On the evening of Oct. 30, Carnegie Mellon University professor Edda Fields-Black received the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for History at Columbia University.

She was surrounded by family, friends and a cloud of witnesses who could attest to the meticulous scholarship she practiced in pulling “Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War” into the world. Fields-Black understood that the door she had walked through a decade earlier when she began her research had only gotten wider.

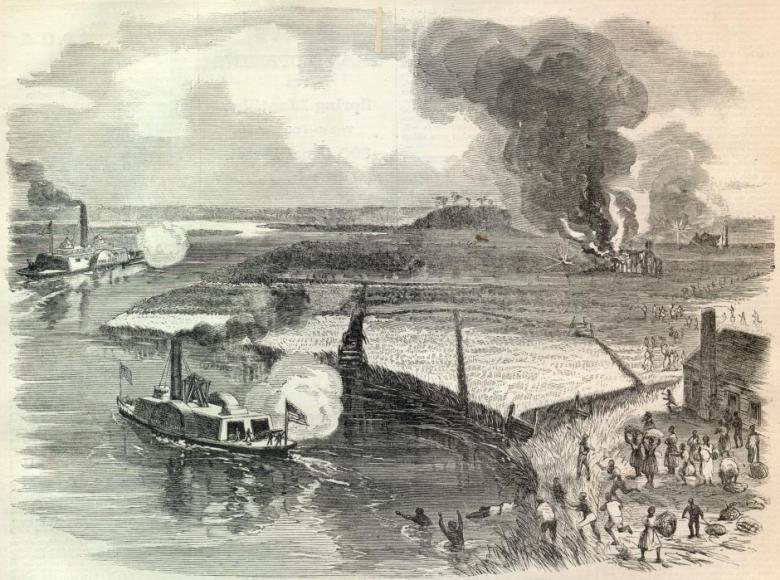

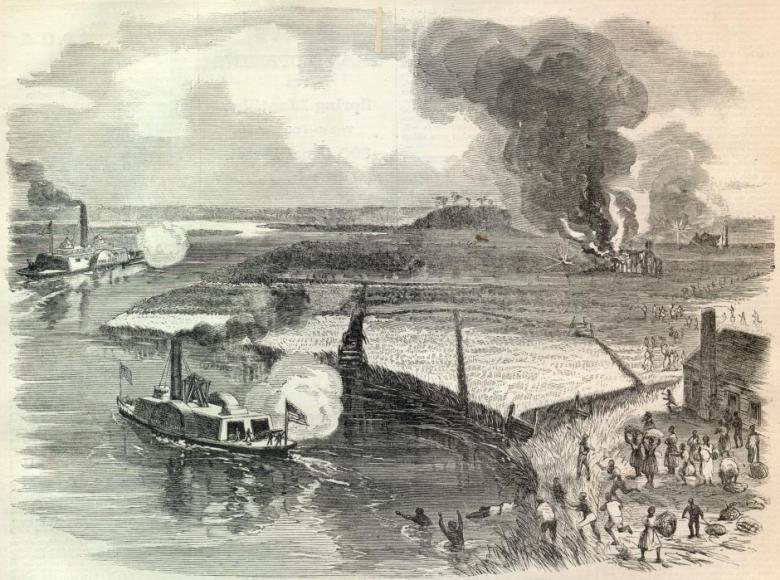

The result of her research is the most complete account of the liberation of 700 enslaved people from seven plantations along the Combahee River in South Carolina on June 1, 1863. On that day, the heroic Harriet Tubman led one of the most effective all-Black Union regiments in three federal gunboats up the Combahee River. They would not stop until their mission was accomplished.

The goal of Tubman and U.S. 2nd South Carolina Volunteers was to inflict maximum damage to the rice plantations that were vital to the Confederate wartime economy and to free everyone in bondage. Their “good trouble” is now considered the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history.

