Eight thousand people’s homes, hundreds of businesses, and part of Pittsburgh’s cultural centerpiece were all lost in the 1950s.City government demolished much of the Lower Hill District 70 years ago to make room for the Civic Arena, the former home of the Pittsburgh Penguins.Carlos F. Peterson — now in his 70s — watched his neighborhood razed to rubble from the roof of his childhood Lower Hill home. “You could look back and see the bulldozers, the dust,” Peterson said. “I remember walking back home, and the dust in my doorway was thick, powdery, like baby powder.”Once a bustling neighborhood, the Lower Hill District saw Pittsburgh label hundreds of homes and businesses as “slums” — leveling them and displacing their residents. Since the Civic Arena’s 2012 demolition, the site has been filled with parking lots, serving events at PPG Paints Arena, the Penguins’ current home. The emptiness of the former neighborhood is a painful reminder for former residents like Peterson.”It was part of my growing up that got broken away, chipped away. Literally demolished,” Peterson said.In 2007, Pittsburgh signed an agreement with the Pittsburgh Penguins, giving the hockey team’s real estate arm the sole rights to redevelop the 28-acre Lower Hill site. The Penguins’ promise was to right some wrongs of the 1950s displacement with new projects to serve the community.The Penguins developed roughly seven of those 28 acres over 18 years, with projects like the First National Bank skyscraper and the new live music venue currently under construction. A portion of the revenue from concert tickets will go back to the Hill District. But in October, the Penguins let their development rights expire, leaving the vast majority of the Penguins’ projects and promises unfinished. Pittsburgh’s Action News 4 reached out to the Penguins for an interview. The organization instead provided a statement.”The Penguins remain committed to the vision for inclusive development in the Lower Hill and are proud of the meaningful progress achieved in recent years with community leaders despite challenging economic circumstances,” the statement said. “Following the expiration of the Option Agreement, the organization will stay engaged in the City’s plans for the area and continue to be a collaborative partner in advancing future development.” “The community absolutely has the right to be frustrated at the Pens and at all of us, to be quite frank, because there have been promises made, promises not necessarily kept,” said Pittsburgh City Council President Daniel Lavelle, who represents the Hill District. “I think made a lot of money off of a parking lot, and did not fulfill all the goals and objectives that we worked on and that we were working to fulfill.”For decades, Hill District residents and descendants of those who were displaced have grown frustrated with the lack of action, with the sea of parking lots serving as a stark contrast with the former vibrancy of the neighborhood. Besides the homes and businesses, the Lower Hill was also home to historic jazz clubs, which fueled the Hill District’s broader cultural scene — one that went into decline when the Lower Hill was destroyed.Saxophone player Tony Campbell grew up in the Hill District. He performs gigs in the Hill with his band, Jazz Surgery.Even though musicians like Campbell do what they can to keep the jazz scene alive, he says it’s nothing compared to what it once was. “It just, I hate to say gutted it, but it just … didn’t seem to exist ,” Campbell said. “It erased it.”Gesturing up Centre Avenue, Peterson reminisced about all the businesses that once lined the street.“There were stores all the way up through here. All that’s gone,” Peterson said. “That was part of the economic part of the neighborhood. It’s done.”With the Penguins’ development rights officially expired, the land reverts back into the hands of city government with the Urban Redevelopment Authority and the Sports and Exhibition Authority. Lavelle wants the Lower Hill to go back to serving the community it was taken from as soon as possible. “All the wrongs of the past cannot be righted. We have to acknowledge that. Every sin that happened will not be fixed in this one development,” Lavelle said. “But we certainly can do as much as possible to ensure that whatever development occurs, occurs in a way that is equitable, occurs in a way that is beneficial to Hill District residents, to the African American community, and to the city at large.”Many residents want development to start with housing. Lavelle thinks more people living in the Lower Hill will support the Hill District as a whole, bringing the local economy back and supporting businesses like a much-needed grocery store, which the neighborhood has lost two of in recent years. “For the survival of the greater Hill District community, that site needs to be developed,” Lavelle said. “That site not being redeveloped is also holding back the development of the Middle and Upper Hill Districts.”Lavelle is more optimistic now than he has ever been about the area’s future, and says shovels should be in the ground at the Lower Hill site within two years. But even with that growing hope for what’s next for the Lower Hill, Peterson hopes future generations will remember what once was — both the neighborhood and its demolition. Peterson, who designed the Freedom Corner memorial that overlooks the Lower Hill, uses art to come to terms with the loss he experienced as a young boy. In the basement art studio of his Avalon home, he sat drawing in one of his familiar sketchbooks.“You could call it a curse to have to be able to put that stuff on paper,” Peterson said. “You’re not just drawing a pretty picture. You’re drawing from memory, you’re drawing from experience. You’re drawing from whatever hurt and pain there was, even what joy there was.”He wants his art to serve as a reminder of the neighborhood’s history for decades to come.“I’m hoping that they see that … people with feelings lived there,” Peterson said. “That’s what I want people to understand. It’s for them to see.”

