Checkpoint 300 and the lived reality of Palestinian Christians

The road to Bethlehem is closed.

Not metaphorically. Not spiritually. Literally closed — by checkpoints, separation walls, the infamous Checkpoint 300 and military orders that prevent Palestinian Christians from reaching the Church of the Nativity this Christmas. Evangelical Lutheran Pastor and Palestinian Munther Isaac has watched his congregations shrink as Christians flee occupation, violence, and economic suffocation. The city where Christ was born has become, in Isaac’s words, “an open-air prison.”

As Americans tell the story of Mary and Joseph journeying to Bethlehem, our Palestinian siblings are asking a pointed question: Will you make the journey to hear us?

The world has been watching Gaza burn for over two years. There have been over 1,000 Palestinians killed in the West Bank alone by Israeli forces and settlers — one of every five deaths a child. Even as a shaky ceasefire holds in Gaza, the West Bank experiences what the New York Times called “an acceleration” of this violence. This past October saw the highest number of documented settler attacks in the West Bank since the U.N. began tracking them in 2006. In one month, there was more than 260 attacks averaging eight a day — in the area which is only a little bigger than Rhode Island.

American churches – especially many of us in the Reformed tradition – bear some responsibility for the theology that has enabled this tragedy.

The heart of the Holy Land is being ripped apart. And the American churches – especially many of us in the Reformed tradition – bear some responsibility for the theology that has enabled this tragedy.

When theology becomes a weapon

In 2009, Palestinian Christian leaders issued the Kairos Document, a theological cry echoing that of the 1985 Kairos Document against apartheid, written by South African Christians. The Palestinian leaders wrote: “We ask our sister Churches not to offer a theological cover-up for the injustice we suffer, for the sin of the occupation imposed upon us.”

That plea largely went unheard in American circles; we were too busy managing our own controversies, too afraid of being labeled antisemitic, and too uncertain about how to parse the competing narratives. Meanwhile, the Palestinian Christian population has continued its precipitous decline — from 18% of Palestine in 1948 to less than 2% today.

We are compelled to come to grips with what our theological silence has wrought.

This Christmas, as we sing “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” we are compelled to come to grips with what our theological silence has wrought.

How Christian Zionism reshaped American biblical imagination

The crisis is fundamentally hermeneutical. How we read Scripture matters: not just for our own souls, but for the lives of people in the world. Over the past couple of years, I’ve encountered theology that uses Genesis 12:3 as a divine real estate deed for contemporary political purposes, theology that invokes Joshua’s conquest narratives to justify ethnic cleansing, theology that treats Palestinian lives as collateral damage in some sort of eschatological drama. When we think this way, we turn the gospel into, in the words of the Kairos Palestine document, “a weapon with which to slay the oppressed.”

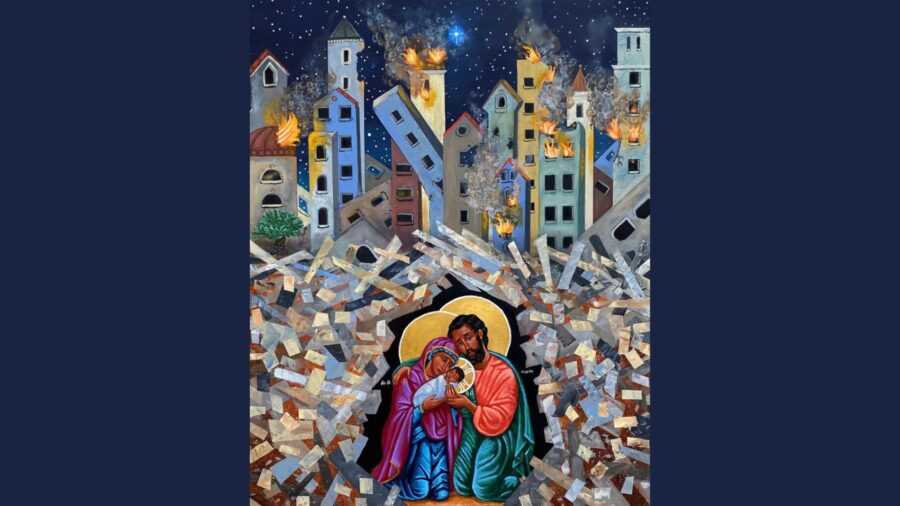

Photo by Munther Isaac @MuntherIsaac on X.

Photo by Munther Isaac @MuntherIsaac on X.

This is not a new problem. The Hosanna Preaching Project, hosted by the Palestinian Justice Network of the PC(USA), names the core theological error: “assertions that belonging to one or another religious or national community gives one’s life a value, a vocation and a unique relationship to God which somehow supersedes any of the others … easily leads to violence, abuse and oppression, as history all too clearly demonstrates.”