“Combee” is also the story of the Civil War as experienced by those with the most skin in the game — the enslaved who participated bravely in their own individual and communal liberation. It is a sympathetic portrait of some of the most fascinating, flawed and relentlessly optimistic people our slave-holding republic had ever produced. Harriet Tubman is just the tip of the spear, as it were.

Book cover for “Combee” by Edda Fields-Black. Courtesy of Oxford University Press. Photo of Pulizer Prize courtesy of Fields-Black.

As Fields-Black wrote in her book and has said in subsequent interviews, she wasn’t particularly interested in “writing another book about Tubman” just to add to the piles of exceptional biographies already in existance.

“I’m not a Tubman biographer,” she said during an interview with NEXT in her campus office at Baker Hall several days before embarking on her trip to New York with her family to claim her Pulitzer.

“The work I do is connected to the freedom seekers. It’s connected to the rice fields. It’s connected to slavery. It’s connected to the antebellum period in South Carolina. I get into the Harriet Tubman story because of that work. And then Harriet Tubman became an important part of it. I didn’t get into going to the Combee River because of Harriet Tubman.”

The problem for Fields-Black was that most publishers were interested in only Tubman biographies because of her rising pop culture profile at the time, so most passed on her pitch for a book rooted primarily in ongoing research about rice cultivation and the aspirations of enslaved people.

Her pitch was straight forward: Tell the story of the Combee raid from the perspective of the people who were freed. While Tubman played a sizable role in that liberation, she wasn’t the primary focus of the book as Fields-Black envisioned it.

“It’s like Gladys Knight and the Pips,” she said with a laugh, recalling the period when her pitches and analogies fell flat with the publishers. “It’s Harriet Tubman and the Freedom Seekers. They were like, no, it’s Gladys Knight! We don’t care about the Pips.”

“And you know, I’m trying to explain that this is new. I didn’t know everything then that I know now, but I knew if I could find these enslaved people, that was new, right? And they were, like, we don’t care about that. Give us Harriet. Give us another biography of Harriet Tubman.”

Edda Fields-Black

Oxford University Press was the only publisher that understood her vision for the book. She was paired with Ted Bent, the executive editor of Oxford University Press’ trade division. Several weeks after she signed her contract, one of Bent’s other clients won the Pulitzer Prize for History. Fields-Black took it as a good omen.

“It was a book about slavery, so I felt I was in good hands,” she said referring to her partnership with Bent, who now has worked with two Pulitzer Prize-winning authors who have written about America’s original sin.

“He wasn’t trying to change what I wanted to do,” she said. “He could see its importance. He wanted to help me do it.”

The Pulitzer Prize, as prestigious as it is, is not a reward for the successful culmination of a great project about Harriet Tubman as far as Fields-Black is concerned. It is a recognition that much work has yet to be done that will involve a deeper exploration of slavery, revisiting the surprising paper trail of freedom in the form of pension records and the role the author’s wartime relatives played in the grand tableau of American resistance.

“I hope I’m changing the way we do research and the way we write about [slavery] and the way we even think about enslaved people,” she said.

In explaining a methodological approach that “opened a portal of the U.S. Civil War pension files which have previously been used by historians and genealogists mainly for individuals to reconstruct individual lives or couples,” Fields-Black described a eureka-level discovery that caused her to recalibrate her approach for the better.

Illustration of the Raid of Combahee River. Found originally within Harper’s Weekly Volume VII, no. 340, July 4, 1863. Public domain.

Illustration of the Raid of Combahee River. Found originally within Harper’s Weekly Volume VII, no. 340, July 4, 1863. Public domain.

One of her biggest insights working on “Combee” was a recognition that the testimonies of 90,000 U.S. Colored troop veterans contained in tens of thousands of pension files has been underutilized when it comes to reconstructing the nuances of African American community life during the last days of slavery, the Civil War and the post antebellum era.

The pension files had been used in individual genealogical searches for decades, but the largely untapped potential of the records to tell the larger story of the era came as a surprise to her.

