Regional water activist Eddie “Trash Fish” Olschansky moors his “Bessie” sculpture to a floating dock along the Cuyahoga River in downtown Cleveland. On November 12, Olschansky debuted the plastic sea monster during a rally at Settler’s Landing Park against plastic pollution in local waterways, a trend affecting Ohio statewide as manufacturing takes hold.

Regional water activist Eddie “Trash Fish” Olschansky moors his “Bessie” sculpture to a floating dock along the Cuyahoga River in downtown Cleveland. On November 12, Olschansky debuted the plastic sea monster during a rally at Settler’s Landing Park against plastic pollution in local waterways, a trend affecting Ohio statewide as manufacturing takes hold.

On the frigid night before he jettisoned his plastic-made sea monster sculpture “Bessie” into the local river feeding Lake Erie, Eddie Olschansky shared to his Instagram story a photo of another spectacle hovering above Ohio’s defining water feature: the aurora borealis. “That’s a good omen for tomorrow,” the local ecological activist wrote on the account he runs under his Trash Fish moniker. “I love them northern lights!”

The following day, November 12, opened to heavily overcast skies and high winds as the members of activist groups, including the People Over Petro Coalition (POPCO), Earthworks, Third Act Ohio and The Climate Reality Project’s NE Ohio Chapter, gathered to see a plastic sea monster cruise the Cuyahoga River. Members of the organizations passionately made their case against plastic pollution as part of a “Rally for a Plastic-Free Cleveland” event along the river’s east bank at Settler’s Landing Park.

“Particles are all over the Great Lakes, but one of the highest plastic concentrations in the world is in Lake Erie,” Cheryl Johncox, a POPCO regional coordinator for the Columbus area, told a crowd of roughly 60 who gathered within the small downtown park. She referenced research pointing to Erie’s status as the second most plastic-contaminated of the Great Lakes, the result of a yearslong uptick in man-made particulates fueled in part by Ohio’s plastic economy.

Via the ironic temporary reintroduction of plastic to one of Northeast Ohio’s defining water features, the event was designed to draw attention to the dangers of plastic pollution on the natural environment and human health. The crowd, primarily composed of activists, came in hopes of catching sight of the 15-foot-tall floating monster sculpture, a brightly hued amalgamation of petroleum-based products that Olschansky has pulled from the river.

Olschansky designed Bessie to reference the “Bessie the Lake Erie Monster” legend dating back over 200 years along the shores of Ohio and Michigan, but the materials are all modern. As with previous trash sculptures, Olschansky has essentially collaged together the more notable pieces of debris he’s collected from the river. “A big part of the spin was a Little Tykes children’s easel set that we cut up.”

Olschansky designed Bessie to reference the “Bessie the Lake Erie Monster” legend dating back over 200 years along the shores of Ohio and Michigan, but the materials are all modern. As with previous trash sculptures, Olschansky has essentially collaged together the more notable pieces of debris he’s collected from the river. “A big part of the spin was a Little Tykes children’s easel set that we cut up.”

November 12 also coincided with the start of the two-day AMI Plastics World Expo North America, a trade show and networking event at the Huntington Convention Center that promised attendees “access to the largest gathering of companies from the plastics compounding, recycling, extrusion, and testing sectors in North America.” The polymer industry’s statewide gross domestic product was $50 billion in the Buckeye State as of 2019, according to a market trend report from the Plastics Industry Association.

However, participants at the November 12 protest event like Kathy Smachio, member of the Cleveland Heights Green Team and affiliate of anti-single-use group Beyond Plastics, believe that plastic manufacturing should be reduced and more critically discussed in the Buckeye State due to the overriding health consequences it carries.

Signs at the November 12, planned as action against the two-day 2025 AMI Plastics World Expo at the Huntington Convention Center downtown, referred to the plastic production process as “waste colonialism” and stated “recycling is really an excuse to make more plastic.”

Signs at the November 12, planned as action against the two-day 2025 AMI Plastics World Expo at the Huntington Convention Center downtown, referred to the plastic production process as “waste colonialism” and stated “recycling is really an excuse to make more plastic.”

“The lifecycle of plastics is filled with dangers and unforeseen consequences to the health of all life on Earth,” Smachio told those in attendance as Bessie bobbed in the background. “Plastic starts with drilling and mining for fossil fuels. These actions. . . release huge amounts of greenhouse gases, toxins, pollutants and pollution into grass and soil.”

