TOLEDO, OH — This year’s harmful algae bloom in western Lake Erie was among the mildest in a decade, but the improvement may owe more to favorable weather conditions than fundamental reductions in regional nutrient pollution from agriculture.

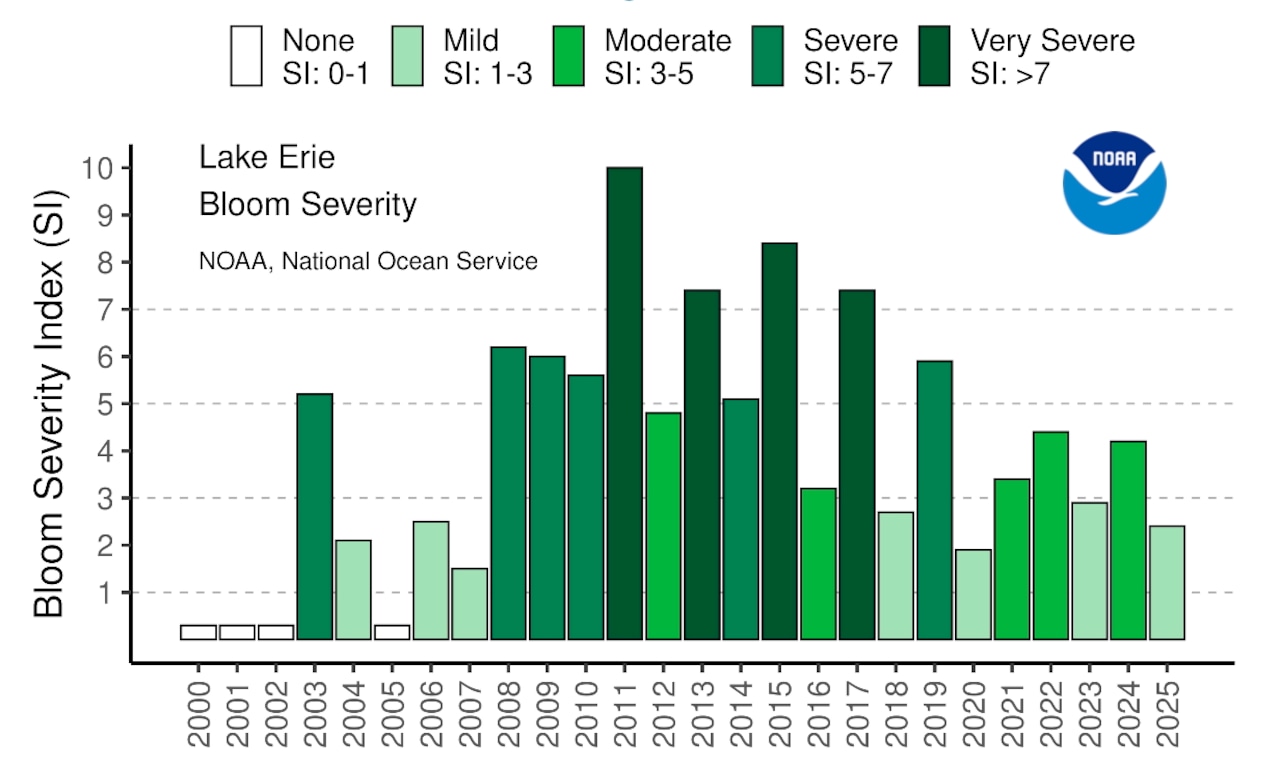

On Dec. 4, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration rated the bloom a 2.4 on a 10-point severity scale, well below the long-term average. Satellite imagery showed a bloom that formed slowly in July, peaked in late August and collapsed in September.

Forecasters had predicted a 2025 bloom severity of 3 in June and the final result fell below that, spreading across about 411 square miles. It follows a stronger 2024 bloom that reached a 4.2 on the 10-point scale and spread across roughly 626 square miles.

Lake scientists say the assessment indicates year-to-year changes in severity remain closely tied to weather and Maumee River discharge.

A NOAA Lake Erie harmful algae bloom severity index for 2000-2025. The index is based on the amount of cyanobacteria biomass over three 10-day composites. The 2025 bloom had a severity of 2.4,

A NOAA Lake Erie harmful algae bloom severity index for 2000-2025. The index is based on the amount of cyanobacteria biomass over three 10-day composites. The 2025 bloom had a severity of 2.4,

which is considered mild.NOAA

Tom Bridgeman, an ecology professor and director of the University of Toledo Lake Erie Center, said the mild severity of this year’s bloom is “primarily due to the reduced flow of water from the Maumee River due to relatively dry spring and summer weather.”

“However, there is data suggesting that the concentration of nutrients in the river is also beginning to decline in recent years, which would presumably be due to the increased adaption of agricultural best management practices by producers in the watershed,” Bridgeman said.

“There is a lot of ’noise’ in the data which means it may take several more years of improvement before we can clearly see the difference being made by farmers, but it looks like things are moving in the right direction.”

Ohio’s latest Nutrient Mass Balance Study, published in late 2024, found that nonpoint agricultural runoff continues to account for about 90 percent of the Maumee River phosphorus load and swings in loading remain tightly tied to wet and dry years.

The study notes that while millions in conservation funding have flowed into the western basin, “a delay is expected in observing load reductions as the impact of legacy nutrient management practices wanes over time.”