Fields-Black was deeply moved by the accounts in the files and how they amplified the voices of men who shared both the mundane and outstanding details of their lives to justify their pension petitions. These were voices that are largely absent from Civil War narratives more obsessed with the minutia of battles and field maneuvers.

What emerged from these files, some as long as 250 pages and written in the elegant cursive handwriting of the era, is a stunning historical gold mine that causes the historian to shake her head in amazement just recalling it.

Fields-Black was data driven, but she always kept her mind open to tips and wise counsel from unexpected places in the hunt for narratives to make her decades-long fascination with various forms of rice cultivation from West Africa to the Gullah Geechee culture of South Carolina more accessible.

Serendipity in South Carolina

“My father is the last of his siblings to be born in Green Pond, S.C., which is a mile or two from where the [Combee] raid took place,” Fields-Black said. “My grandparents migrated first to Charleston, then to Miami, Florida, which is where I was born and raised.”

She began working on what she thought was going to be the history of the Gullah Geechee in 2013 or 2014 when the elements of what would eventually become her prize-winning book began to fall into place.

On top of her intensive research into the Gullah Geechee, she was also working on the libretto for “Unburied, Unmourned, Unmarked: Requiem for Rice” with the composer John Wineglass. She had also agreed to pull a comprehensive family history together — an ongoing project that could’ve been a full-time endeavor in itself.

“The Old Plantation,” South Carolina, about 1790. This famous painting shows Gullah slaves dancing and playing musical instruments derived from Africa. Public domain.

“The Old Plantation,” South Carolina, about 1790. This famous painting shows Gullah slaves dancing and playing musical instruments derived from Africa. Public domain.

When she was in Charleston for two speaking engagements separated by a weekend, she got the notion to work on some family history while in the area.

“Long story short, I ended up on a rice plantation looking for the graves of the Fields family,” she said.

The family patriarch had given her the name and location of the plantation but warned her that the graves were unmarked and the cemetery was “growed up,” a term she wasn’t familiar with at the time.

“Now, I’m a Miami girl, so what I thought was an unmarked grave was very different from what I found when I went out to this cemetery — and I didn’t know what ‘growed up’ meant,” she said. “I had some idea, but I didn’t know I was going into this wilderness, right? And that the Fields graves were just these depressions in the ground.”

With the help of a friend, she began looking for the Fields graves. It wasn’t long before they stumbled upon graves connected to her grandmother’s family.

“It’s this little patch of woods with some tombstones still standing, many missing and these depressions in the ground,” she said. But she saw something else that day that she never imagined she’d see during her years researching her family’s history.

“We found one of the graves of an ancestor on my grandmother’s side broken open and full of water,” she said. “And his skeletal remains were floating to the top, visible to the casual visitor. And this had a very significant impact on me, as you can imagine, for a long time.

“The plantation was owned by one of the slaveholding families whose papers I was studying, so I had this intellectual understanding of the area’s history — and then here is my ancestor swimming in his grave,” Fields-Black said shaking her head.

Still, it was the impetus she needed to find out as much as she could about the Fields family scattered in unmarked graves in the thicket of weeds, tree roots and untended grass surrounding her.

