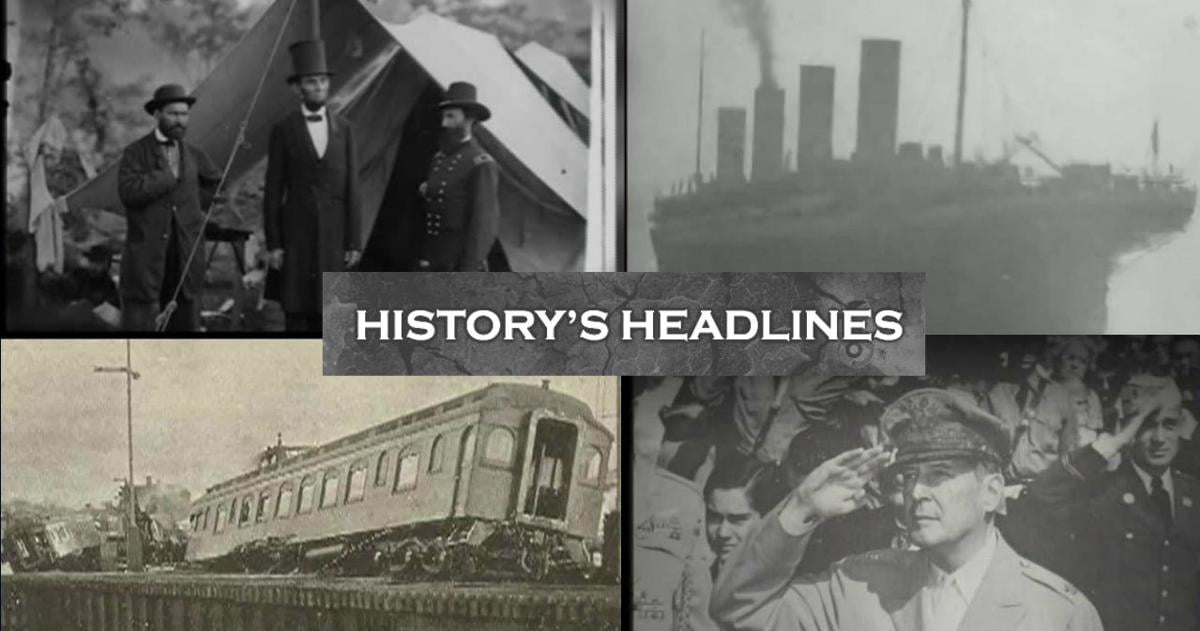

Quiet was probably not a word you could apply to the Allentown Iron Works in the late 1860s. Located in the city’s Sixth Ward, it consisted of what one local newspaper called “four immense stacks, four large cast houses, three coal-houses, storehouses, engine-houses, and other buildings necessary for carrying on the heavy business of the furnace.” The 600-man workforce was made up largely of local Pennsylvania Germans and Irish immigrants who worked in shifts.

Allentown Iron Works, 1860

Allentown, 1762-1987: A 225-year history. Lehigh County Historical Society

The iron works’ major product was railroad rails for the booming market. On September 6, 1869, the press was reporting on the arrival of the first westbound train in San Francisco. Founded in 1846, the Allentown Iron Works were the first of their kind in the city.

But in the early morning hours of September 7, 1869, the factory was making another kind of news, and it was not good. At 1 a.m. an engineer with a lantern came into the waste room of furnace number 3.

What exactly he was doing there the press did not speculate on. But whatever it was, his lantern lit something in the room afire. “The fire then communicated to the engine-house and quickly spread in each of the engine-houses,” noted the Allentown Register, whose article was reprinted a day later in the New York Times, “involving in one sheet of flame the whole mass of the buildings and presented a sight fearful to look upon. The seething, hissing noise of the escaping steam and rushing of hot air, the white flame and sulfurous clouds of smoke formed a scene as appalling as it was grand.”

Allentown’s various volunteer fire companies quickly attempted to get the fire under control. But they met many obstacles. The ground was described as “hilly,” and, coupled with the “lateness of the hour,” it made putting out the blaze difficult. No lives were apparently lost, but engineer William Scanlin, a resident of the Fifth Ward, had his shoulder blade broken as the result of a beam falling on it.

