Philadelphia city agencies use a variety of so-called artificial intelligence tools for a range of tasks, ranging from writing software and giving parking tickets, to flying police drones and doing facial recognition for criminal investigations, officials say.

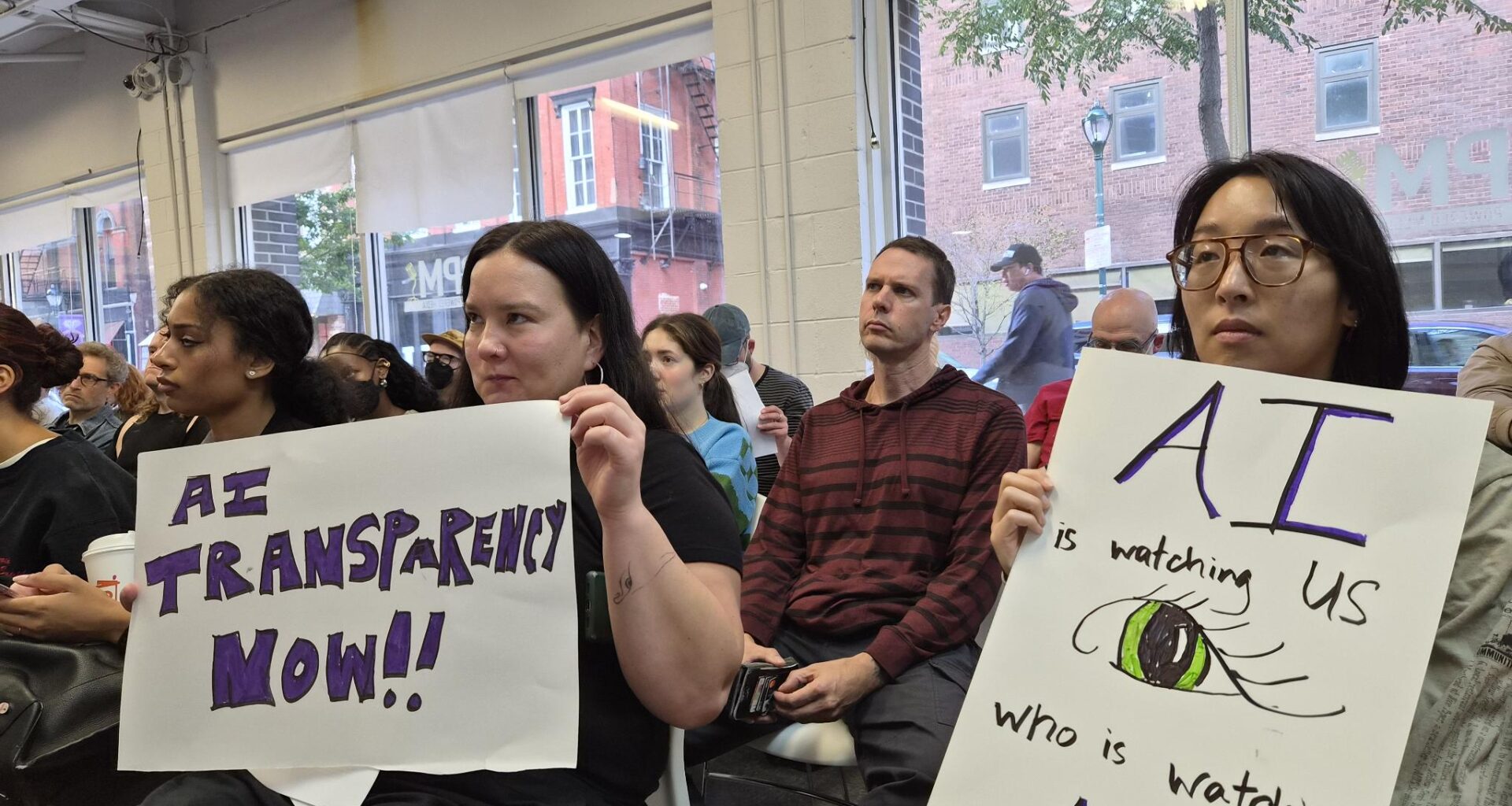

The profusion of such systems at city agencies was one of the takeaways from a City Council hearing Wednesday that explored the sprawling and potentially worrisome world of AI, and how the city is managing its burgeoning use both within and outside of government.