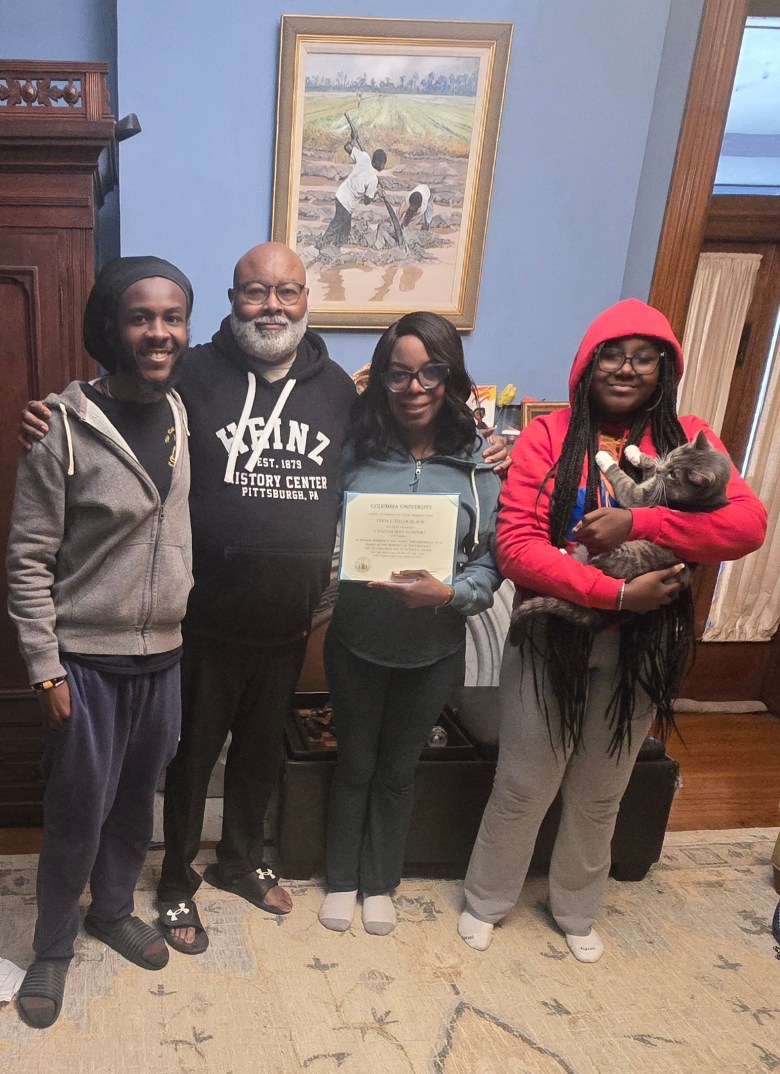

Edda Fields-Black at home with her husband, two kids and her Pulitzer proclamation. Photo courtesy of Edda Fields-Black.

Edda Fields-Black at home with her husband, two kids and her Pulitzer proclamation. Photo courtesy of Edda Fields-Black.