PITTSBURGH —

Eight thousand people’s homes, hundreds of businesses, and part of Pittsburgh’s cultural centerpiece were all lost in the 1950s.

City government demolished much of the Lower Hill District 70 years ago to make room for the Civic Arena, the former home of the Pittsburgh Penguins.

Carlos F. Peterson — now in his 70s — watched his neighborhood razed to rubble from the roof of his childhood Lower Hill home.

“You could look back and see the bulldozers, the dust,” Peterson said. “I remember walking [from school] back home, and the dust in my doorway was thick, powdery, like baby powder.”

Once a bustling neighborhood, the Lower Hill District saw Pittsburgh label hundreds of homes and businesses as “slums” — leveling them and displacing their residents.

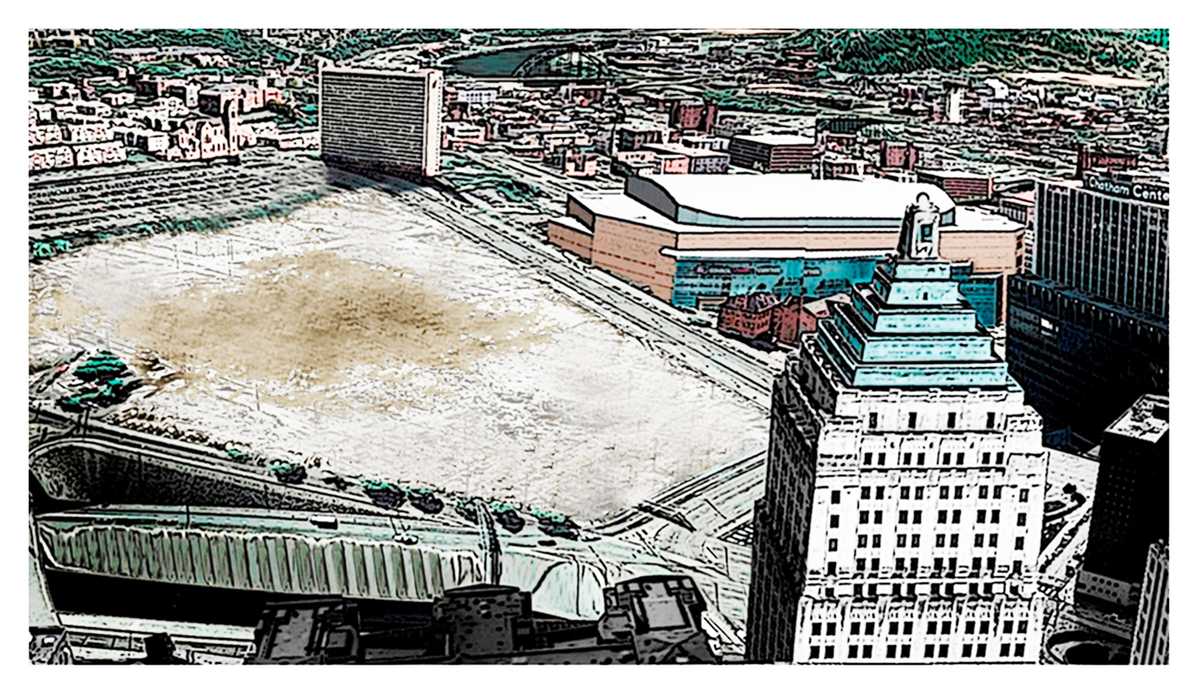

Since the Civic Arena’s 2012 demolition, the site has been filled with parking lots, serving events at PPG Paints Arena, the Penguins’ current home. The emptiness of the former neighborhood is a painful reminder for former residents like Peterson.