Kidney and liver diseases, cardiovascular health problems, metabolic diseases like diabetes and obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, reproduction-related problems, birth defects and abnormalities, immune system suppression and allergies; residents are putting themselves at risk of a litany of health effects, Smachio continued. It’s the result of exposure to microplastics, she argued.

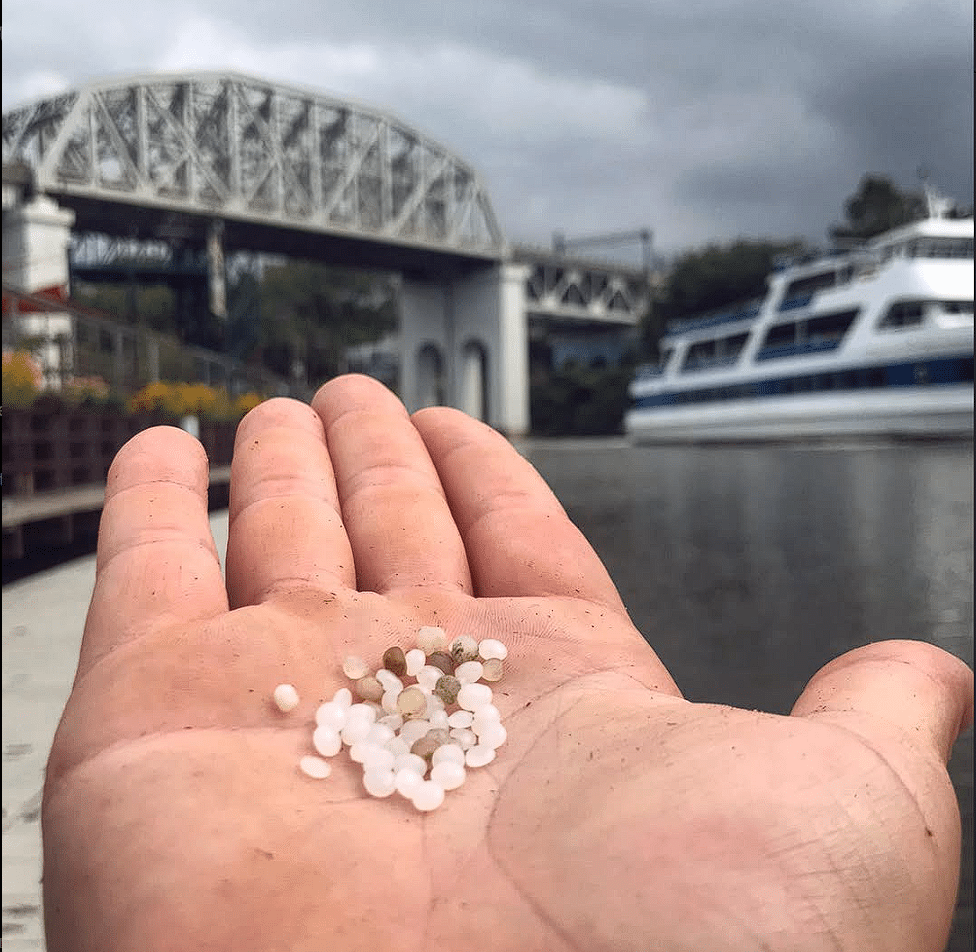

The same is true for the daily operation and eventual disposal of plastics designed for either short- or long-term usage, the latter of which are likely to remain in landfills for several centuries, but Olschansky said the worst offenders are what he has dubbed “zero-use plastics.” He was referring to small pods of lab-made polymer compounds that industry members and watchdog groups have been calling “nurdles” since sometime in the 1960s. In 2021, The Guardian called nurdles “the worst toxic waste you’ve probably never heard of.”

These synthetic pellets are essentially the building blocks for many plastic products, capable of taking a variety of forms after they hit an industrial heat press, but due to their size they often find their way into Olschansky’s net as it scours the river and lake.

Nurdles are small, seemingly innocuous beads of unmelted plastic that Olschansky calls “zero-waste plastic” because they are often small enough to slip through the cracks in factory infrastructure and then pipelined to the Cuyahoga. (Photo courtesy of Trash Fish on Instagram.)

Nurdles are small, seemingly innocuous beads of unmelted plastic that Olschansky calls “zero-waste plastic” because they are often small enough to slip through the cracks in factory infrastructure and then pipelined to the Cuyahoga. (Photo courtesy of Trash Fish on Instagram.)

