John Funk was relaxing next to an animatronic inflatable gift box from which a penguin periodically rose when the gutter cleaning guy showed up.

In mid-November in leafy McCandless, gutter guy’s arrival was not shocking. But John, 23, sat up in his lounge chair and glared hawk-like out the front window. The handyman was raising his ladder right in front of a 6-foot inflatable turkey.

“Watch the turkey,” John warned, though the contractor would not likely hear him through the window. “You break it, you buy it.”

We’re local reporters who tell local stories.

Subscribe now to our free newsletter to get important Pittsburgh stories from Public Source reporters sent to your inbox three times a week.

Inflatables have been an ever-expanding part of John’s life since 2006, and they often dominate the yard of his family’s home. In the run-up to Halloween, he had 70 blow-up ghosts, pumpkins and other characters in the back yard alone.

“I like how they look. I love how they light up,” he explained. “I love the sound of the fans.”

John Funk stands in front of Thanksgiving inflatables on Nov. 15, at his family’s home in McCandless. Funk has started John’s Funky Inflatables, renting repairing, and selling the whimsical fan-puffed yard decorations. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

John Funk stands in front of Thanksgiving inflatables on Nov. 15, at his family’s home in McCandless. Funk has started John’s Funky Inflatables, renting repairing, and selling the whimsical fan-puffed yard decorations. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

His love drives John’s Funky Inflatables, which — for now — is more of a hobby than a business. He’ll rent, sell, repair or install pretty much anything involving a fan, fabric and whimsy. He plunges his modest proceeds back into his collection of some 400 inflatables, from a 3-foot wedding cake to a 20-foot Easter Bunny — nearly all bought used or on sale.

Going pro could supplement the paycheck he collects for working a few mornings a week at a household products store and the Social Security he receives as an autistic adult. He’s approaching one of those forks in the road common in the lives of people with disabilities at which they must balance the satisfaction of paid work and the relative security of government benefits.

Matt Bailey often hears well-meaning people tell their disabled loved ones, “You cannot work, you’ll lose your benefits.” Not true, said Bailey, a benefits supervisor and training specialist at Achieva Family Trust. “They don’t realize that you can work on these benefits.”

There are rules, though, regarding how much a person can earn and what they can own without losing government benefits. Without those benefits a person can be at the mercy of the market, where the law provides some protection, but no guarantees.

A note from Rich, the reporter: If you’ve been following Job One, you know that my son Zach, a.k.a. Z, works two part-time jobs. For a few years he got Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a Social Security benefit. An inconvenient rule: You can lose SSI if you have more than $2,000 in the bank. We hoped he’d eventually earn enough that SSI would dwindle to nothing, at which point he could start saving money.

The roaring 2020s

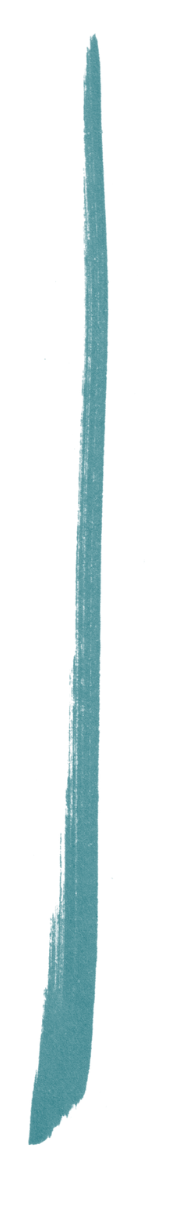

This decade has been good for people with disabilities who want to work.

According to a Federal Reserve Board report issued this year, 37.4% of disabled people aged 16-64 were working last year, up from 29.7% in 2009. The biggest part of that increase happened since COVID’s onset in 2020.

“It was across the board regardless of age, race, gender,” said Andrew Houtenville, research director of the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire. “All basically pushed past their historic highs.”

Source: Andrew Houtenville, research director of the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire

Source: Andrew Houtenville, research director of the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire

The normalization of remote work drove some of that, opening doors for people who might not have been able to make it to an office, Houtenville said. Widespread acceptance of flexible hours also opened up opportunities. A subtler factor: Immunocompromised people who did not previously seek accommodations at work began to do so, further legitimizing the requests of employees with other disabilities and needs.