“It was part of my growing up that got broken away, chipped away. Literally demolished,” Peterson said.

In 2007, Pittsburgh signed an agreement with the Pittsburgh Penguins, giving the hockey team’s real estate arm the sole rights to redevelop the 28-acre Lower Hill site. The Penguins’ promise was to right some wrongs of the 1950s displacement with new projects to serve the community.

The Penguins developed roughly seven of those 28 acres over 18 years, with projects like the First National Bank skyscraper and the new live music venue currently under construction. A portion of the revenue from concert tickets will go back to the Hill District.

But in October, the Penguins let their development rights expire, leaving the vast majority of the Penguins’ projects and promises unfinished.

Pittsburgh’s Action News 4 reached out to the Penguins for an interview. The organization instead provided a statement.

“The Penguins remain committed to the vision for inclusive development in the Lower Hill and are proud of the meaningful progress achieved in recent years with community leaders despite challenging economic circumstances,” the statement said. “Following the expiration of the Option Agreement, the organization will stay engaged in the City’s plans for the area and continue to be a collaborative partner in advancing future development.”

“The community absolutely has the right to be frustrated at the Pens and at all of us, to be quite frank, because there have been promises made, promises not necessarily kept,” said Pittsburgh City Council President Daniel Lavelle, who represents the Hill District. “I think [the Penguins] made a lot of money off of a parking lot, and did not fulfill all the goals and objectives that we worked on and that we were working to fulfill.”

For decades, Hill District residents and descendants of those who were displaced have grown frustrated with the lack of action, with the sea of parking lots serving as a stark contrast with the former vibrancy of the neighborhood.

Besides the homes and businesses, the Lower Hill was also home to historic jazz clubs, which fueled the Hill District’s broader cultural scene — one that went into decline when the Lower Hill was destroyed.

Saxophone player Tony Campbell grew up in the Hill District. He performs gigs in the Hill with his band, Jazz Surgery.

Even though musicians like Campbell do what they can to keep the jazz scene alive, he says it’s nothing compared to what it once was.

“It just, I hate to say gutted it, but it just … didn’t seem to exist [anymore],” Campbell said. “It erased it.”

Gesturing up Centre Avenue, Peterson reminisced about all the businesses that once lined the street.

“There were stores all the way up through here. All that’s gone,” Peterson said. “That was part of the economic part of the neighborhood. It’s done.”

With the Penguins’ development rights officially expired, the land reverts back into the hands of city government with the Urban Redevelopment Authority and the Sports and Exhibition Authority.

Lavelle wants the Lower Hill to go back to serving the community it was taken from as soon as possible.

“All the wrongs of the past cannot be righted. We have to acknowledge that. Every sin that happened will not be fixed in this one development,” Lavelle said. “But we certainly can do as much as possible to ensure that whatever development occurs, occurs in a way that is equitable, occurs in a way that is beneficial to Hill District residents, to the African American community, and to the city at large.”

Many residents want development to start with housing. Lavelle thinks more people living in the Lower Hill will support the Hill District as a whole, bringing the local economy back and supporting businesses like a much-needed grocery store, which the neighborhood has lost two of in recent years.

“For the survival of the greater Hill District community, that site needs to be developed,” Lavelle said. “That site not being redeveloped is also holding back the development of the Middle and Upper Hill Districts.”

Lavelle is more optimistic now than he has ever been about the area’s future, and says shovels should be in the ground at the Lower Hill site within two years.

But even with that growing hope for what’s next for the Lower Hill, Peterson hopes future generations will remember what once was — both the neighborhood and its demolition.

Peterson, who designed the Freedom Corner memorial that overlooks the Lower Hill, uses art to come to terms with the loss he experienced as a young boy.

In the basement art studio of his Avalon home, he sat drawing in one of his familiar sketchbooks.

“You could call it a curse to have to be able to put that stuff on paper,” Peterson said. “You’re not just drawing a pretty picture. You’re drawing from memory, you’re drawing from experience. You’re drawing from whatever hurt and pain there was, even what joy there was.”

He wants his art to serve as a reminder of the neighborhood’s history for decades to come.

“I’m hoping that they [will] see that … people with feelings lived there,” Peterson said. “That’s what I want people to understand. It’s for them to see.”