Nonetheless, this year’s bloom severity fell within what’s being called an “acceptable” range by some scientists.

“A 3 is the target,” said Ohio Sea Grant Director Chris Winslow on Aug. 27 during a presentation at Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory. “We’d probably like to see a little less green, but this is something that we would call ‘acceptable’ given the condition and what we use the watershed for.”

Winslow said that long-term watershed monitoring data shows dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) — the form most readily used by cyanobacteria — is trending downward while particulate phosphorus has increased in recent years, possibly due to changes in tilling practice.

Chris Winslow, director of Stone Lab, holds water samples from Lake Erie on Aug. 28, 2025.Garret Ellison

Chris Winslow, director of Stone Lab, holds water samples from Lake Erie on Aug. 28, 2025.Garret Ellison

Winslow attributed reductions in dissolved phosphorus to farmers in the Maumee River basin adopting recommendations such as subsurface fertilizer placement and avoiding applications ahead of rainfall.

“We think we’re seeing the recommendations for farmers start to grab hold,” he said. “We are seeing success.” Nonetheless, he expressed frustration with cuts to the H2Ohio program — which state lawmakers cut by about $105 million over the next two years— raising concerns that reduced incentives could slow adoption of runoff-reducing practices.

Winslow also noted that internal phosphorus released from lake sediments contributes only a small fraction of bloom-fueling nutrients — about 3-to-7 percent depending on conditions — meaning watershed inputs continue to dominate the system.

At a Nov. 19 water quality roundtable in Hardin County, Ohio, convened by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources (IJNR), farmers said fertilization and nutrient conservation practices have improved substantially over the past decade, but adoption is uneven.

More farmers are taking advantage of H2Ohio subsidies to plant cover crops and change tillage practice. However, Jeff Duling, a no-till and strip-till farmer who participates in the state program said some older farmers will probably have to “die off” before a younger generation sees the value in changing nutrient management techniques.

Farmers also warned that federal upheaval is causing disruption. Edge-of-field monitoring — the main source of real-world runoff data — has been reduced due to staffing cuts at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) arm of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A USDA ARS edge-of-field monitoring station at the Chris Kurt demonstration farm in Dunkirk, Ohio, Nov. 19. 2025. (Garret Ellison | MLive)Garret Ellison

A USDA ARS edge-of-field monitoring station at the Chris Kurt demonstration farm in Dunkirk, Ohio, Nov. 19. 2025. (Garret Ellison | MLive)Garret Ellison

“They’re shutting down those sites,” said Kris Swartz, a Wood County farmer who chairs the Ohio Agriculture Conservation Initiative (OACI). “Maybe they’ll come back in the future but there’s gonna be a data gap.”

“We always say we’re doing science-based farming. We want that science to prove our practice,” Swartz continued. Without the edge-of-field data, “ultimately, it’s going to lead to… not having as much confidence in the decisions we’re making and maybe making the wrong decisions because that’s not proving out the practices we’re doing.”

Bill Kellogg, a Hardin County soybeans, corn and wheat farmer who demonstrates conservation techniques, said the H2Ohio subsidies just about cover the cost of the practices.

“We’re not making money on this,” Kellogg said. “We’re not getting rich.”

Independent of the bloom forecast, lake scientists warned that recent federal disruptions are undermining the region’s ability to track the bloom and evaluate improvement progress.

The NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab in Ann Arbor has lost roughly 40 percent of its staff due to Trump administration staffing cuts and other federal cuts have hampered toxin monitoring and field sampling, said Greg Dick, director of the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research at the University of Michigan.

Elsewhere, some U.S. Geological Survey stream gages essential for calculating Maumee River phosphorus loads were also briefly shut off during federal budget disputes. The annual NOAA algae assessment itself was delayed this fall due to the shutdown.

Advanced early warning devices known as environmental sample processors, or ESPs, weren’t deployed in the lake this year. The devices transmit water sample data to labs in real-time and warn drinking water systems when algal toxins are forming.

The bloom is filled each year with microcystin, a liver toxin that can sicken humans and animals — particularly dogs, which are sometimes killed by swimming in scum-covered water.

The algal toxins pose a risk to drinking water systems such as Toledo, which draws water from an intake in Lake Erie. Research shows that algal toxins deposited by waves can concentrate on the beach and persist for almost a month. Waves and wind can also aerosolize cyanotoxins, creating an exposure route for people who aren’t exposed to lake water.

In the meantime, farmers say they’re doing what they can to manage nutrients and make a difference in water quality.

Ohio conservation farmers Jerry McBride, (left) and Kris Swartz, (right), speak to journalists at the Bill Kellogg farm in Hardin County, Nov. 19, 2025.Garret Ellison

Ohio conservation farmers Jerry McBride, (left) and Kris Swartz, (right), speak to journalists at the Bill Kellogg farm in Hardin County, Nov. 19, 2025.Garret Ellison

“I see the trend in my environment, I see more farmers doing the same things we’re doing. We’re doing a better job,” said Swartz.

“We absolutely have some responsibility to deliver as clean of water into that water system as we can. I think more farmers are doing it and I think we are making a difference,” Swartz said. “Is it a difference that’s going to negate any algal blooms? No. We’re always going to have algal blooms.”