The theology used to justify and fund the displacement and occupation is not an academic exercise for Palestinian Christians. This is the real practice of harmful theology behind the bulldozers demolishing their homes, the biblical justification cited by settlers seizing their olive groves, and the American evangelical funding flowing to illegal settlement expansions.

Palestinian liberation theology

In response to this crisis, Palestinian Christians have developed one of the most important liberation theologies of our time. Yet most American pastors have never encountered it.

Palestinian Christians have developed one of the most important liberation theologies of our time. Yet most American pastors have never encountered it.

Naim Ateek: justice as the heart of the gospel

Palestinian liberation theology is best inaugurated by Naim Ateek, an Anglican priest expelled from his home in Beisan in 1948, in his seminal 1989 book Justice, and Only Justice. Ateek uses the prophet Jonah as his hermeneutical key — a story about God’s love extending even to Israel’s enemies, about divine grace which overrides ethnic boundaries. He argues that Christians must read Scripture from an “inclusivist” perspective, with Jesus as the supreme interpretive principle. A reading which negates human dignity or justifies oppression cannot be faithful to the gospel, no matter how many proof texts we imagine can be mustered in its favor.

Mitri Raheb: the decolonization of biblical theology

Another example is the “decolonizing” approach developed by Mitri Raheb, the founder of Bethlehem’s Dar al-Kalima University. In his book Decolonizing Palestine, published in 2022, Raheb shows how concepts such as “Israel,” “the land,” “election,” and “chosen people” have been weaponized in support of settler colonialism. He reads Scripture through the lens of empire and resistance, showing how Palestinian Christians’ experience under occupation reflects the Biblical witness of communities resisting Roman, Babylonian, and Egyptian empires.

Munther Isaa: holy stubbornness

Munther Isaac, perhaps the most prominent Palestinian Christian voice today, offers a theology that holds together lament and hope, cross and resurrection. His 2020 memoir The Other Side of the Wall is a must-read for any Presbyterian trying to understand Palestinian Christian experience. Isaac grew up during the First Intifada, lives behind the 9-meter separation wall, and leads a congregation that embodies what he calls “sumud“— steadfastness, perseverance, holy stubbornness in the face of erasure.

Lived theology

This year, Orbis Books published The Cross and the Olive Tree: Cultivating Palestinian Theology Amid Gaza, edited by John and Samuel Munayer. This volume of essays by eight Palestinian theologians represents what the editors refer to as “lived theology” — reflection forged in the crucible of survival and resistance. This is a theology written while bombs fall, while children die, while the world looks away.

These voices are not from the margins. … They are siblings and our family in Christ; their theological reflections merit serious attention by the American church.

These voices are not from the margins. They represent Christians who trace their lineage from the Pentecost event, and who have stood in witness in the land of Jesus for two millennia. They read Scripture in Arabic — the closest living language to Jesus’ Aramaic. They are siblings and our family in Christ; their theological reflections merit serious attention by the American church.

Gary Burge: an evangelical ally

Critically, Palestinian liberation theology has found allies among biblical scholars in the West. Gary Burge, an evangelical New Testament professor, has written extensively on how Jesus and the early church transformed “holy land” theology. In Jesus and the Land, Burge demonstrates that the New Testament universalizes and spiritualizes territorial promises, offering a theology where all places become potentially holy because of Christ’s presence. His work provides evangelicals a pathway out of Christian Zionism rooted in serious biblical scholarship.

Marc H. Ellis: a Jewish theology of liberation

Even Jewish liberation theologians have joined this conversation. Marc H. Ellis, who passed away in 2024, dedicated his career to arguing that post-Holocaust “Empire Judaism” has betrayed the prophetic tradition. In Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation, Ellis insisted that Jews cannot use past persecution to excuse present oppression — a message that cost him professionally but offered an essential prophetic witness.

These Western voices matter because they demonstrate that critiquing Israeli policy and challenging Christian Zionism is most certainly not antisemitism. It is, rather, a commitment to the prophetic tradition that demands justice regardless of who commits injustice.

The gap between General Assembly statements and congregational life

Our denomination has wrestled with Israel/Palestine for decades. The PC(USA) has passed numerous General Assembly resolutions, affirming Palestinian rights, supporting a two-state solution, and even, controversially, endorsing divestment from companies profiting from occupation. The Palestine Justice Network (previously the Israel/Palestine Mission Network) has provided education and advocacy resources.

The Israel/Palestine Mission Network of the PC(USA) renamed their organization the Palestine Justice Network of the PC(USA) in 2024.

The Israel/Palestine Mission Network of the PC(USA) renamed their organization the Palestine Justice Network of the PC(USA) in 2024.

