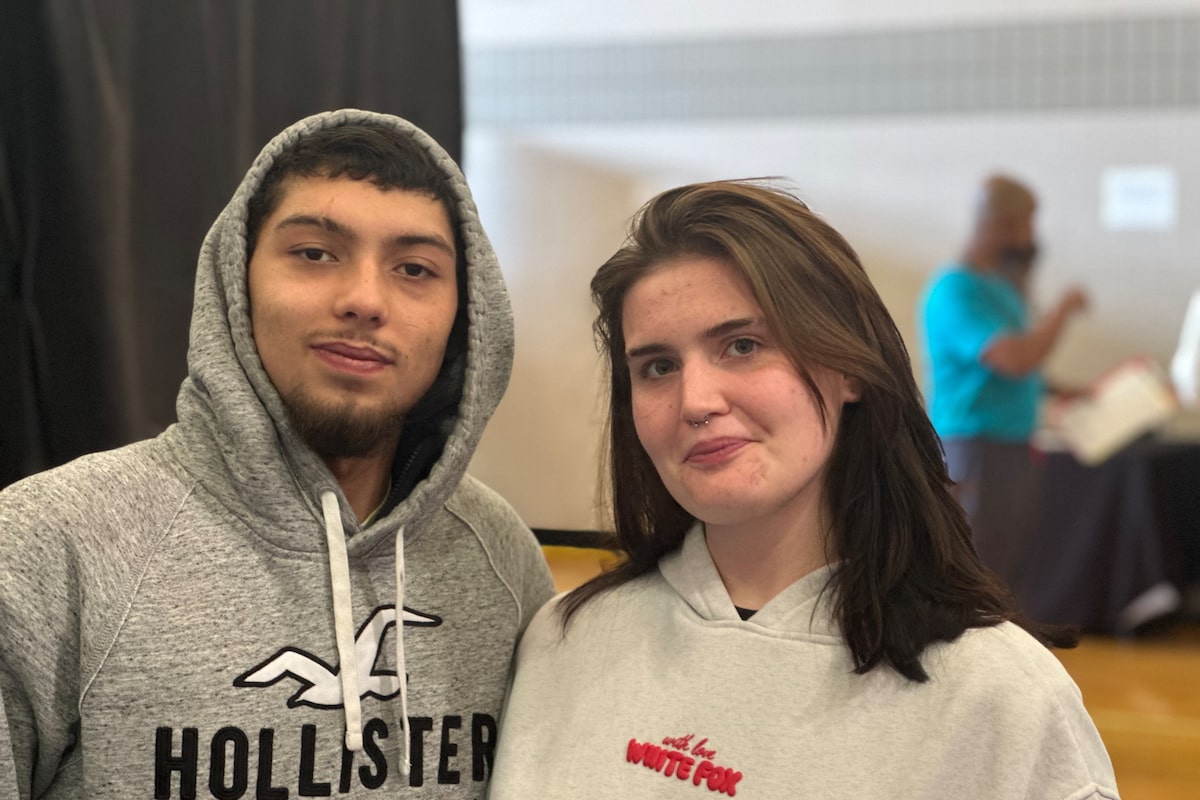

Giovanni Gonzalez, left, and Grace Frizzell, right, in Bethlehem, Pa., at a free clinic held by Remote Area Medical in a local high school, on Dec. 6.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

Giovanni Gonzalez has asthma severe enough that he wakes up in the middle of the night unable to breathe. He should be using an inhaler twice a day to keep the condition in check, but he can’t afford it. It would mean buying a US$300 maintenance puffer every 40 days, in addition to the US$200 emergency puffer he needs to stop sudden attacks.

A 20-year-old warehouse worker in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, he says it’s also not feasible to get health insurance on his wages. The cheapest plan he could find would cost US$240 a month in premiums, plus co-pays and deductibles. “I just have to suffer a little,” he said.

Mr. Gonzalez and his partner, Grace Frizzell, 21, were among the hundreds who came to a free pop-up medical clinic at a high school in Bethlehem, Pa., one December Saturday. The event was organized by Remote Area Medical, a non-profit that stages such clinics around the United States. They are rare opportunities for people without access to health care to see a doctor, dentist or optometrist free of charge.

The Commonwealth Fund, a health research group, estimates that 26 million Americans, or about 8 per cent of the population, have no health insurance. A further 23 per cent, or 75 million, are underinsured, meaning they have insurance but are discouraged from using it because they can’t afford the co-pays or deductibles.

The Remote Area Medical clinic where the dental component is set up.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

The problem is about to get significantly worse. President Donald Trump’s signature One Big Beautiful Bill Act cut nearly US$1-trillion from Medicaid, the government program that insures the lowest-income Americans, with the reduction scheduled to take effect next year. Republican congressional leaders, meanwhile, are blocking the extension of some Obamacare tax credits past the end of this year, which could lead premiums to more than double.