Fortunately for the owners, the property was heavily insured. By the next day workers from Hokendauqua, Catasauqua and Bethlehem were recruited from around the area to begin the cleanup and repair.

Allentown Iron Works, 1889

Allentown, 1762–1987: A 225-year history. Lehigh County Historical Society

The newspaper reported that it was believed after an inspection that two of the stacks could be saved. “If they are successful,” concluded the article, “and if the stacks can be saved from the disaster resulting from chilling, it will besides give employment to a large number of the hands.”

Historically the site had an importance of its own. It was here that Allentown was introduced to the Industrial Age. The individual who did that was Samuel Lewis (1805-1897). These details of Lewis’s life came from the Morning Call in 1897 in his obituary.

Portrait of Samuel Lewis

History of the Lehigh Valley, 1860

The information probably came from his grandson, Fred Lewis, a Progressive Teddy Roosevelt Republican who was also the mayor of Allentown and friends with Morning Call publisher David A. Miller. Mayor Lewis also happened to bear a striking resemblance to the president, which he would play up at times by growing a bushy mustache and wearing pince-nez eyeglasses. At a campaign stop in the city, TR was said to have been stunned when he was greeted this way by the mayor.

Fred Lewis

Men of Allentown, 1917

Of Scotch-Irish background, Samuel Lewis’s grandfather William came to America in 1735. He settled at East Nantmeal Township in Chester County. Later, when Samuel Lewis was 7 his family moved to a property called Springtown Forge.

Lewis’s father died when he was 17. In 1822 he left home and went to work at Coleman’s Elizabeth Furnace in Lancaster County. After their deaths he worked for the Ammons family in Pine Grove, Lebanon County. “By this time, he was thoroughly grounded in all the details of the iron business, all of his former employers having been well-known iron masters,” his obituary states.

Moving to Lehigh County, Lewis worked for Stephen Balliet and Samuel Helfrich at the East Penn Forge and Furnace as a superintendent. It was located at the foot of the Blue Mountains behind Slatedale and later known as Balliet’s Furnace. In 1829 he married Elizabeth Balliet with whom he had 10 children, nine of whom survived into adulthood. At his wife’s death in 1864 he married her sister, Harriet.

By 1832 his attention was attracted to the growing anthracite coal business. Lewis left for the coal regions and soon was mining and shipping coal to Boston, Baltimore and other east coast cities.

Finally in 1846, Lewis, believing that it was time, decided to build two iron furnaces in Allentown. He began them in May, and they were finished in October. They proved spectacularly successful, netting him $80,000.

Like David Thomas, who Lehigh Canal builders Josiah White and Eriskine Hazard brought over from Wales and created the first commercially successful anthracite coal powered furnace at Catasauqua at the Crane Iron Works in 1840, Lewis also saw the possibilities of the Lehigh Valley as an iron making center.

Crane Iron Works, Catasauqua

In 1845, a year before he created his own iron furnaces, Lewis was approached by representatives of “a prominent and wealthy shipping firm of Philadelphia who were on the alert for investments, to make an examination of the Lehigh Valley as a location of an anthracite furnace for the use of anthracite coal.” This may be what inspired Lewis to build those early furnaces.

After discussions with Lewis that showed his knowledge of the region’s potential, the Allentown Iron Company was created. Among its partners was Henry King, the local congressman. The firm Haywood & Snyder supplied the machinery.

Samuel Lewis was to remain the superintendent of the Allentown Iron Works until 1878. If the fire of 1869 caused any serious problems, the iron boom was apparently not considered worth mentioning. The obituary also makes no mention of the fire or of the success of Bethlehem Steel in replacing steel rails with iron rails that eventually largely lead to putting Allentown’s iron furnaces out of business.

Allentown Democrat, 1897

According to an article in the April 14, 1897, edition of the Allentown Democrat, the ailing Samuel Lewis at age 93 was the richest man in the city with a fortune of $800,000, most of it safely secured in U.S. government bonds. The Democrat hoped Lewis would soon be well, but he died on July 31, 1897. His funeral was held at the First Presbyterian Church.