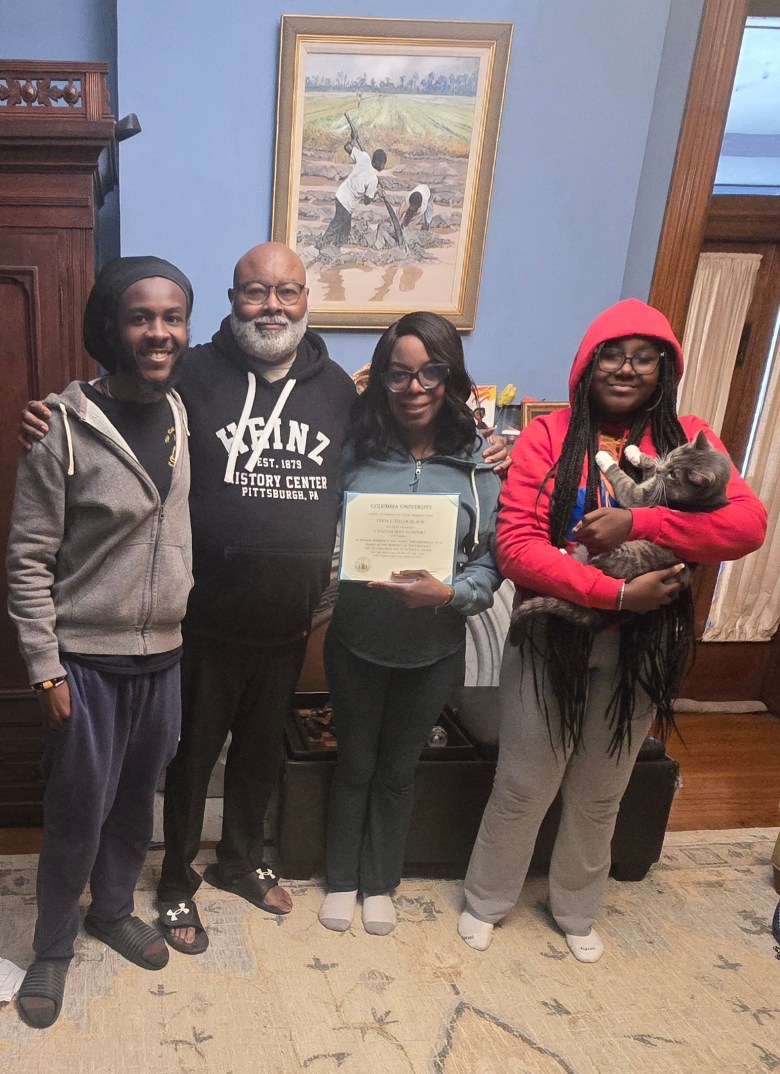

Historian and CMU professor Edda Fields-Black and her husband, historian, curator and archivist Samuel Black, director of African American programs at the Sen. John Heinz History Center. Photo of Edda and Sam at Columbia University’s Pulitzer ceremony. Photo courtesy of Edda Fields-Black.

Historian and CMU professor Edda Fields-Black and her husband, historian, curator and archivist Samuel Black, director of African American programs at the Sen. John Heinz History Center. Photo of Edda and Sam at Columbia University’s Pulitzer ceremony. Photo courtesy of Edda Fields-Black.

She turned to her friend and colleague Toni Carrier, a master genealogist who was the former director of Center for Family History at the International African American Museum.

She remembers pulling out photocopied records given to her by a cousin, the son of the family patriarch who is also doing research on the Fields family. The copies contained a census record that charted the lineage of descent from her great-great-great-grandfather down to her grandfather.

Something interesting happened when Fields-Black paid close attention to the files. Suddenly, she found details about the Combee raid previously unknown to her. She was able to confirm theories about two military companies that formed after the raid and some personal family history.

Hector Fields who fought alongside of Tubman was Edda Fields-Black’s great-great-great- grandfather. He was one of the men who eagerly joined the Union to fight for the freedom of his loved ones and those in his community who were still in bondage. Hector applied for a pension but never received it.

His brother, Jonas, was the author’s great-great-great-uncle. It is his pension file that contains much of the family history that forms the background of “Combee.”

The deeper Fields-Black dug into the pension files, the more accessible her family history became. Every new piece of information, whether confirming or debunking previous notions, enriched her family history and her own scholarship in the process.

“These 90,000-plus U.S. Colored soldiers and veterans and widows have millions of descendants — like me,” she said. Her greatest ambition is for millions of African Americans to be able to identify their enslaved ancestors.

Edda Fields-Black speaks during the Juneteenth Keynote Lecture on Tuesday, June 18, 2024. Photo courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University.

Edda Fields-Black speaks during the Juneteenth Keynote Lecture on Tuesday, June 18, 2024. Photo courtesy of Carnegie Mellon University.

“We, especially at this moment in time in the history of our country, should be able to tell our own story, to be able to write our own history as family members, as descendants and to pass it down to our children to teach in our churches, our lodges, our clubs, our Saturday schools, all of these things,” she said.

“And you know who you are and you know who you came from and you know what they went through, but you also know how they got over.”

Fields-Black has taught in the history department at CMU since 2000 and is currently director of the Humanities Center at the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences.

Balancing the responsibilities of being a prolific author of articles and books about the intersection of rice and race with those of wife, mother, teacher, institutional leader and librettist hasn’t been easy. She’s developed a talent for getting big and complicated things done.

For her next book, Fields-Black plans to meticulously research an estimated 500 to 700 pension files. “I’m going to start in the Gullah Geechee region,” she said. “I want to expand my scope beyond the Combee River. I want to write about slavery in the U.S. South from the pension files — from the perspective of the enslaved communities.”

“No, that doesn’t sound hard at all,” I said. Fields-Black laughed, as if ready for the challenge.