John Funk, right, sits at his computer beside his sister Rebekah Funk on Nov. 15, in their family’s home in McCandless. Much of his inflatable collection is for rent online. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

John Funk, right, sits at his computer beside his sister Rebekah Funk on Nov. 15, in their family’s home in McCandless. Much of his inflatable collection is for rent online. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Houtenville said the employment rate of people with disabilities appears to have plateaued around 40%. “We’ve tapped out the post-pandemic workplace changes.” Will the gains hold? “We’ll see after the next recession.”

John Funk started this decade getting work experience through North Allegheny School District’s vocational program, cleaning in two locations. Vacuuming, though, left him feeling empty. His mother, Anne Funk, recounted a fateful 2021 commute.

“He looked over at me and said, ‘I don’t want to do this.’ … I told him, ‘You don’t have to do this anymore. … If it’s not going to bring you joy, you don’t have to do that.’”

But what did he want to do?

“Someday,” he said, “I’d like to be an inflatable expert.”

Back when he was 5, John arrived home one late autumn day to find an inflatable snow globe, with a penguin inside, in his front yard. His grandparents put it there as a holiday season joke. To him, it was a miracle. “Look what Santa brought for me!” he rejoiced.

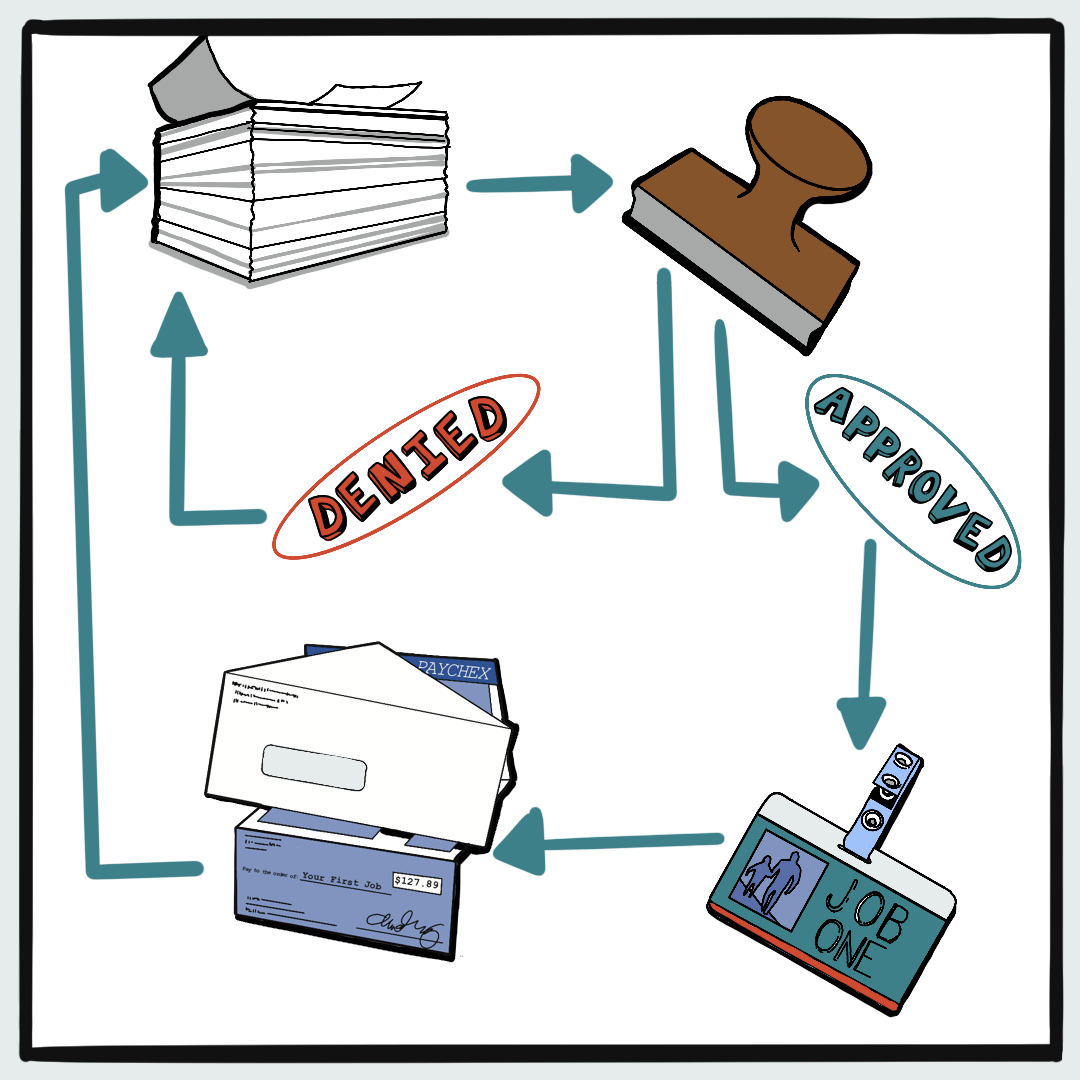

(Illustration by Andrea Shockling/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

(Illustration by Andrea Shockling/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

He began collecting in earnest at age 6, and never stopped.

After John soured on the cleaning job, his mother started job-hunting on his behalf, asking store managers if they were hiring. One manager, though, didn’t wait to be asked. She had noticed the young man admiring the store’s inflatables. The manager approached Anne and said: “You know, your son should work here.”

He applied that day. Now he does some stocking, works with the patio furniture and is in charge of setting up and arranging the inflatables.

Rich’s note: Z is autistic and has Tourette syndrome, and we’ve worked informally with supervisors on accommodations. When a repeated, loud noise at one of his workplaces led to outbursts, the supervisor said no to headphones, but didn’t object to noise-dampening ear plugs. When he struggled with personal space, we collaborated on a list of rules (i.e. “Do not sweep by people’s feet”) which he and I recited every day, for months, on the morning commute. We’ve practiced box breathing to curb his tics. He’s gotten annual raises and been rated a “good performer.”