Much of the hearing focused on potential harms from AI systems that might leak confidential data, produce errors, encroach on civil rights, exhibit bias, facilitate discrimination, be used to target immigrants, or make sensitive decisions in areas like health care and policing without human input.

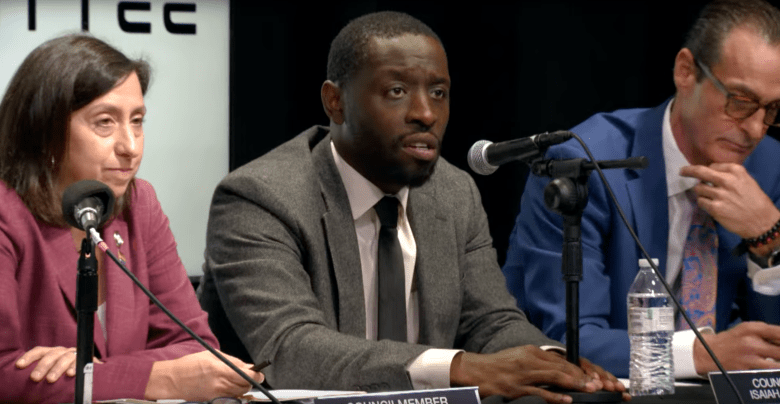

Councilmember Jim Harrity mentioned the Tom Cruise movie “Minority Report,” in which police arrest predicted murderers before they commit any crime, and said he was wary of giving up any freedoms in the name of safety. Councilmember Nicholas O’Rourke said it was up to cities like Philadelphia to individually make sure AI systems are used only in an ethical manner.

Philadelphia City Council held a hearing on artificial intelligence technology at PhillyCAM. Oct. 15, 2025. (Courtesy of PhillyCAM)

Philadelphia City Council held a hearing on artificial intelligence technology at PhillyCAM. Oct. 15, 2025. (Courtesy of PhillyCAM)

“We can’t rely anymore on Big Brother, the state, federal government, what have you. Localities, we have to look out for ourselves. We got to protect us,” he said during the hearing, which was held at PhillyCAM, a community media center and studio.

City officials testified that software programs labeled as artificial intelligence have already been used for years in ways that ultimately benefit residents. At the same time, some hearing attendees accused them of glossing over the police department’s embrace of AI and moving too slowly to institute protections against its misuse.

“This technology is moving very fast,” said Councilmember Rue Landau, an attorney and the hearing organizer. “We have a U.S. Supreme Court who doesn’t seem very set on enforcing the current laws that we have. It’s really up to us to make sure that we’re putting in the guardrails, to make sure that we’re not going to go years in the past of perpetuating discrimination, perpetuating inequities, and making sure that we’re taking care of people throughout Philadelphia.”

