Monongahela rye was produced in southwestern Pennsylvania along the Monongahela River and its tributaries. The style, which historically was often produced using three-chamber stills, is notable for its rye and malted barley ingredients, and a sweet mash process as opposed to a sour mash. The result is a drink with a rich and full-bodied flavor profile.

In 1892, the Pittsburgh Dispatch described the Monongahela Valley as the “Mecca of Distillers.” A few years later in 1899, the Ligonier Echo informed readers that there was no other place in the world from which “as much whiskey is shipped in one week as is sent out of Western Pennsylvania.”

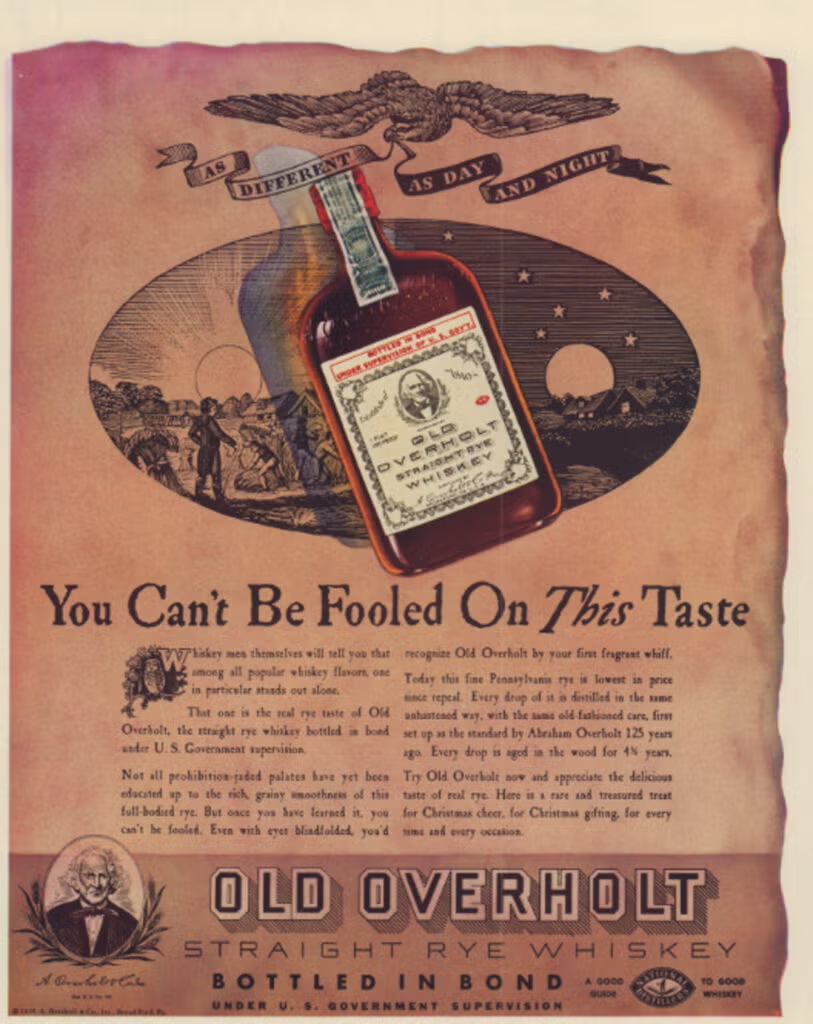

Among Pennsylvania’s popular distilleries were Samuel Thompson, which, according to family legend, was won in a poker game — or because of a debt by other accounts — and Gibson’s distillery, then one of the most prominent whiskey distilleries along with Old Overholt.

There was also Phillip Hamburger’s distillery, which produced Old Bridgeport. In a 1914 article for a trade publication, Hamburger’s business partner Albert Hanauer romanticized what he described as “a nectar fit for the gods.”

By the 1820s, the Overholt family’s distillery produced 12 to 15 gallons of rye whiskey a day. (Courtesy of West Overton Village & Museum)

By the 1820s, the Overholt family’s distillery produced 12 to 15 gallons of rye whiskey a day. (Courtesy of West Overton Village & Museum)

“Inhale its exquisite aroma; enjoy its superb bouquet; it brings to the mind’s eye the smiling rye fields, the rye waving joyously in the sun, and the troop of happy children passing through,” Hanauer wrote. “Look again, and the liquid amber, coupled with the word Monongahela, bring remembrances of George Washington and the stirring days of the whisky insurrection.”

But prohibition halted production, and distilleries closed down. Their equipment was removed and sold for scrap value, and many of the buildings began to decay.

The rye whiskey industry in Pennsylvania could not survive the impacts of prohibition. Laura Fields partly attributes this to significant consolidation efforts that shut out independent distillers, a lack of corporate support and an inability to protect assets. Some local distillers also died by the end of prohibition, and there were no apprenticeships during that time, she said.

Only a few distilleries reopened in Pennsylvania after prohibition ended, Komlenic said.

“We did this to protect our families. Women were being beaten by their drunken husbands. Women were a huge factor in prohibition, as was the Methodist Church,” he said. “They all had lofty goals in mind, but they did not realize the draw of an illicit product.”

Michter’s was the last remaining Pennsylvania distillery until it closed in 1990. A print image of the distillery now hangs above a cabinet in Komlenic’s home office.