Accommodations, within limits

Employers aren’t required to alter job duties for the benefit of a candidate or employee with a disability. Federal law including the Americans with Disabilities Act requires that employers make “reasonable accommodations” for disability.

What’s reasonable?

“It depends on what it’s going to cost, quite frankly,” said Sam Cordes, an employment lawyer who has sued on behalf of disabled workers. There’s no formula, he said, but courts tend to compare the cost of an accommodation to the resources of the company.

The U.S. Department of Labor has reported that job modifications often cost nothing, and those with price tags tend to come in around $300. A typical accommodation might be a mat to address pain from standing, earplugs for noise sensitivity or a screen reader for language processing disorders, said Amber Westwood, associate director of business services with Achieva Business Services.

If the accommodation isn’t expensive but the employer deems it disruptive, the process can be more difficult. Cordes takes the position that an employee with a disability can be required to perform the job just as well as anyone else, but that the employer can’t demand that the employee do the job the same way as everyone else. The employee should be allowed to perform the essential duties of the job in a way that works for them.

If an employee can’t handle the stress or hours of a job, though, courts may note that “an employee is not entitled to a rule-free or stress-free workplace,” he said.

A request for a shorter work day can result in a negotiation, said Lesley Beasom, associate director of competitive integrated employment at Achieva Support. “The employers that we work with are very reasonable,” Beasom said, and Achieva very rarely hears “no, we can’t do this.”

John Funk stands in front of a Christmas snow globe inflatable on Nov. 15, in his family’s yard in McCandless. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

John Funk stands in front of a Christmas snow globe inflatable on Nov. 15, in his family’s yard in McCandless. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Income and benefits

John is proud of the just-purchased snow globe inflatable in his back yard. There’s its sheer heft and its two fans, plus the repair he made on a critical leak. He’s most jazzed, though, about the price he got at Red White & Blue Thrift Store.

“This one actually retails for $369,” said Anne.

John: “No, now it’s on sale.”

Anne: “It’s on sale for $300.”

John: “No, it’s $299.”

He got it for $50.