Yet there remains a vast gap between denominational resolutions and congregational engagement. Most Presbyterian pulpits remain silent on Palestinian suffering. Most study groups avoid the topic. Most mission trips to the Holy Land engage Palestinian Christians only superficially, if at all.

Why? Why can we look away at the very land that is the center of our faith?

I know fear plays a part: fear of conflict, of being misunderstood, of giving pain to Jewish friends and neighbors. There’s ignorance, too. Many of my pastoral colleagues simply don’t know the history, don’t understand the theology, or lack the frameworks to navigate the conversation.

Why? Why can we look away at the very land that is the center of our faith?

But perhaps the deepest reason is theological: American Christianity has been so shaped by Christian Zionism that we cannot imagine faithfulness looking any other way. We have confused support for Israeli government policy with support for Jewish people. We have accepted a false binary: either you support Israel unquestioningly, or you’re antisemitic.

Palestinian liberation theology represents a third way: a way that takes seriously the horrors of the Holocaust and the Nakba’s catastrophe, that affirms Jewish dignity while defending Palestinian rights, and a way that seeks a future where no one is forgotten and dismissed in the world.

American Christianity has been so shaped by Christian Zionism that we cannot imagine faithfulness looking any other way.

As we light the candles and sing carols this Christmas, I invite us to sit with a haunting question: What does it mean to celebrate Christ’s birth while remaining silent about the suffering in his birthplace?

That is a question Munther Isaac asked during his devastating Christmas 2023 sermon, “Christ in the Rubble,” which he preached while Gaza was being destroyed: “If Christ were to be born today, would he not be born under the rubble in Gaza?”

Following Jesus beyond safe and sentimental faith

All people, churches, organizations, etc. are warmly welcomed and encouraged to share the digital version of Kelly Latimore’s “Christ in the Rubble” on social media and on their website, particularly during the Christmas season. You can find it here: https://www.redletterchristians.org/gaza/

All people, churches, organizations, etc. are warmly welcomed and encouraged to share the digital version of Kelly Latimore’s “Christ in the Rubble” on social media and on their website, particularly during the Christmas season. You can find it here: https://www.redletterchristians.org/gaza/

The question cuts deep for us American Presbyterians, formed as we have been by privilege and distance. We perhaps would rather have our Christmas tidy, sentimental, and safe. We like our nativity scenes without a refugee crisis, our Bethlehem without walls, and of course our Emmanuel without the mess of human tragedy.

But the Incarnation was never safe. God entered history on the margins, among the oppressed, under empire. The Word became flesh in a particular time and place, taking sides with the vulnerable. It was the shepherds, not Herod’s gilded court, who received the angels’ announcement of good news. The proclamation was in the roughness of the wilderness, not the comfort of the ballroom.

Palestinian liberation theology calls us to return to this scandalous particularity. It reminds us that Jesus was a Palestinian Jew, born under occupation, who lived as a religious and political minority, who challenged empire and paid the price. To follow this Jesus is to stand with today’s marginalized and to challenge today’s empires.

“If Christ were to be born today, would he not be born under the rubble in Gaza?”

At its best, the Presbyterian tradition has been prophetic. We have spoken truth to power, challenged injustice, sought reform when institutions failed their missions. We were abolitionists. We fought for civil rights. We divested from apartheid South Africa and from companies supporting Israel’s destruction of Palestinian homes. We have consistently said our loyalty to Jesus Christ transcends our loyalty to any nation, any policy, any comfortable arrangement.

Now we are facing a test of that commitment. Will we extend our prophetic witness to include Palestinian Christians? Will we challenge the Christian Zionism that dominates American evangelicalism and seeps into our own congregations? Will we make the journey to the other side of the wall?

By Samuel Smith – https://thisissamsmith.com/blog/travel/sketches-of-israelpalestine-checkpoint-300/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102147988

By Samuel Smith – https://thisissamsmith.com/blog/travel/sketches-of-israelpalestine-checkpoint-300/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=102147988

The road to Bethlehem is closed.

Palestinians are leaving the land in despair and in coffins. Soon, if current trends continue, there may be no Christian witness left in Jesus’ birthplace.

We can make our own journey to Bethlehem — not as tourists in search of a spiritual experience but as disciples desiring to follow Jesus toward all of those whom empire has rendered invisible. The shepherds made that journey long ago. They left their sheep and their familiar fields to seek the Christ child in a borrowed space. Mary and Joseph made the journey later too — refugees fleeing violence to Egypt, seeking sanctuary. Now it is our turn.

It isn’t clear how we can get to Bethlehem anymore. Still, the question is — will we make the journey anyway? God resides in the rubble of cities destroyed by hate and behind the walls built to keep people in.

This Christmas, will we join God there?