It all means that millions more Americans could soon find themselves in the same position as Mr. Gonzalez and Ms. Frizzell.

“It’s sad to see, especially when there are other countries with free health care. Instead of progressing and making it more accessible to people here in the U.S.–” Mr. Gonzalez said, before Ms. Frizzell finished the sentence: “The government is going to take it away.”

As debate rages in Washington, the uninsured and underinsured people visiting this free clinic in an 80,000-strong postindustrial town illustrate what it’s like to live without health coverage in the only high-income country that doesn’t guarantee it to all citizens.

Naida Simonetty makes too much money to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to afford a private plan.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

For Naida Simonetty, it has meant racking up thousands of dollars in hospital bills. Without insurance, the 58-year-old can’t get her chronic conditions – migraines and back pain – treated regularly. So she has landed in the emergency room when they’ve become debilitating.

Her most recent hospital visit was last month. She had a migraine so bad, her vision went blurry, she became dizzy, began vomiting and was in intense pain. The bill came to US$4,000, which she will slowly pay off in instalments. Doctors prescribed her two medications, but with price tags of US$600 and US$350, she opted not to fill the scripts. She left the pharmacy with a bottle of Advil.

“I’ve been working all my life, and when I ask for help, I don’t get it. I’m paying taxes and working hard,” said Ms. Simonetty, who works in the cafeteria kitchen of the high school that hosted the clinic. It’s a part-time job, so her employer doesn’t provide health insurance.

Her financial predicament is a common one: She makes too much money to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to afford a private plan. “Does the government want people to stay home doing nothing?” she asked as she sat on a collapsible chair, waiting to see one of the volunteer doctors working out of makeshift examination rooms constructed with black curtains.

Four Republicans join Democrats to force House vote on extending health care subsidies

Patricia Laws, 58, is in a similar situation. Her job as a parcel delivery driver doesn’t provide insurance or pay enough to buy a private policy. But she says her Medicaid application was turned down because she makes too much money.

“They said my income is too high. I’m like, ‘Yeah, so is my rent,’” she said while waiting in the bleachers of the school gym, where dentists and hygienists at more than a dozen work stations under white tents cleaned teeth, filled cavities and performed extractions.

When Ms. Laws suffered an attack of gastritis six years ago, she had no option but to go to the emergency room, which resulted in a US$10,000 bill. “It’s making my credit bad,” she said.

For others, there’s no choice but to skip medical procedures altogether.

Rafaella Chavez, 32, and Bruno Fernandez, 44, would like to get a comprehensive brain scan for their six-year-old son, who has cerebral palsy. But it would cost US$8,000, money that he, a carpenter, and she, a stay-at-home mother, don’t have.

Rafaella Chavez, left, and Bruno Fernandez, with their sons, ages six and one, at the Remote Area Medical clinic.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

The couple emigrated from Brazil in search of a higher standard of living. But not everything in the U.S. is as accessible as they had hoped. “The treatment here is very good, but the problem is that finding it is very difficult,” Ms. Chavez said as Mr. Fernandez played with their six-year-old and one-year-old sons.

On this day, they came to the clinic to see one of the optometrists set up on the stage of the school auditorium.

The barrier-free care provided by Remote Area Medical – the group treats people on a first-come-first-served basis and doesn’t require identification – is clearly needed. Every year, tens of thousands of people use its services at these rotating clinics across the country.

William Perry, 50, an emergency-room physician who regularly volunteers his spare time at free clinics such as this, knows that with health care cuts on the way, the need will only grow.

“The same way we have the police protect everyone, firefighters protect everyone, if there was a way we could have universal coverage where everybody can go to the doctor and they’re taken care of, just like in other countries, I would like that,” he said during a break between seeing patients. “It’s not like the police can say ‘we don’t cover you.’”

Dr. William Perry regularly volunteers his spare time at free clinics.Adrian Morrow/The Globe and Mail

Such prospects of reform seem remote. Many of the people The Globe and Mail met in Bethlehem said they did not vote at all in the 2024 election, doubtful that either party would do anything to improve their lives.

“I’m about over it. It doesn’t matter. They say your vote counts, but they’ve already got it figured out,” said Rob Humphrey, a 39-year-old construction worker. “The top one per cent needs to pay for everything, and we all need to have free medical.”

Mr. Gonzalez and Ms. Frizzell, meanwhile, said they didn’t vote because they were too busy working.

Her job at the parts counter of a car dealership offers a health care plan, but the premiums are more than US$400 a month, she says, and she wouldn’t be allowed to add Mr. Gonzalez to it. She has acid reflux but can’t afford to fill the prescription for medication to control it. Rent, utilities, car insurance and groceries take priority.

“Do I put a roof over my head or pay for health care?” Ms. Frizzell said. “It’s an uphill battle.”