John has put his inventory partly online, and says he’s grossed $445 selling inflatables. For rentals or installations (indoor only) he’ll accept donations to cover costs. The biggest return on investment, according to Anne, has been the skills he’s gained. With the help of family members and Joe Farrell of Evolve Coaching, he has learned to solder wires, swap out fans and lights, manage his website and work social media, where he has a strong following in the inflatables community.

If he starts to turn a profit, he’ll need to report that to the Social Security Administration. As earnings go up, SSI goes down, though more slowly. Earnings above a certain level bring SSI to zero, and if that’s sustained the benefit can end, along with the associated Medicaid eligibility. Assets persistently above $2,000 also trigger an end to SSI, and the government can demand a refund of benefits paid after that threshold was reached.

(Illustration by Andrea Shockling/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

(Illustration by Andrea Shockling/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

It’s not uncommon for the beneficiary or the Social Security Administration to make a mistake resulting in either overpayment or underpayment, sometimes to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars, according to Bailey. A benefits counselor can help work through bureaucratic processes and figure out health insurance issues that can come with benefits changes, he said. The cost of that service is covered by state funds.

People receiving SSI can be moved to the longer-term SSDI program for two reasons.

If they meet eligibility requirements, the adult child of a person receiving Social Security can receive benefits through the Disabled Adult Child program.

The disabled person’s work history can be long enough to trigger the Social Security Administration to move the worker from SSI to SSDI.

Rich’s note: Every month we’d send in Z’s pay stubs, and the Social Security Administration would calculate his benefit and pay it. We figured that would go on until eventual increases in work hours and pay whittled it down to nothing, and we’d be done. But over the summer, the government sent a hurricane of paperwork. The big takeaway: They wanted to check whether Z was still disabled, and if so, switch him to SSDI. We called his social worker and asked: What did it mean? The answer: A higher and stable monthly benefit, no asset limit and an eventual move from Medicaid to Medicare. But it all goes away if he consistently earns more than $1,690 per month next year. Z is secure, but with a ceiling.

According to the most recent available data on SSDI, there were 8.7 million people receiving the benefit at the end of 2023, of whom 35% were characterized as having primarily mental health-related disabilities. The average monthly benefit was $925.

John’s father, Shawn Funk, 62, a former public school teacher and the artistic director at the Pittsburgh Youth Chorus, plans to file for Social Security next year to qualify his son for SSDI. That would give John financial stability. That could also give Shawn more time to help out with John’s Funky Inflatables.

John Funk shows a jack-o-lantern inflatable on his computer on Nov. 15, at home in McCandless. He continues to grow his collection by buying used and on sale inflatables. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

John Funk shows a jack-o-lantern inflatable on his computer on Nov. 15, at home in McCandless. He continues to grow his collection by buying used and on sale inflatables. (Photo by Kirk Lawrence/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

“It’s sort of a self-sustaining passion that is going to go somewhere,” said Shawn. “John is only limited by the staff that he has — which is us, and we’re all pro bono,” he said, referring to the family.

John had shorter-term concerns. This time of year he usually does half of the yard in Disney inflatables and the other half in a miscellaneous array, but not this month.

“I’m going to be doing a gingerbread theme in front for Christmas,” he said. He has an inflatable gingerbread-style windmill, teeter totter, house, archway, cake and array of people.

Business expansion can wait. “I’m happy with it where we are now.”

Rich Lord is Z’s father, and the managing editor of PublicSource, and can be reached at rich@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Angela Goodwin.

RELATED STORIES

Keep stories like this coming with a MATCHED gift.

Have you learned something new today? Consider supporting our work with a donation. Until Dec. 31, our generous local match pool supporters will match your new monthly donation 12 times or double your one-time gift.

We take pride in serving our community by delivering accurate, timely, and impactful journalism without paywalls, but with rising costs for the resources needed to produce our top-quality journalism, every reader contribution matters. It takes a lot of resources to produce this work, from compensating our staff, to the technology that brings it to you, to fact-checking every line, and much more.

Your donation to our nonprofit newsroom helps ensure that everyone in Allegheny County can stay informed about the decisions and events that impact their lives. Thank you for your support!

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.