“When you drink your water, beverages made with water, when you eat fish, when you consume fish that’s processed with water, you’re almost certainly ingesting plastic,” Johncox told attendees at the rally. “Plastic can bioaccumulate. That means it can build up in the bodies of animals (that’s us). Research shows plastic is all over our bodies.“

“Litter ain’t the issue”

On November 12, meanwhile, Olschansky was unaware of what any of his fellow activists had to say as he leisurely paddled his kayak down the river in the background so the rally attendees could peer and cheer at his creation. The wind drowned out any chance he had of hearing his fellow climate activists as he towed his 15-foot-long plastic sea monster along the Cuyahoga River from the stern of his kayak, but the words he offered after he’d docked downstream echoed many of their sentiments.

“All of the shoes — that’s been a long time collected,” Olschansky explained, “and it kind of shows people that littering really isn’t the issue. No kid wanted to lose their favorite basketball or favorite toy or whatever to the river. It just ends up on the street and then it floats down to the river. So we try to show people that it’s not all styrofoam and Taco Bell wrappers that people throw on the ground.”

“For the safety of myself and others, no,” Olschansky said when asked if he could name which local companies he has identified as most frequently polluting the river. “But there are sites.”

For now, the focus is on cleaning and restoration. As Olschansky prepares his kayaks for winter storage, he hopes to open next season on the water as a fully licensed 501(c)(3) nonprofit with additional grant opportunities and, ideally, a tour guide who serves in a similar capacity to him.

“We had almost 300 volunteers (this year),” he explained, “and I think about this time last year we had about 750 inquiries.”

Local legends

The concept for the sculpture came to Olschansky roughly a half-decade ago. It’s loosely based on regional folklore, dating back to 1817, involving a creature whose sightings are reminiscent of Scotland’s mythical Loch Ness Monster.

Olschansky started publicly calling attention to his efforts to sift through Lake Erie’s waters in 2019, and frequently repurposes the flashier bits of garbage he’s found in the lake to create eye-catching trash sculptures inside aquariums. He started ideating Bessie in 2020, but an opportunity never presented itself to the activist until POPCO and other groups started planning the rally against the plastics expo in summer 2025.

“Originally, the idea was for me to have a big sign that I towed with my kayak,” Olschansky told The Land following the rally. “After much discussion, I pitched the idea of a bigger sculpture that moves on its own for safety reasons. (POPCO) jumped on the idea and helped fund it, and Ingenuity Cleveland gave us the space to work on her.”

Together with multidisciplinary Cleveland artist Ian Petroni and local painter Max Unterhaslberger of High Key Murals, Olschansky said the creatives built Bessie in Ingenuity’s space between September and October.

Olschansky can frequently be seen in the warmer months using his polyethylene craft for good, leading teams of net-wielding volunteers in combing the river for man-made detritus, mainly plastic. That’s where he found the dozens of Crocs, deflated basketballs and discolored children’s toys that make up some of Bessie’s more visible design elements which, according to Olschansky, point to the root cause of the pollution: plastic production.

Olschansky’s online bios posit a rarely heard take on plastic pollution: “litter ain’t the issue.” As Trash Fish, he preaches the dangers of plastic production as the root cause, with recycling efforts paling in effectiveness to abstaining from polymer-based products.

Olschansky’s online bios posit a rarely heard take on plastic pollution: “litter ain’t the issue.” As Trash Fish, he preaches the dangers of plastic production as the root cause, with recycling efforts paling in effectiveness to abstaining from polymer-based products.

Olschansky stresses the enjoyable aspect of the volunteer efforts he offers throughout the watershed that feeds into the river and, ultimately, the lake.

“Getting trash out of the river is important to Trash Fish, but accessibility to the river is probably paramount above that,” Olschansky explained. “I got into this work because I’m recreating on the river. . . I know that a kayak is expensive to buy — having a car to transport it down to the river, having space at your house to store it, all of these are impediments for Clevelanders to enjoy this great river.”

Olschansky concluded that by bolstering people’s access to the river and their ability to enjoy spending time on it, they then notice when the environment is awry and understand how to heal the river more naturally.

“We want everybody to come down. No matter where you’re from or how much is in your wallet, you can come out, connect with that river, learn something to give back, and hopefully once you’re on dry land you’ll want to continue your efforts.”

Trash Fish’s volunteer sign-up is currently down as Olschansky finds himelf inundated with volunteer requests ahead of the summer 2026 season, but as the activist grows his project into a nonprofit readers can find more news on the organization’s official website.

Anyone can report sightings of Bessie online. The sculpture will make further official appearances at upcoming Ingenuity Cleveland events.

All photos courtesy of Collin Cunningham unless stated otherwise.