Pittsburgh’s first-ever Vision Zero Summit sold out five days before taking place. Speakers said it was a sign of how far the Steel City has come since setting a goal in March 2024 of reducing deaths and injuries in traffic crashes to zero.

The city isn’t there yet — there were 21 crash fatalities in 2024 — but the city has made substantial progress, cutting vehicle collisions by 32% in 2024 compared to the 20-year average. The summit offered more granular insights into how Pittsburgh has accomplished this, showcasing projects that ranged from AI-assisted mapping of bike routes to the city’s nationally recognized efforts to install speed humps and bike lanes. The conference, co-hosted by the city and BikePGH, took place in the University Club on Pitt’s campus in Oakland.

Clark Haynes of velo.ai shows data collected on Strip District bike routes during the Vision Zero Summit on Oct. 17, 2025. Credit: Colin Williams / CP

Clark Haynes of velo.ai shows data collected on Strip District bike routes during the Vision Zero Summit on Oct. 17, 2025. Credit: Colin Williams / CP

Keynote speaker Claudia Adriazola-Steil of the World Resources Institute said Pittsburgh was ahead of much of the world in pursuing a concrete Vision Zero plan. She compared local efforts to those underway in other cities such as Oslo, Norway; Groningen in the Netherlands; and, closer to home, Arlington, Va.

“Pittsburgh has good bones,” Adriazola-Steil said. “I would say in Pittsburgh, the situation is not as severe as I have seen [elsewhere in] the world.”

Tracing Vision Zero’s origins in the Dutch Stop de kindermoord (“Stop murdering kids”) protests of the 1970s through the Swedish government’s 1997 Vision Zero campaign, Adriazola-Steil highlighted global examples mirroring local projects and future steps the city could take. Among the projects were boulevardization and speed humps along an arterial road in Bogotá, Colombia, Jersey City’s installation of more than 760 speed humps and 225 “No Turn on Red” signs, and Arlington’s use of bioswales to calm traffic and reduce risks to people inside and outside of vehicles. Adriazola-Steil also touted the economic benefits of traffic calming, bike lanes, and other Complete Streets infrastructure.

“The perception is business is going to go down if you don’t have a parking spot,” she said in response to a question from Pittsburgh City Paper concerning recent resistance to bike lane installation in the Strip District. “We have studies that show that is exactly the contrary because when it comes to bikes, they make small businesses thrive.”

She had Oslo had approached local resistance by first installing temporary bike lanes with business owners for a trial period, then making them permanent if business owners benefitted.

Other speakers were similarly bullish on green infrastructure and Complete Streets. Among the day’s panelists were City of Pittsburgh staffers, local elected officials, urban planners, and tech workers who discussed the ways local projects had improved roadway safety throughout the city and region.

Interestingly given the Penn Avenue bike lane controversy, many of the panels focused on infrastructure in and around the Strip. One example during a community engagement panel featured representatives of BikePGH, the Lawrenceville Corporation, and velo.ai spotlighted community discussions with Pittsburghers who supported and opposed bike lanes. velo’s approach included a detailed mapping of the Strip’s main bicycle corridors, including traffic hazards — their data showed the bike lanes along the Terminal Market on Smallman Street to be among the most dangerous for cyclists.

Elsewhere, Pittsburgh Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI) staff showed traffic analysis and renderings of a forthcoming Liberty Avenue safety project. City officials also told participants about municipal efforts to respond quickly to fatal crashes. It was all part, speakers said, of being a compassionate neighbor.

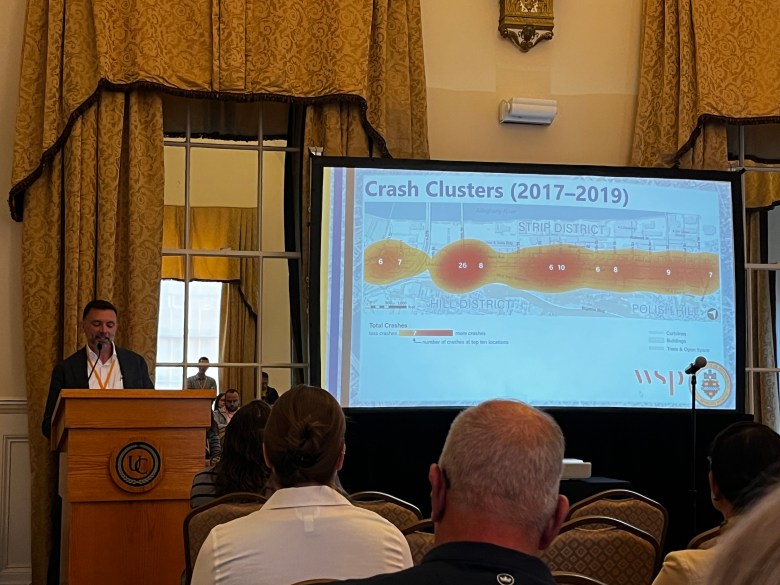

Mike O’Connor of global engineering firm WSP discusses Liberty Avenue improvements during the Vision Zero Summit on Oct. 17, 2025. Credit: Colin Williams / CP

Mike O’Connor of global engineering firm WSP discusses Liberty Avenue improvements during the Vision Zero Summit on Oct. 17, 2025. Credit: Colin Williams / CP

“Part of Vision Zero is the belief that all roadway fatalities are preventable,” DOMI assistant director Angie Martinez said. “I will add to that that all roadway fatalities are senseless. If you like me have lost a loved one in a crash, you know this to be painfully true.”

Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey said educating the public would be a key part of continuing DOMI’s work. The department will face budget constraints and lingering skepticism from some corners when Gainey’s probable successor Corey O’Connor takes over next year.

“Getting to zero [traffic fatalities], guess what it does — it makes our city more welcoming,” Gainey said. He said he hoped the city could get away from “the traditional thought that bridges divide instead of unify” and that neighborhoods could work across borders to improve safety.

“This is an education process that can talk about how we remove segregated neighborhoods, how we include everybody in neighborhoods, how we build neighborhoods, how we make them more safe, and what we’ve got to do to never see another child die,” he added.

RELATED