Looking for potholes, ticketing speeders

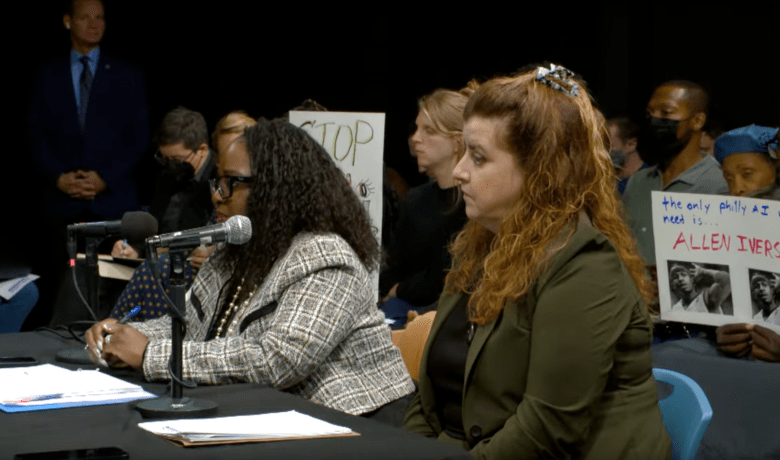

Melissa Scott, the city’s chief information officer in the Office of Innovation and Technology, said governments and companies have for decades used a class of AI systems called machine learning tools. They include software that can detect patterns, forecast demand for services, spot fraud, route 311 requests, find suspicious activity in computer security logs and improve search results.

What’s new in recent years is generative AI — systems that are trained on huge volumes of online text, pictures, and other media, and then can answer questions in plain English, create new images, or generate other content, Scott said.

City agencies use some generative tools, such as GitHub Copilot, which takes a user’s suggestions and creates software code; Microsoft’s Copilot, the AI function in that company’s word processing and other programs; Einstein GPT, which is used by Salesforce, a maker of 311 systems; and several others that Scott listed off during the hearing.

Philadelphia’s chief information officer Melissa Scott, left, and the mayor’s chief legal counsel Kristin Bray testified at a City Council hearing on artificial intelligence held at PhillyCAM. Oct. 15, 2025. (Courtesy of PhillyCAM)

Philadelphia’s chief information officer Melissa Scott, left, and the mayor’s chief legal counsel Kristin Bray testified at a City Council hearing on artificial intelligence held at PhillyCAM. Oct. 15, 2025. (Courtesy of PhillyCAM)

Landau said the Streets Department also uses an AI system to evaluate potholes and road obstructions, and the Philadelphia Parking Authority uses AI to issue tickets. Semi-automated ticketing systems in the city include red light cameras, speed cameras like those recently installed along Broad Street, and bus-mounted cameras targeting cars that block bus lanes.

Before a city agency starts using a product like Microsoft Copilot, Scott’s staff does a risk analysis to examine the data the system outputs, look for errors and biases, and make sure employees are trained to detect incorrect information, she said.

The city is also in the process of creating a training program on publicly accessible generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Google Gemini for city employees so they understand the need to protect city data, Scott said.

“Say you’re working on something for the city, and you go home and you’re working on it from home. I can’t stop you from uploading that information into Gemini, and then it goes out into the ecosystem of the world,” she said. “We have to train you and then hold individuals accountable, as far as letting them know that this is against the rules. You’re not allowed to upload city data into these online tools.”

The city will establish an interdepartmental Artificial Intelligence Governance committee early next year to review its policies, track evolving technology, work with experts, and make sure use of AI “remains aligned with our values, our legal obligations and the expectations of our residents and employees,” said Kristin Bray, chief legal counsel to Mayor Cherelle Parker and director of the Philly Stat 360 data dashboard.

Asked by Harrity and others if community members could have a role on the governance committee, Bray said discussions are under way about how to integrate the community, AI experts, and officials from other cities in the oversight process.

“The most advanced AI in the sky”

During the hearing, Scott said that to her knowledge, the city is not using AI in law enforcement. That was one of several comments that prompted criticism from local tech activists, who noted that the city has in fact used technologies like license-plate readers for years.

In addition, Scott and Bray failed to specify how the city checks for bias in technology procurement processes, and could not say who would serve on the governance committee, the activists said.

“The city’s non-answers today were shocking and disappointing,” said Devren Washington, organizing director at People’s Tech Project and founder of the Philly Tech Justice Coalition. “But the people spoke clearly: we want parks and libraries, schools and jobs, not black box AI that makes our lives worse while making billionaires richer.”

From left, Philadelphia City Council members Rue Landau, Isaiah Thomas, and Jimmy Harrity participated in a hearing on artificial intelligence technology held at PhillyCAM. Oct. 15, 2025. (Courtesy of PhillyCAM)

From left, Philadelphia City Council members Rue Landau, Isaiah Thomas, and Jimmy Harrity participated in a hearing on artificial intelligence technology held at PhillyCAM. Oct. 15, 2025. (Courtesy of PhillyCAM)

The Philadelphia Police Department subsequently confirmed that it does use AI systems and is considering deploying more of them. “The Police Department is part of a larger ecosystem in city government, and it adheres to a standard of practice for using technology and data integrity, as does every city agency and department,” PPD said, in a statement provided by the mayor’s office.

For example, the department uses AI-power facial recognition and image analysis for “limited, legally authorized investigations” through the state police Justice Network (JNET) and the Delaware Valley Intelligence Center, the statement said. A PPD directive “requires case-specific justification and supervisory approval, and prohibits general surveillance or crowd monitoring.”

The police operate 125 license-plate recognition cameras through security software provider Genetec, and have the ability to do plate recognition through most patrol vehicles via an Axon Fleet 3 system, although that is not yet active. “These systems use AI to identify license plates and match them against law enforcement databases. Their use is governed by departmental policy to ensure investigative integrity and data security,” the department said.

PPD also recently started flying Skydio X10 drones, which “use onboard AI to support autonomous flight functions such as obstacle avoidance, low-light navigation, precision landings, and pre-programmed flight paths.” The AI is “strictly limited to flight safety and navigation, and does not include facial recognition or identity-matching capabilities,” the deparment said. Drone missions are monitored by licensed pilots.

The maker of the Skydio X10 drone advertises it as being “piloted by the most advanced AI in the sky.”

In addition, police body-worn cameras have a built-in transcription feature that converts audio into text. Those transcripts are not used for any kind of predictive report writing or automated decision-making, per PPD.

The police department has been exploring AI systems for years, officials said. In 2013, for example, it tried out Hunchlab, “a predictive policing tool designed to forecast crime grids,” the statement said. No such systems are currently in use.

It’s currently evaluating a real-time language translation tool and an Axon Dedrone system to track unauthorized drones, but those are not being used for police operations. While the city is testing Microsoft Copilot’s generative AI in other departments, that system “does not have access to sensitive law enforcement systems or data,” the statement said. “PPD is in the early stages of evaluating AI tools and any future use will be subject to rigorous legal, ethical, and operational review.”

No collaboration with ICE AI, officials say

During the hearing, Bray deferred on answering a question about whether the city would participate in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s use of AI to identify and detain immigrants.

PPD subsequently confirmed that it does not collaborate with ICE, Homeland Security, “or any federal agency on AI initiatives related to immigration enforcement.”

The department also said it has not entered into any agreements or discussions with the Trump administration regarding AI-based anti-drone initiatives for World Cup security ahead of next summer’s soccer games taking place at Lincoln Financial Field.

Mayor Cherelle Parker has generally declined to directly answer questions about ICE’s mass deportation efforts, although officials have said Philadelphia’s status as a sanctuary or “welcoming” city that limits cooperation with federal immigration agencies has not changed since she took office.

Despite the city’s assurances that it will only use AI in appropriate and carefully vetted ways, experts on the technology noted at the hearing that other cities and counties have already tried to use such tools for mass surveillance and predictive policing. They urged City Council to put in strict guidelines guaranteeing public accountability, oversight, and protection of citizens’ basic rights, and to ban or decommission harmful AI.

“This is not an Orwellian fantasy. This is a civil and human rights crisis enabled by the rise of artificial intelligence,” said Clarence Okoh, a civil rights attorney at Georgetown Law and a senior attorney at the nonprofit TechTonic Justice. “The city of Philadelphia must meet this critical moment and set a new national standard by placing civil and human rights at the foundation of AI and digital policy.”